Cuba has had a bad week, even by Cuba’s standards. It suffered four nationwide power outages in a 48-hour period, only to be struck full force by Hurricane Oscar. The two events brought the precarity of Cuban infrastructure – particularly its power grid – to the fore. Much of the subsequent conversation has focused on the causes of the blackouts and the degree to which they can be chalked up to government neglect. Largely absent from the discourse is that many of Cuba’s problems are structural – and that many of their solutions may bring unwanted changes for Havana.

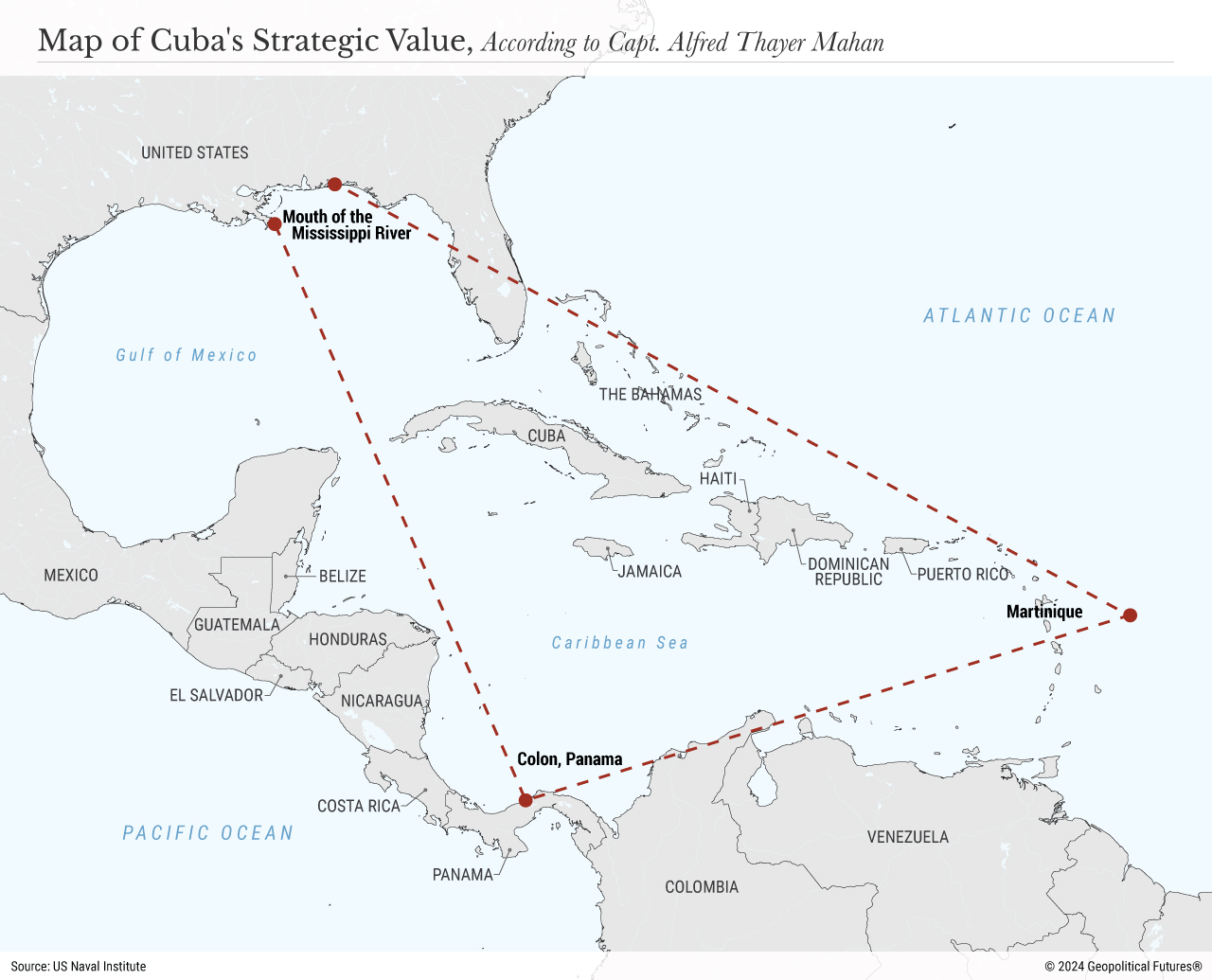

Alfred Thayer Mahan, the esteemed naval strategist and geopolitical theoretician, provided the framework for why a country as small as Cuba can be so important. He argued that the strategic value of a place is based on its proximity to operations (position), the defensibility of harbors and ports (military strength), and its ability to quickly secure supplies (resources). Cuba checks all three boxes. It sits along multiple sea lanes on which U.S., Mexican and international commerce relies. It is located near the mouth of the Mississippi River, the launchpad of so many U.S. agricultural exports; near the city of Colon, where the Panama Canal terminates in the Caribbean Sea; and near the Lesser Antilles, which gives way to the Atlantic Ocean. Cuba is thus a critical component to maritime trade, Caribbean stability and American prosperity. This is why Cuban stability plays such an outsized role in U.S. foreign policy.

