The current trajectory of Africa’s economies will be informed by three main factors: the debt crisis, great power competition, and climate change. Debt pressures will dominate in the short to medium term, while global warming and great power competition will inform the long-term economic welfare of the continent. This article will highlight how the combination of these dynamics is informing Africa-China economic engagement and how it will evolve going forward. As usual, the specific articulation of Africa-China economic engagement in individual African countries differs, often informed by the economic and fiscal strength of the country, the perceived strategic importance of countries to different actors, and the specific impacts of climate change and great power competition on local economies.

African public debt: The limited but important role of China

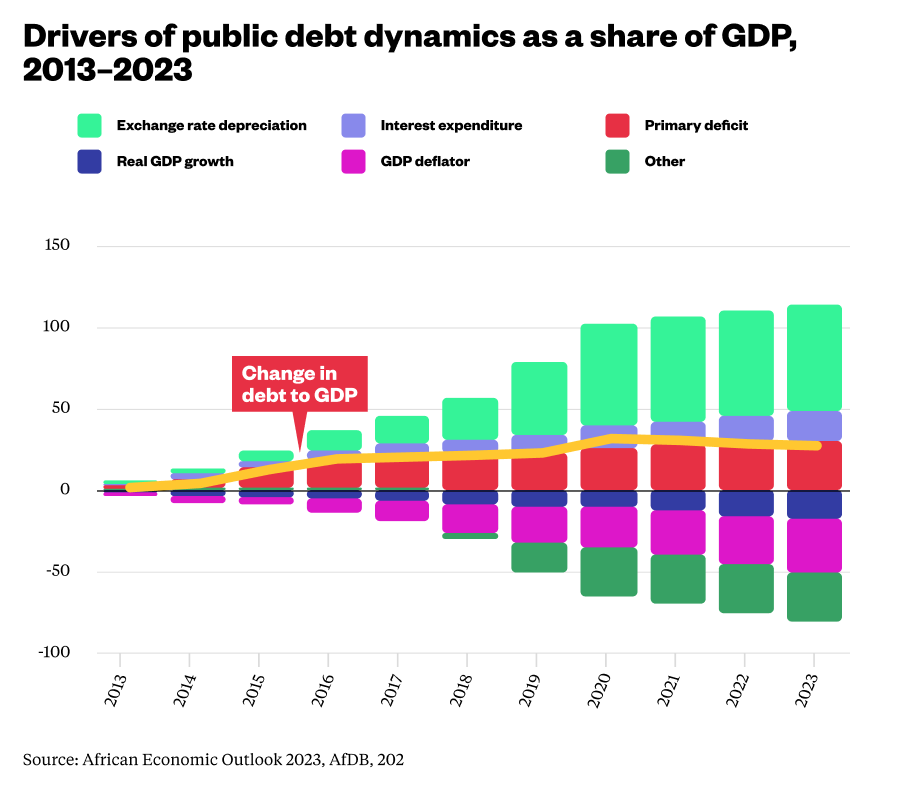

The debt burden, cost of capital, and exchange rate depreciation are the three variables causing fiscal headaches in African capitals. Africa’s public debt is the highest in decades, sitting at 56% to 65% of GDP, and is expected to increase. Nineteen of the region’s 35 low-income countries are already in, or will soon face, debt distress.

