September 24th, 2023

Via Middle East Eye, a look at how Saudi Arabia is redrawing the map of the future with fibre-optic cables:

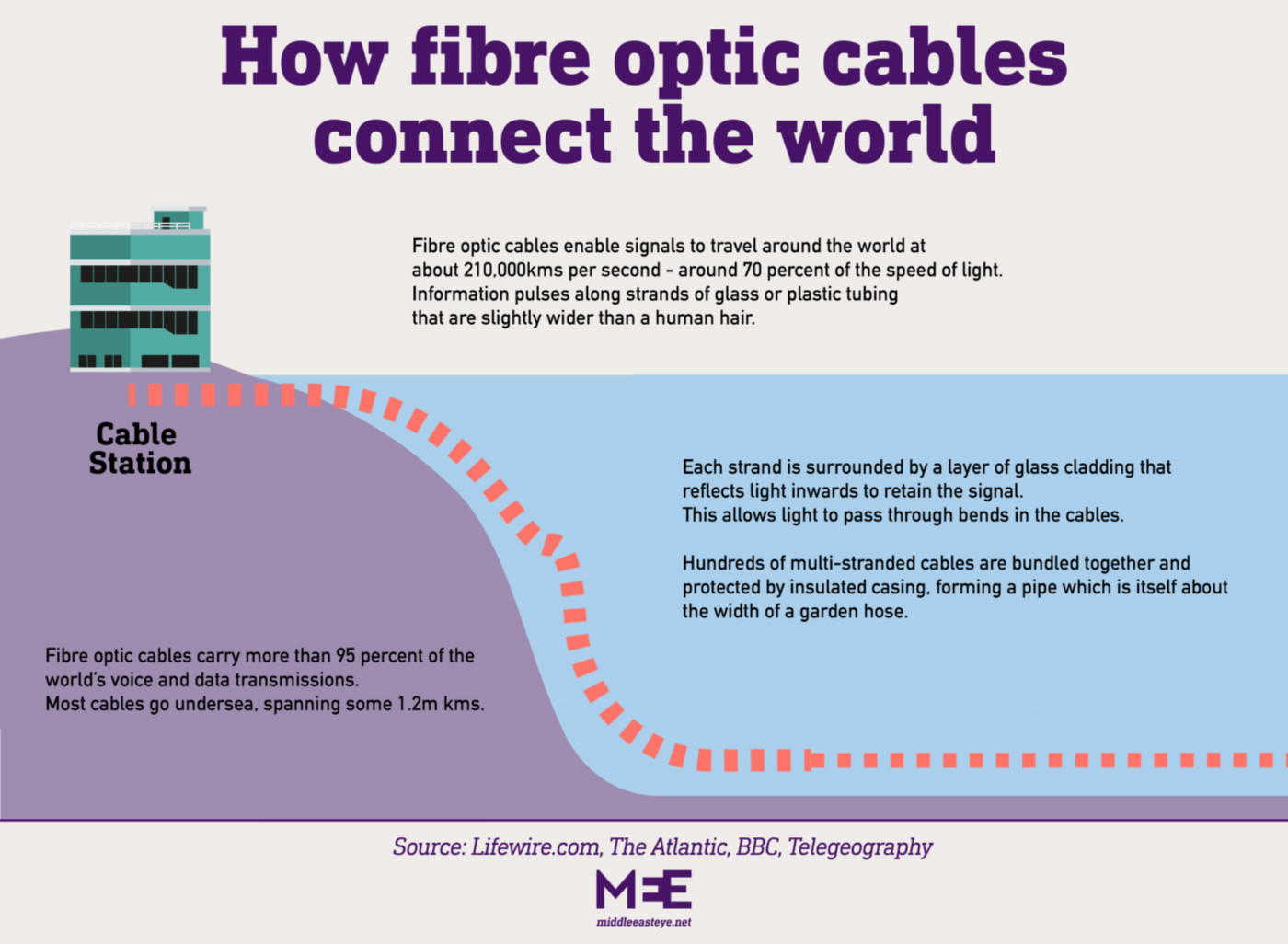

Modern life is dependent on the internet and the hundreds of underwater fibre-optic cables that criss-cross the world, carrying essential digital services from country to country in milliseconds.