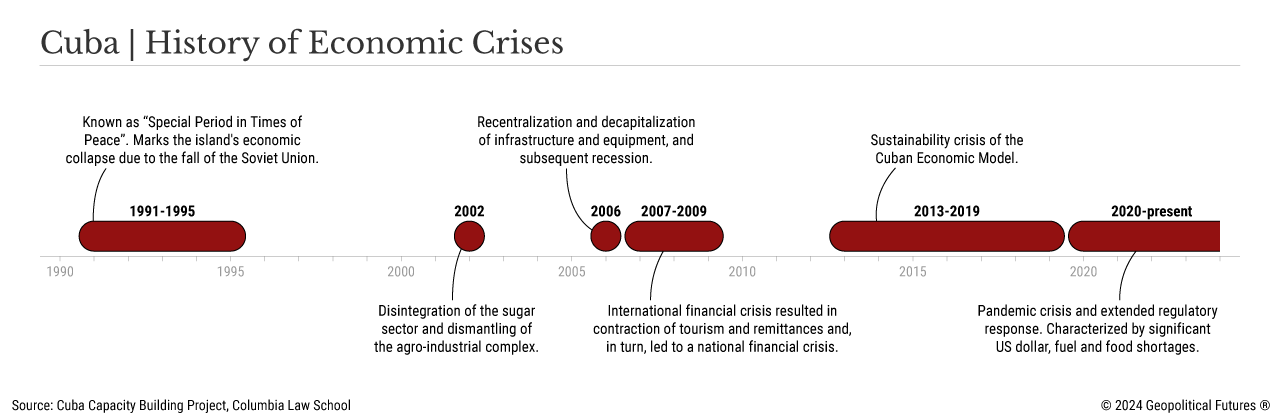

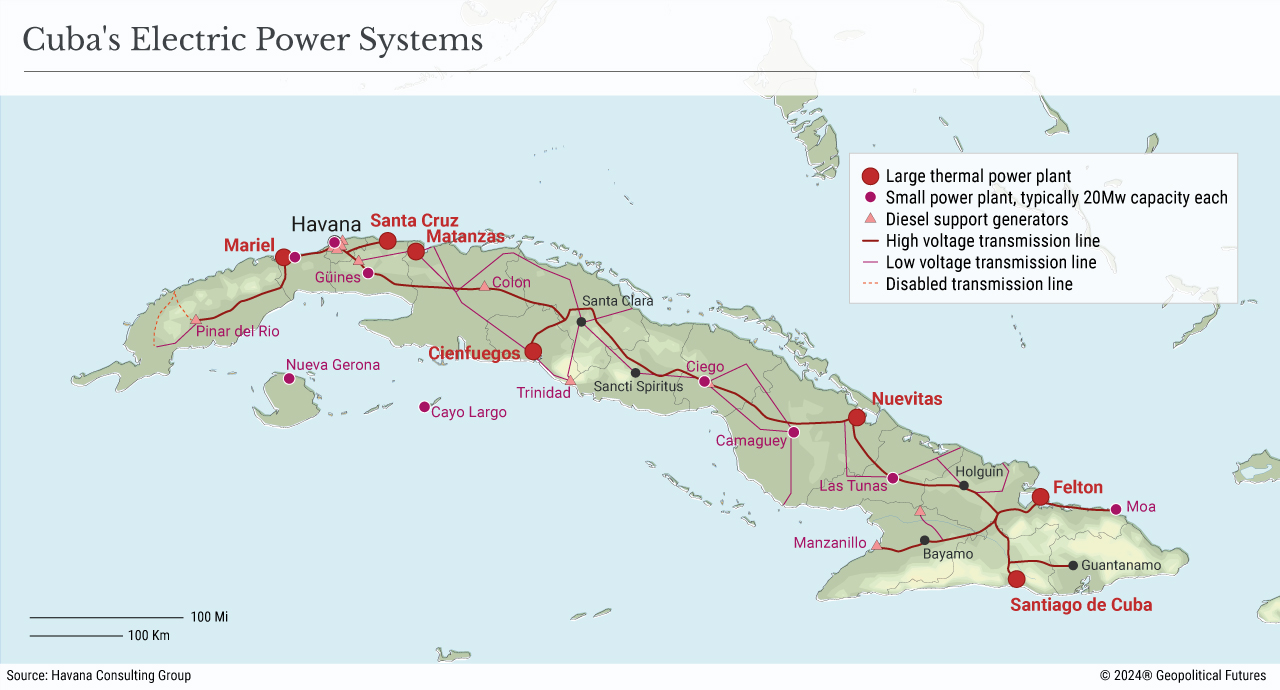

Problems with Cuba’s electrical grid undermine the Cuban economy and, in doing so, potentially destabilize the island. Cuba’s economic conditions today are as bad as or worse than they were in 1993, its worst economic year on record. Though its economy has modestly rebounded since then, the past 30 years have been marked by one crisis after another – some indigenous, some exogenous. Its current economic crisis is a hangover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel restrictions decimated Cuba’s tourist industry, which caused U.S. dollars, necessary for importing vital goods, to dry up. Fuel shortages caused agriculture producers, electricity plants, industries and households all to compete for slices of an increasingly smaller pie. Food shortages ensued as the government prioritized the recovery of tourism. Government investment in non-tourism sectors declined, with utilities receiving a paltry 6.6 percent of investment in 2022. Add to this the fact that since 1990 demand for electricity has outpaced supply, and you can see why the grid is in such disrepair.

