Turkey is on a diplomatic offensive to justify a foreign policy that some believe is too friendly to too many. On Aug. 11, Turkish Defense Minister Yasar Guler said in an interview that Turkey’s NATO membership does not preclude it from developing relations with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. This comes roughly a month after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said point blank that Turkey wants to be a part of the SCO and after Turkey’s ambassador to Beijing explained that joining the SCO and the BRICS would complement rather than conflict with its membership in Western organizations.

This is puzzling for many. The SCO is a political, economic and security alliance founded in 2001 by China and Russia that has since expanded to include Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, India, Pakistan, Iran and Belarus. It means to enhance cooperation and trust among member states, maintain regional security and stability, combat terrorism and extremism, and promote economic development. It’s not a military organization, so it’s not a direct competitor to NATO, but many believe it is an organization that legitimizes illiberal norms and opens exceptions to otherwise applicable international norms, providing a sort of haven for nations that want to avoid the scrutiny of Western-dominated organizations. (Turkey’s interest in joining isn’t exactly new, but it has shown a much greater sense of urgency lately.) The BRICS, meanwhile, comprises countries that seek to challenge the political and economic power of the wealthier nations of North America and Western Europe. To many in the West, it is considered nothing less than a challenge to its own model for the world.

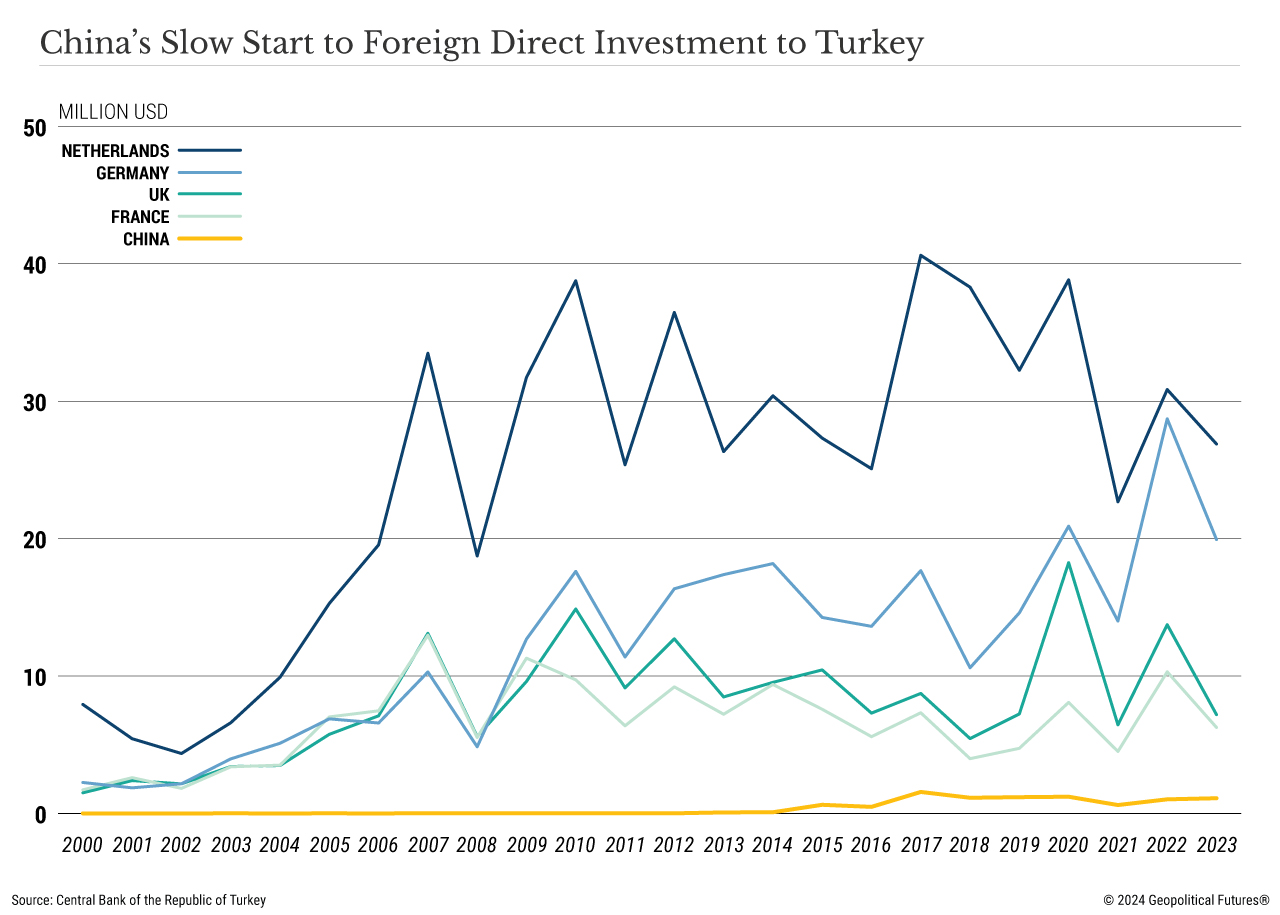

In seeking to work with both groups, Turkey has shown a willingness to maintain good working relations with the two biggest challengers to Western power: Russia and China. Turkey has cultivated a cautious but neighborly relationship with Russia, but its ties to China have recently begun to grow. Bilateral trade has increased over the past five years, and official visits have intensified. (Turkey’s ministers of foreign affairs, energy and natural resources, and industry and technology have all traveled to Beijing this year.) Though recent statements suggest increased security ties between the two countries, Sino-Turkish relations are in fact based on shared economic interests.