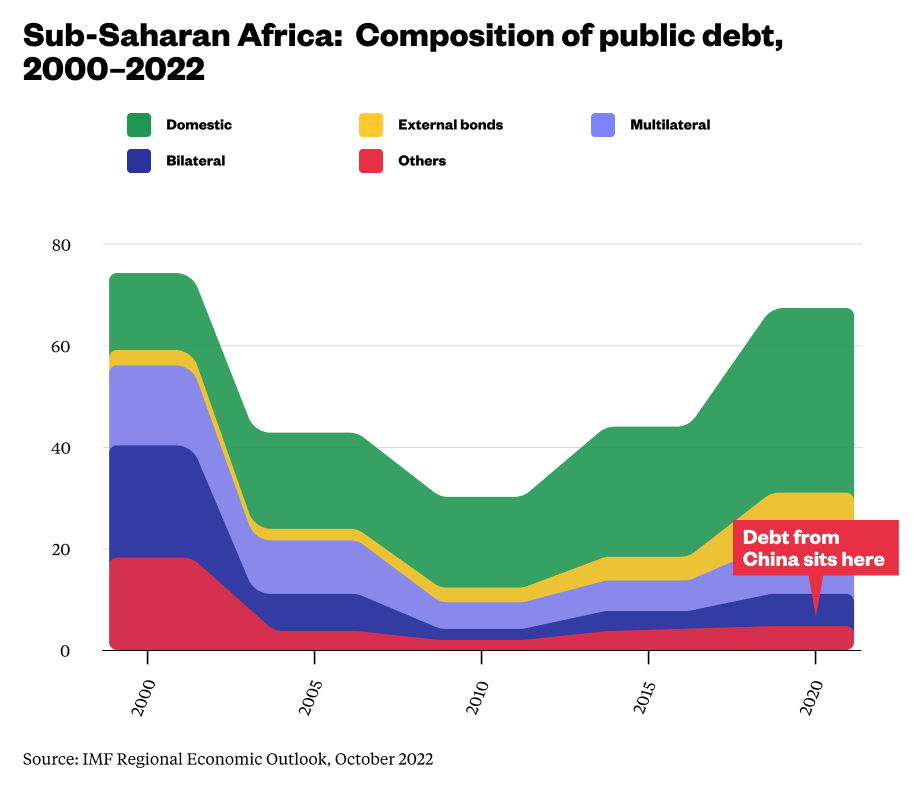

But contrary to popular belief, Africa’s debt has been mostly funded by a growing pool of private creditors — not China.

Over 20 years, African governments have replaced low-cost, long-term multilateral debt with higher-cost private funds. This has led to rising debt-service costs and higher rollover risks. Sadly, African currencies have depreciated against the U.S. dollar by 8% on average since January 2022, with some depreciating by more than 45%, giving exchange rate depreciation an outsize impact on external debt dynamics.

Composition of Chinese debt and lenders to Africa

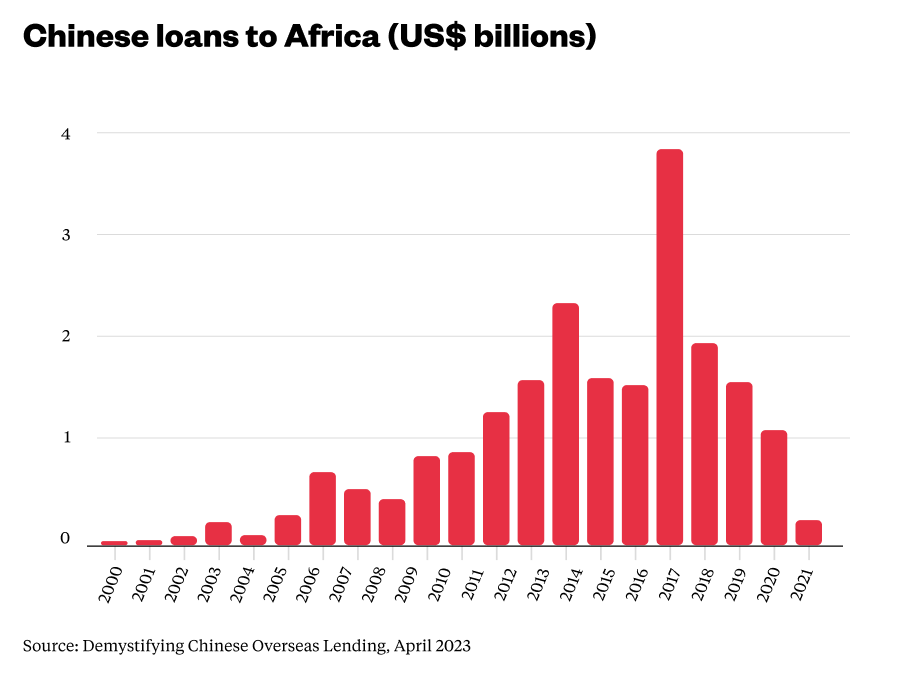

Loans from China make up just 12% of Africa’s total debt, financed mainly by the China Eximbank, the China Development Bank (CDB), the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), and Bank of China (BOC). China Eximbank has been the largest creditor since 2000 but Chinese financing has been growing increasingly commercial since 2015, although this has been in the context of declining lending from China.