For Havana, repairing and modernizing the grid has been and will continue to be difficult. Much of its existing infrastructure, including its thermal plants, was built directly or indirectly by the Soviet Union, which helped triple the country’s generation capacity after 1975. But major Soviet assistance ended in the 1980s, so even the youngest of Cuba’s generation centers are some 40 years old. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the U.S. embargo complicated any government efforts to import the materials needed to maintain and modernize its electricity infrastructure. They also made it harder to import fuel needed to power the generation plants. As a result, Cuba resorted to using domestic crude, which had higher concentrations of sulfur and water than imported oil and damaged thermoelectric boilers and other equipment.

In other words, the scarcity of fuel and the dilapidation of infrastructure are the main culprits behind this week’s recent outages. Local analysts conservatively estimate that fixing Cuba’s electricity grid will cost approximately $10 billion, equal to roughly 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

Immediate aid may help Cuba in the short term, but it will not fix its fundamental challenges. Even so, the aid that has been offered could shed light on which countries want to enhance their influence in the country. At the time of writing, the Cuban government is in talks with at least five foreign governments: Barbados, Colombia, Mexico, Russia and Venezuela. Barbados’ offer should be seen as an act of solidarity; the country is too small to offer enough to move the needle. Venezuela and Colombia fall into a similar category in that they are limited in what they can offer; Colombia’s government is busy dealing with an economic slowdown, declining government funds and controversial reforms, and Venezuela, once a major oil supplier to Cuba, has been forced to drastically reduce its shipments by domestic political and economic issues. (In the first half of 2024, Venezuela provided Cuba with 27,000 barrels of oil per day, a nearly 50 percent drop from last year.)

Given their strategic interests, Mexico and Russia are the names that stick out the most. Mexico borders the Caribbean and thus sees Cuban stability as a security issue. It has already used “humanitarian aid” as pretext for providing oil and other goods to Cuba. In 2022, for example, it gave $700,000 worth of parts and equipment to Cuba’s thermoelectric plants. (It is unclear whether the newly inaugurated Mexican president, Claudia Sheinbaum, will follow in her predecessor’s footsteps.) Russia values Cuba as a source of pressure and pain for the U.S. Moscow has issued more than $1 billion worth of credit to Cuba over the past decade, some of which was earmarked for improving the electrical grid and some of which has since been canceled. It has become Cuba’s biggest supplier of oil. The problem for Russia is that it is fighting a war in Ukraine and is hamstrung by international sanctions.

Noticeably absent from the list is China. At a strategic level, it makes sense for China to seek influence in Cuba as part of its strategy to gain leverage over the U.S. in the Western Hemisphere. Hence China’s large lines of credit and investment projects on the island in the 2000s and 2010s. However, it is preoccupied with its own economic concerns – which make Cuba an unattractive partner for the time being. The Cuban government owes hundreds of millions of dollars to major Chinese companies, and Beijing is tired of waiting to collect.

The U.S., meanwhile, is watching from the not-so-distant sidelines. Washington’s ultimate goal is to have the Castro regime replaced with a more U.S.-friendly government that would enable it to reclaim the influence it has lost there. Over the past few years, low-level talks with Havana have advanced, but fundamental differences have prevented any substantial changes. The one thing that could spur a change in the status quo is public unrest, which Washington would likely support. Protests in response to the blackouts have been reported, and broader social discontent is palpable. But all available reports suggest Cuban security forces have managed to keep it all in check. Moreover, Cuban citizens, now as always, tend to prefer to leave the country rather than to mobilize en masse. An estimated 850,000 Cubans entered the U.S. from 2022 to 2024 alone. A leading Cuban economist and demographer estimates that Cuba’s population has fallen by 18 percent since 2022, putting the current population on the island at about 8.62 million people, not the 11 million reported by the government. Under these circumstances, the U.S. is unlikely to help Cuba with its grid problems, though it may be tacitly supporting Mexico’s efforts since their interests align.

The bottom line is that Cuba’s need to overhaul its electrical grid opens the door for outside patrons. Revamping the island’s energy matrix will require a shift to renewable energy sources, particularly solar. On this front, China, the U.S., Brazil and certain European countries could become valuable partners because they have deeper pockets and eager companies to foot the bill. Improved governance, resource management and macroeconomic stabilization will have to come from within, not without. Even so, whoever ends up helping Cuba rebuild its power grid will hold one of the keys to unlocking economic recovery on the island and influence in the Caribbean.

Cuba’s Long-Standing Power Problems

October 23rd, 2024

October 23rd, 2024

Courtesy of Geopolitical Futures, analysis of Cuba’s recent power blackout crises:

This entry was posted on Wednesday, October 23rd, 2024 at 9:36 am and is filed under Cuba. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.