Given the current international business environment, the challenge of global economic restructuring, the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fallout of the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, how Turkey and China shape their relationship is critical to understanding the future of global trade and investment corridors. While the West is considering de-risking or decoupling for economic and security reasons, Turkey seems to be moving in the opposite direction. Its strategic location, its membership in Western organizations, and its economic ties to the European Union will necessarily shape current and future security arrangements.

Turkey’s interest in China is straightforward: It needs investment in key sectors to enhance its energy security and sustain its technological development. It also needs foreign capital to tame inflation (which stands above 60 percent), reinforce its currency and pay for ongoing reconstruction following last year’s devastating earthquake. Crucially, Ankara knows that China needs to address some of its own economic problems, which can be at least tempered with new trade routes and markets. It clearly believes they are ideally suited to help each other out.

The Turkish government has urged China to increase investment in a variety of sectors – solar and nuclear energy, high-tech infrastructure and AI. And the newly constructed Sinovac vaccine center is a good example of how the two countries can improve ties in specific areas. But a much more important example – the agreement between Chinese carmaker BYD and Turkey to build a production plant in Manisa province – shows how the two can parlay their ties into something more. The agreement came after a slew of EU measures to lower imports of Chinese electronic vehicles into the bloc. Among them was an increase in customs tariffs from 10 percent to 17.4 percent specifically levied against BYD. Though the tariffs are temporary, the EU will likely meet in October to decide whether they become permanent. If they do, they will almost certainly further decrease BYD’s market share in Europe.

China’s loss was Turkey’s gain. After the EU enacted its protectionist measures, Ankara imposed an additional 40 percent tariff on imports of vehicles from China – only to later exempt Chinese companies that invest in Turkey. The exemption was tailored to suit BYD’s needs but may well attract other manufacturers. For China, there is an even greater benefit. Turkey and the EU share a customs union that states that anything made in Turkey is exempt from customs duties when sold to the EU. Moreover, factories set up in Turkey do not have to apply EU regulations to labor or production standards. So long as the final products meet the European consumers’ standards, they can be sold in the EU market. This translates into lower production costs.

This explains why Erdogan, Industry Minister Mehmet Fatih Kacir and BYD Chairman Wang Chuanfu attended the agreement’s signing ceremony in Istanbul on July 8 – just four days after Erdogan attended an SCO summit in Kazakhstan to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping.Besides the immediate business benefits Turkey’s proximity to Europe offers Chinese investors, there is also the matter of long-term strategy. From China’s point of view, its growing economic presence in Turkey is part and parcel of its growing use of the Middle Corridor – itself a part of the Belt and Road Initiative – as the war in Ukraine restricts use of the Northern Corridor, and as the Gaza war threatens transit through the Red Sea. Given China’s near-existential need to sell its goods, new trade routes and new markets mean more than just dollars and cents.

The same could be said of Turkey. For Ankara, the money is nice, but the improvement in its strategic posture is nicer. With Russia weakening as a result of the Ukraine war, Turkey sees China as the only viable challenger to Western (read: American) global dominance. It may maintain a close alliance with Washington, but it wants to develop its approach to regional security. This led Turkey to purchase Russian-made S-400 air defense systems, which ultimately caused its expulsion from the U.S.’ F-35 program. It was only Turkey’s agreement to ratify Swedish NATO membership that rekindled its relations with the U.S. Ankara has now agreed to pay $23 billion for the most sophisticated variant of the F-16 aircraft. This is just one example of how Turkey uses diplomacy to gain leverage in negotiations with the West. Its budding relationship with China is absolutely part of that strategy.

Overall, what seems to be a new foreign policy oriented toward China is a planned, pragmatic move by Turkey to increase its strategic options and autonomy, which eventually will be turned into bargaining chips in discussions with NATO and the U.S. The profits are icing on the cake. That China’s leadership will avoid confronting the West over the matter will only benefit Turkey, which wants not so much to destroy trans-Atlantic security arrangements but to gain marginal advantages from exploiting them.

The Truth About Turkey’s ‘Pivot’ to China

August 16th, 2024

August 16th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, an article on Turkey’s pivot to China:

This entry was posted on Friday, August 16th, 2024 at 4:47 am and is filed under China, Turkey. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.