Egypt has long enjoyed a dominant role as part of this network: an estimated 17 to 30 percent of all global internet connectivity runs through the Red Sea and across Egypt, linking Europe to Asia. Imagine a digital version of the more visible Suez Canal, which is owned by Egypt and is responsible for 30 percent of all global container traffic.

But, just as a grounded ship in a canal will cause delays, as happened with the Ever Given in March 2021, so Egypt is considered a choke-point by the fibre-optic cable industry due to the lack of alternative routes across a geo-strategically critical part of the world.

Egypt has been able to use this hi-tech bottleneck to its advantage for many years: a fibre-optic cable consultant told MEE, on condition of anonymity for business reasons, that state-owned Telecom Egypt (TE) charges operators the same fees to transit Egyptian territory as other companies charge their clients to go many times that distance from Singapore to the Mediterranean.

Paul Brodsky, senior analyst at telecommunications research firm TeleGeography in Washington, says: “A complaint for a long time has been that Egypt is a single point of failure for cables running between Europe and Asia, the Middle East and East Africa.

“The operator has a monopoly due to the lack of commercial diversity in cable routes. It has been the white whale of the subsea cable business. Is there a way to get away from this dependence?”

Many industry observers believe that the answer, increasingly, is yes.

In September 2020, the Abraham Accords normalised relations between Israel and the UAE and Bahrain, suggesting a potential new route for the cables from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean to bypass Egypt. But such a plan would need the cooperation and involvement of Saudi Arabia, which is not a signatory to the deal.

And so, either side of the accords, two cable projects were announced that would run through Israel to Jordan and then, separately, to Saudi Arabia.

These new projects will not unseat Cairo and its market dominance: some 16 cables run across Egypt, with five more on the drawing board. But the fibre-optic map of the Middle East is being re-drawn, with the backing of powerful regional and global actors.

Google cable to increase capacity

The first route to skip Egypt will be Google’s $400m Blue-Raman project. It will utilise two adjacent but separate cables, so it does not appear as if Israel and Saudi Arabia will be connected.

The Blue cable, which is due to open next year, runs from Europe to Tel Aviv in Israel, then crosses land to Jordan. There, it meets Google’s Raman cable, which links Jordan to Saudi Arabia.

“In many senses Raman is a conventional subsea system, from Oman around the Arabian peninsula, up through Bab al-Mandab and the Red Sea, like all cables do,” says Brodsky.

But the trick, he says, is that it will land at just a couple of places. The first is Duba, on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coastline, and just 25km from the $500bn megalopolis Neom project. From there, the cable then heads 400km further north to the Jordanian port of Aqaba, where it will meet the Blue cable on the Israeli side.

Google’s motivation for the cable is to secure its own route to its three cloud data centres in Israel, while also connecting to three data centres being developed in Saudi Arabia, and three in Qatar. “Google needs sufficient bandwidth for their cloud data centres,” says Brodsky. “Even if there’s sufficient bandwidth right now, such requirements are spurring more investments in subsea cables.”

Saudi Arabia needs more cable capacity to power high-stakes projects such as Neom (Neom.com)

Saudi Arabia needs more bandwidth for its Vision 2030 strategy of economic diversification, and is investing heavily to become the digital hub of the Middle East.

In 2022, the state-owned Saudi Telecom Company (STC) announced a $1bn investment to develop the MENA Hub to bolster its digitalisation plans and become one of the region’s leading telecoms players.

STC is also developing the kingdom’s first domestic cable, the Saudi Vision Cable (SVC), which runs along the kingdom’s western coastline from Jeddah north to Neom, and is being touted as the “first ever high-capacity submarine cable” in the Red Sea region.

“The SVC is useful to have, but in the scheme of things it is not going to make you into a hub,” says Julian Rawle, a US-based submarine fibre-optic cable consultant. “If they want to attract the hyper-scalers, such as Google, Meta and Microsoft, and set up data centres, they are going to need a lot more connectivity than they have today. The UK has over fifty cable connections.”

STC will use the MENA Hub to run the East to Med Data Corridor (EMC), which will include six new data centres and four new subsea cables. Rawle says: “EMC is kind of an umbrella name for what they’re doing in the submarine space. It is a very important part of Saudi’s Vision 2030, but they’re playing catch-up in getting that programme up-to-speed while other cables are progressing.

