Nearly a decade on, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has come to define China’s global development engagement. But as US and European relations with China deteriorate, the BRI – and infrastructure finance – have become focal points for geopolitical competition, spurring in recent years a spate of counter-offers, often with the explicit goal of countering China. These include the UK’s homegrown Clean Green Initiative (CGI), the EU’s Global Gateway and the US-led Build Back Better World (B3W) – all of which have eventually coalesced under the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

This marks a welcome move from G7 countries into the infrastructure space and a convergence of narratives around development. Meanwhile, China appears to shift increasingly towards a ‘traditional’, poverty-oriented focus under the Global Development Initiative (GDI).

The plethora of development and infrastructure initiatives should be a boon for the global south countries that face a continued infrastructure gap, particularly in climate adaptation and resilience.

However, while China’s pivot is likely to give it more freedom for manoeuvre, the question of whether G7 initiatives can deliver is less certain. Rhetoric is not enough: competing infrastructure initiatives need to deliver in terms of finance and action.

The BRI takes a sabbatical

While US and EU policymakers have centred on the BRI as a competitor, the initiative has ironically been more or less shelved in China over the last five years. This has been dramatically visible not only in the decline in China’s policy bank lending after 2016, preceding the Covid-19 pandemic, but also at the political level. Mentions of the BRI have all but disappeared from President Xi Jinping’s official speeches, and the BRI forums – which were prominent platforms for handshaking between Xi and other political leaders in 2017 and 2019 – were downgraded to an ‘advisory council’ meeting in 2021, led instead by Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

International criticism of the BRI’s environmental impact has played a part in this decision, as have accusations of it being a ‘debt-trap’. However, the fall in overseas lending from policy banks has been a long-term trend that has followed China’s domestic economic cycles: the economic slowdown after 2013, the 2015 financial crisis and internal regulatory tightening in 2017.

As a narrative, the BRI will not retire completely, and a third forum in 2023 has been floated by Xi. But the emphasis will shift, focusing instead on ‘small and beautiful’ projects.

As Xi cements his third term in power, stability is the top priority. With the tightening on overseas lending, growing domestic economic pressures from Covid-19 and stirring civil unrest, the heyday of China’s overseas infrastructure finance is likely – for the time being – to be over.

Global Development Initiative: China returns to poverty reduction

As the BRI takes a back seat in China’s public diplomacy, over the last year new initiatives have taken root. The Global Development Initiative (GDI), first announced at the UN in November 2021, has become the new leitmotif in Xi’s outward diplomacy, including at the recent G20 summit. Alongside it, the less prominent Global Security Initiative (GSI) was announced in April this year. Just as nebulous in substance as the BRI when it first launched, these initiatives serve as a blank slate for engagement with global south partners, free of the negative attention that has bogged down the BRI in the last five years. Interestingly, the GDI is thematically closer to the ‘traditional’ OECD-DAC narratives of development as a tool for poverty reduction than the connectivity-focused BRI.

Currently, the GDI is oriented around eight pillars: poverty reduction, food security, pandemic response and vaccines, financing for development, climate change and green development, industrialisation, digital economy, and ‘digital-era’ connectivity. The focus on industrialisation, digitalisation and connectivity overlaps substantially with the existing BRI (though infrastructure as a theme is notably understated). This offers a diversity of platforms, as well as flexibility in how China can strategically label its development cooperation.

Like the BRI, the GDI (and GSI) follow a similar pattern whereby the platform is announced first with the content and substance coming later. While it has not yet attained the same breadth of membership as the BRI, the GDI’s ‘Group of Friends’ counts more than 60 members – a sign that some global south countries still view China as an attractive partner. At a time when Western donors are increasingly withdrawing from their multilateral commitments, the GDI is consciously framed as multilateral. It is also explicitly aligned with both the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the revived UN Fund for South-South Cooperation, mirroring the Silk Road Fund created for the BRI a decade ago. This demonstrates continued Chinese support, normatively and financially, of the multilateral system.

New belts, new roads – new finance?