Lending from China to Africa has been on the decline since 2016. Between 2000 and 2019, Chinese financiers committed $153 billion to African governments and state-owned enterprises. 80% of this was committed in 2010-2019. From 2019 onwards Chinese financiers committed only$7 billion to African borrowers, down sharply from its peak of $28 billion in 2016.

China’s declining lending is not unique to Africa, and is driven by a number of factors including:

- The consolidation of past investments;

- Slowing economic growth at home;

- An increased focus on domestic development;

- Growing interest in lending through multilateral bodies;

- Adoption of the “small is beautiful” approach in Chinese economic engagement;

- Shifts in the composition of the Chinese actors involved in outward expansion, including a more prominent role of the Chinese private sector in Africa;

- An awareness of and concern with the rapidly growing debt obligations of African (and other) governments.

China and debt relief in Africa

In the spirit of adept Chinese economic statecraft, the Chinese government has taken steps to demonstrate sensitivity to Africa’s debt position through debt relief measures. During the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), whereas Chinese creditors accounted for only 30% of all claims, they contributed 63% of debt service suspensions. Sixteen African countries benefited. Between 2000 and 2019, China canceled at least $3.4 billion of debt in Africa. In 2021, China signed debt relief agreements with 19 African countries and in 2022 announced that it would waive 23 unspecified interest-free loans with maturity by the end of 2021.

While some may dismiss these actions as symbolic gestures without any substantive impact, they demonstrate a source of power in China’s approach to Africa’s fiscal and debt pressures: responsiveness and flexibility. Chinese state financiers adapt to changing economic and political conditions in Africa, learn from experience with borrowers, and generally shift away from countries in deep fiscal and debt trouble towards borrowers with stronger economies and debt management.

The Triple Threat: Great power competition, the climate change emergency, and the debt crisis

The debt crisis in Africa is being reticulated through the dynamics of great power competition and climate change. Bickering between the U.S. and China has already crept into the general discourse on Africa’s debt crisis and into conversations and negotiations for countries like Zambia and Ghana. At the same time, climate change has been hammering Africa’s economic and fiscal welfare for decades. Climate change could lower the continent’s GDP by up to 3% by 2050 and has reduced economic output and growth in Africa more than in other regions.

Global warming negatively affects activity and revenue generation from key sectors such as agriculture, water, aquaculture, forestry, and tourism. Additionally, African countries are already spending 2-9% of their budgets in unplanned allocations to respond to extreme weather events. This has negative impacts on debt sustainability not only because funds earmarked for debt servicing need to be redirected to address climate emergencies, but also because climate events are a drag on revenues needed to pay off debt owed to creditors such as China.

Links between global warming and the Belt and Road Initiative

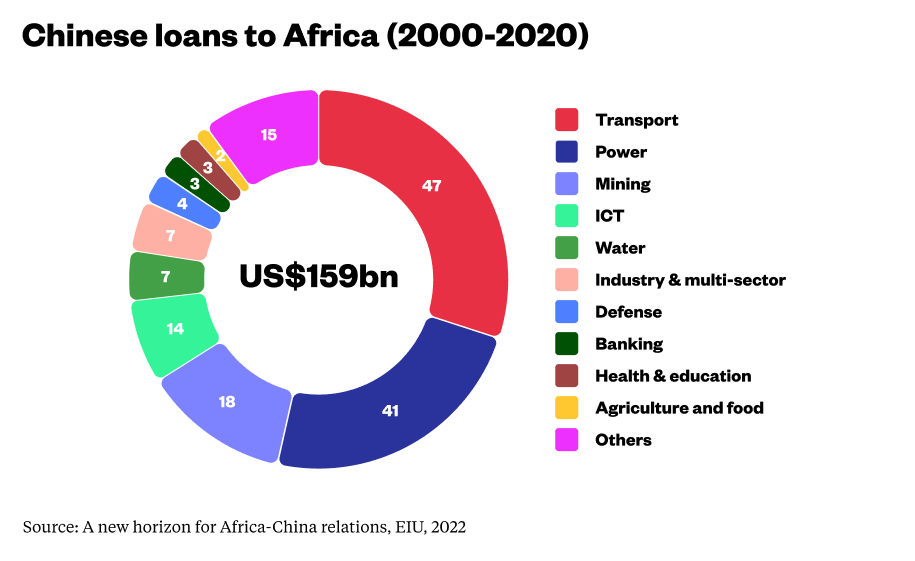

China’s state financing has long focused on infrastructure, and 43 African countries are countries with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) agreements — the highest number in any continent. Between 2000 and 2019, China committed $153 billion to African public-sector borrowers, and at least 80% of those loans went toward transportation, power, telecoms, and water.