“But the idea of bringing in third-party cables and providing a hub for interconnection with different cable systems is new.”

Six new cables are to land in Saudi Arabia in the next three years, including Raman and SVC, adding to the 15 already in place, according to TeleGeography data. Meta’s 45,000-km 2Africa cable will also land at Jeddah, Yanbu and Duba. “This is the cable to land all cables, with its networks landing everywhere. There are a lot of cable landings on the Saudi side,” says Brodsky.

Why land cable is revolutionary

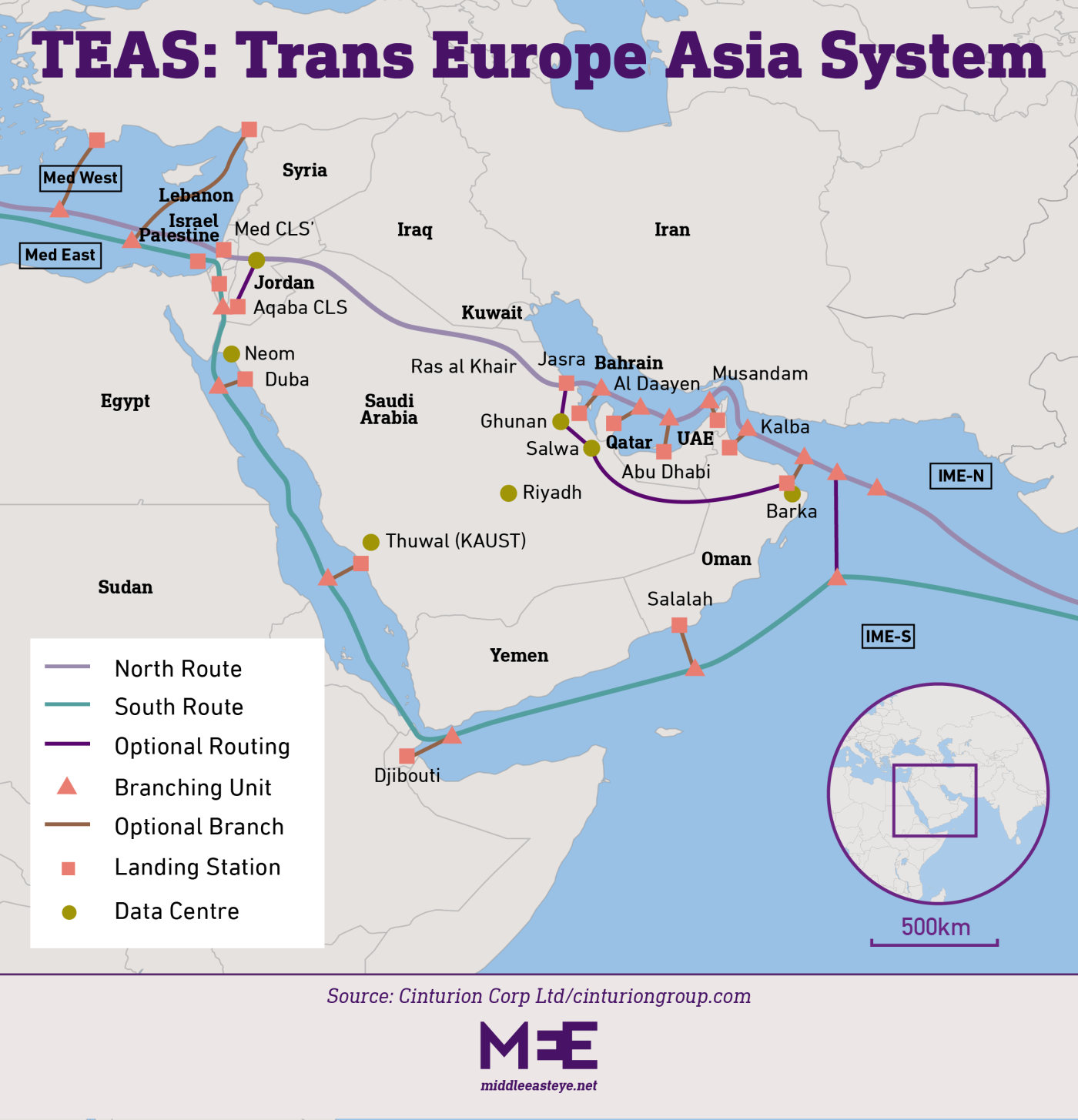

And then there is the seventh and most revolutionary cable planned for Saudi Arabia – the Trans Europe Asia System (TEAS).