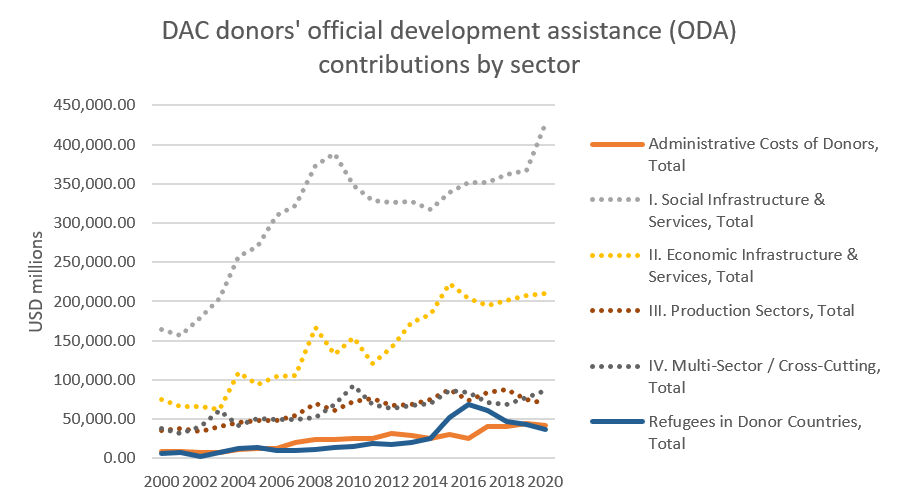

The decline in BRI lending puts even more pressure on other financiers to meet investment needs in the global south. However, in recent years infrastructure financing flows from DAC donors to economic and productive sectors have plateaued or even fallen, while domestic ODA spending (e.g. administrative costs and refugee spending) has grown (see Figure 1). BRI alternatives in the G7 PGII pledged a total of $600 billion, including $200 billion from the US, $300 billion by 2027 under the EU Global Gateway and $65 billion from Japan under its Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI). Spread over five years, however, these are unlikely to mark a huge shift from existing trends.

Figure 1

Much of the EU Global Gateway finance is merely a ‘repackaging’ of existing facilities and development commitments from member states and development financial institutions (DFIs), and captures a potential ‘mobilisation’ without actual investment, being dependent on private sector participation (and their incentives to do so). The track record of G7 countries and their DFIs in mobilising this private sector finance for low-income countries does not inspire confidence. Unlike Chinese state-owned enterprises, G7 countries have a much weaker institutional setup to credibly incentivise private sector actors to invest overseas.

The geopolitical rationale behind these initiatives also risks becoming a weakness. Turning development and infrastructure finance into an exclusionary initiative misses the potential gains or complementarities that could come from cooperation, and risks inefficient competition over the same project pipelines. Moreover, if competition with the BRI and China is the primary objective, what incentive is there to commit such finance if the competition disappears (which may well be the case as China’s leaders remain occupied with more pressing domestic concerns)?

Competing with the BRI may also prove to be impossible. Chinese banks offered finance at an unthinkable scale, at low cost and at a speed that was highly attractive both to leaders campaigning for elections and the domestic growth needs of borrowing countries. At a time of high commodity prices, governments had the space and capability to borrow. However, with debt distress intensifying across the world, this model of debt-financed infrastructure may no longer be scalable or politically feasible for many countries.

If European and American development partners are serious on infrastructure finance, there are other ways they can support investment and reduce borrower country dependence on Chinese finance:

- Support reform of multilateral development banks (MDBs). MDBs hold huge financial and technical firepower in the area of infrastructure, and will be crucial players in climate finance in low-income countries. But they need capital and key governance reforms in order to streamline bureaucratic approval processes and take greater risks. This will make them more agile, innovative and attractive as partners in addressing the climate crisis and other global challenges.

- Strengthen collaboration between public development banks to increase access to finance. Collaboration between public development banks – embodied in the Finance in Common movement – can be a way to increase access to affordable finance and develop financial markets in low-income countries. With additional technical and financial capacity, the national development banks of borrower countries can be key partners for MDBs and international partners in project preparation, building a pipeline of bankable projects for investment.

- Take the lead in coordinating a predictable post-Covid debt workout structure. Countries facing debt distress have uncertain access to international capital, hindering their ability to borrow and invest. G7 countries should work with the G20 to standardise the implementation and procedural transparency of the Common Framework, which has been painfully slow to date, and push for coordinated debt write-offs from the public and private sectors, providing governments with the fiscal space for critical infrastructure investment.

- Stop making development finance a zero-sum game. Taking lessons from the BRI, G7 initiatives could reframe motivations on the positive economic potential of emerging economies. There is huge potential in aligning and embedding infrastructure programmes in regional agendas (through coordinating with the emerging African Continental Free Trade Area, for instance). These programmes can be shaped by regional priorities, while there may also be positive-sum synergies in coordinating with China, its emerging GDI and with other actors.

Amid the intensifying geopolitical competition, there is a convergence in narrative between the G7 and China on infrastructure investment that could be of huge benefit to global south economies. However, G7 partners need to go beyond the rhetoric of rivalry to deliver credible results.