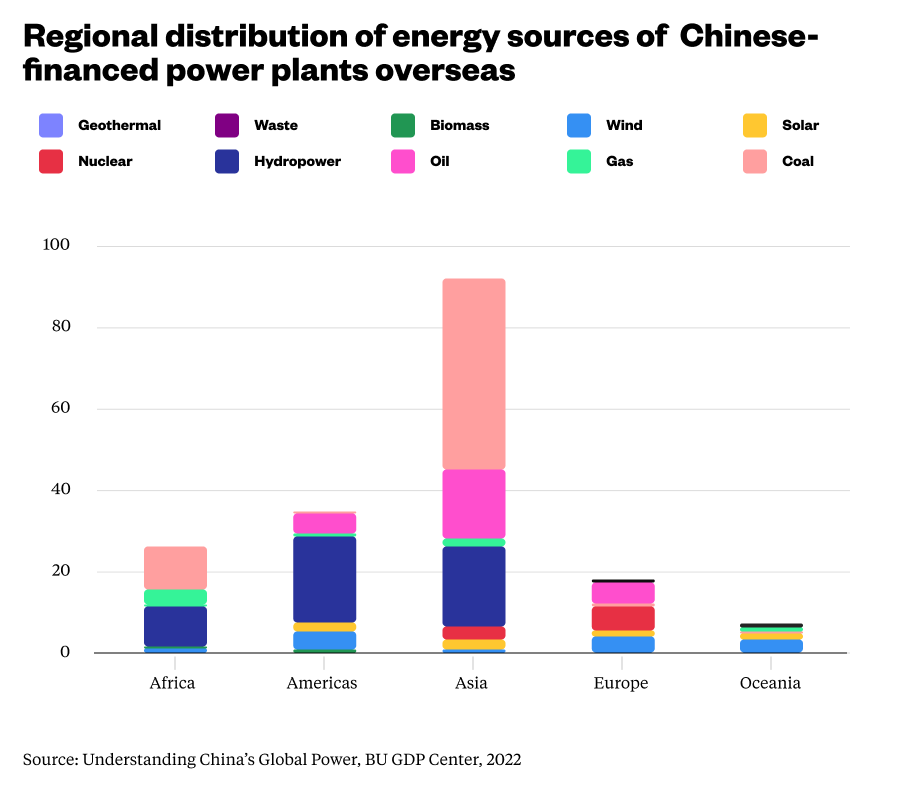

At the same time, eight of the 20 countries with the highest expected annual climate-related damage to road and rail assets relative to GDP are in Africa. Beijing should be particularly concerned about hydropower investments given that most Chinese-financed power plants in Africa are in hydropower (60%). In the driest climate scenarios, hydropower revenues could be 7% to 58% lower in key water basins in Africa. Climate-related damage to and interference with infrastructure not only hampers the multiplier effects of infrastructure investment, but also compromises the productive potential of debt, putting millions of dollars — much of it financed by China — at risk.

Beijing has signalled its pivot to greening the BRI through high-level guidance notes and policies and principles. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, of which China is the largest shareholder) has begun incorporating climate resilience into its road projects. But what is not clear is:

- Is existing BRI infrastructure in Africa climate-resilient and designed to withstand current and future strikes from climate change?

- Have African and Chinese governments integrated climate-related insurance into their infrastructure deals?

- Have the potential impacts of climate change been integrated into financial modeling regarding project viability and/or debt servicing linked to BRI loans?

One suspects that if any of the climate considerations listed above were in fact used, it was done so in a limited and haphazard way, exposing billions of dollars of infrastructure deals between China and African governments to the ravages of climate change. When it comes to African debt, the ability of BRI infrastructure to withstand the effects of climate change is more important than its environmental and climate footprint.