Privately developed, the cable will run from Europe to India, avoiding Egypt. But unlike most other cables, part of its route will be across land.

Like Google’s Blue-Raman project, it too will be split into two: the north cable will run from Europe under the Mediterranean to Israel, then cross to Amman by land. From there it will travel east across Saudi Arabia to Ras al-Khair in the Persian Gulf.

The south route meanwhile goes through Israel, then south to Aqaba, down through the Red Sea, through the Gulf of Aden and ultimately, like the other cable, land in Mumbai, India.

“TEAS’s north cable is a revolutionary approach as it will terrestrially cross Saudi Arabia, and completely avoid the Red Sea,” says Rawle.

For a cable to go over land is unusual: operators typically use underwater routes that are regarded as safer. It is also more technically complicated to cross land, where operators have to take account of the presence of populations as well as more varied climate.

As Cinturion, the company behind TEAS, noted in an article in Submarine Telecoms Forum magazine, cables “installed in the harsh desert environments in the Middle East” require special manufacturing and installation requirements.

A terrestrial cable also requires far more splices, which link them together. For subsea cables, they are only necessary every 60 to 70km, compared to six to 10km on land. But land cables can sometimes follow a more direct route than their submarine counterparts – and for the northern half of TEAS, that involves going straight across land rather than a far more circuitous route around the Arabian Peninsula.

Rawle adds: “The route is mostly through desert, and is very sparsely populated. They are using rights of way of the GCC Interconnection Authority, the regional power transmission body, to bury the fibre-optic cables. In terms of maintenance issues, this is a less risky terrestrial route than most, and really just a question of having resources available for maintenance to do repairs when needed.”

The project is being financed by investors from Israel, the US, the UK and the Gulf, with little publicity at present.

Rachel Ziemba, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington, says the reasons for the lack of announcements is understandable.

“There is an element of behind-the-scenes here as Saudi Arabia has not signed the Abraham Accords but obviously there are security discussions and partnerships. There may be a variety of actors that don’t want the politics to trump what they see as a good economic idea.”

Yet while the TEAS project is developing at pace – an agreement was signed with Bahrain’s Alliance Networks as a cable landing partner in March – some in the cable industry doubt whether it will be completed. It has not so far been listed on TeleGeography’s submarine cable map, which is considered an industry reference source for existing and planned links.

“With Cinturion being a private start-up company, it has taken a long time to develop the TEAS project and there are still some big hurdles that need to be overcome,” says Rawle, “whereas Google can open doors a lot easier. The market views Blue-Raman as a near-certainty, but TEAS is still more uncertain.”

Avoiding Egypt’s mistakes

If Saudi Arabia is to become a major force in the cable operations market then it needs to avoid some of the mistakes made by Egypt, including not aggravating the market by over-charging, nor squandering the opportunity to become a data hub.

“A gentle reminder to the Saudis that if they want to be a regional hub they have to make it sufficiently attractive,” says Rawle. “Egypt chose to use their position to the maximum extent possible to generate revenue without investing in becoming a hub.”

Egypt, he says, has ended up a conduit between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean rather than take a longer-term view, as Saudi Arabia seems to be doing.

“They offer an alternative to Egypt, and can become a hub for the region where all hyper-scalers bring content and manage it out of the country.”

The ongoing jostling between the UAE and Saudi Arabia to become the Gulf’s economic and digital hub is also expected to force Riyadh’s hand.

James Shires, a senior research fellow at Chatham House and author of The Politics of Cybersecurity in the Middle East, says that unless the UAE’s economic position comes under threat, there will always be more free market competition between the UAE and Saudi Arabia that will be favourable to business.

“That level of competition will prevent the Saudis putting undue economic pressure on this kind of cable traffic.”

Cairo, meanwhile, has recognised the growing diversity in the MENA cable sector and reportedly moderated the transit fees it charges operators.

“If all these new cables play out, there will be a new balance in the regional cable market,” says Rawle. “There will not be winners or losers, but better resilience in the overall network that connects East to West.”

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.