Africa-China relations in the new era of green diplomacy and competition

Within the milieu of Africa’s debt crisis, great power competition, and climate change, green diplomacy is forming the core focus of not only domestic but also foreign policy strategies for China, the U.S., and Europe. And here China is already leading. China is the largest investor in Africa’s power sector and most Chinese-financed power plant units in Africa are in clean energy. While policy bank investments have supported a large amount of fossil energy, the combination of Chinese policy banks and FDI investments are dominated by hydropower (60%), followed by gas (17%), coal (9%) then solar and wind (8%).

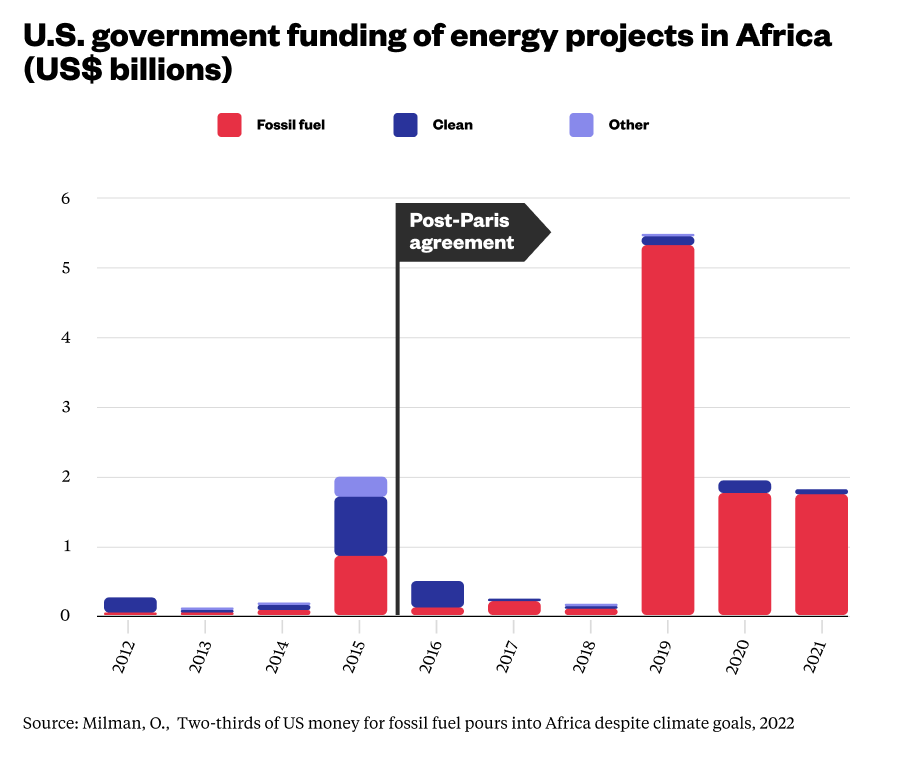

This contrasts sharply with the U.S. government’s energy portfolio in Africa, which is dominated by fossil fuels. Since 2015, the U.S. government has channeled more than $9 billion into oil and gas projects, and a mere $682 million to clean energy such as wind and solar.

So despite a great deal of green rhetoric out of Washington of a commitment to support “a just energy transition in Africa,” it’s clear where the money has been going. And while the G7’s Build Back Better World was specifically created to provide (among other things) a “climate-friendly” alternative to China’s BRI, it seems the U.S. and European governments do not have a track record of delivering this in Africa, and certainly not at the scale of China. If what the Dutch Trade Minister recently stated about Europe’s own green transition being impossible without China is true, then what about Europe’s green push in Africa?

China’s dominance in metals and minerals for clean energy

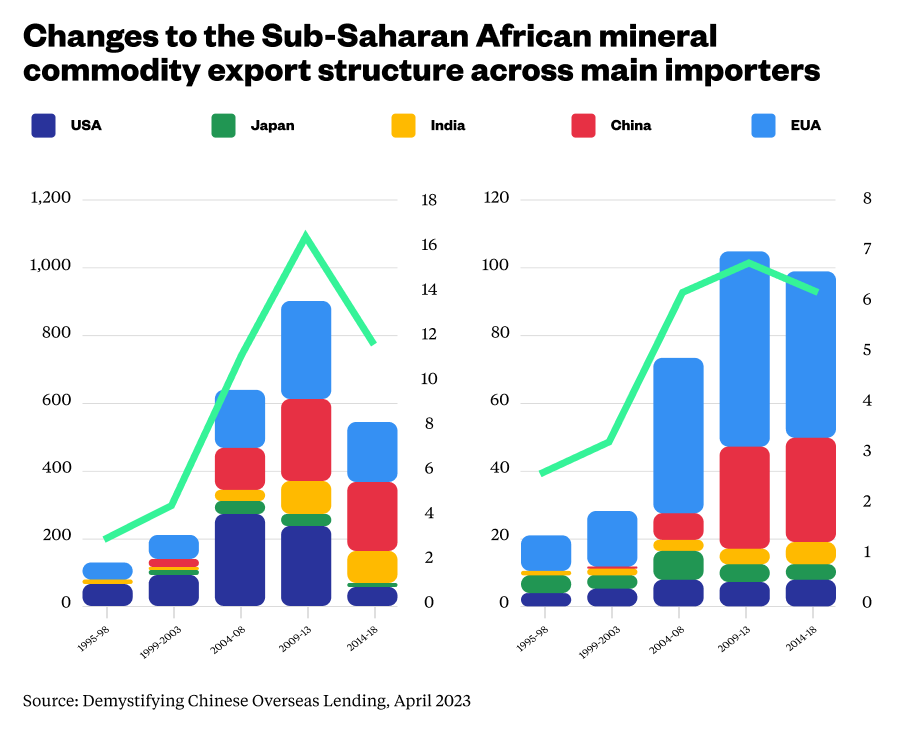

The transition from fossil fuels to clean energy will create demand for minerals and metals. Lithium, cobalt, and vanadium are critical for energy storage, and copper, indium, selenium, and neodymium are essential for manufacturing wind and solar power generators. China refines 68% of nickel globally, 40% of copper, 59% of lithium, and 73% of cobalt. It holds 78% of the world’s cell manufacturing capacity for EV batteries and hosts 75% of the world’s lithium-ion battery mega-factories. Africa will feel the pinch of competition for minerals particularly given resource abundance in Africa is increasing, not declining.

Africa hosts 59% of the world’s platinum group elements, as well as high percentages of known diamonds (48%), cobalt (75%), manganese (68%), and graphite (59%). Africa also has undeveloped resources of lithium. With its diverse and evolving mineral export markets, Africa will undoubtedly be affected by increasing geopolitical tensions between the U.S., Europe, and China. This will likely intensify the competition for world-class deposits in Africa, not unlike what we’ve already seen in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which accounts for 70% of global cobalt supply.

Control, hubris, and multipolarity

Going forward, we can expect African governments to make efforts to control metal and mineral activity in their countries, and to insist on increased value-addition at home, much as the DRC, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have already done. Deals with African governments in building value-addition capacity, such as for refining and processing plants, will likely be the secondary focus of great power competition regarding metal and mineral activity. We should also expect African states to insert their interests more effectively in the resolution of the debt crisis, which is fast becoming a stage on which great power theatrics are performed. The actions of the U.S. and China here will communicate to African capitals which countries are willing to sacrifice the welfare of African economies for their own priorities and posturing. This will inform the soft power moves African governments subsequently make.

Secondly, expect heightened self-importance and hubristic aggression in the language around technology, green, and military activity. For Africa, deals regarding green and digital development with China, the U.S., and Europe will be viewed through the lens of geopolitical competition. African governments will have to pursue their own development agendas in an environment where key economies ascribe more geopolitical significance to Africa’s decisions than is healthy or warranted.

Finally, regarding Africa’s debt troubles, Beijing will continue to take steps to align with “global efforts” while pursuing its own solutions with African countries where possible. As African governments navigate the debt crisis, climate change, and great power competition, expect them to increasingly take on the strategic outlook of a multipolar world. African states will strategically leverage their position in global bodies, deepen involvement in bodies such as BRICS, and tap into the interests and capabilities of different centers of power from China, to older partners such as the EU, U.S., and new players like India, Russia, and Turkey.