SEOUL – In October, the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China endorsed another five-year term for President Xi Jinping, effectively ending the practice of limiting the presidency to two terms. It was thus also an unmistakable break with the tradition of collective leadership established in the late 1970s, after the end of Mao Zedong’s one-man rule.

China is the most notable recent case of simultaneous economic growth and increasing authoritarianism. But it is not the first. Not long ago, South Korea had its own version of “developmental dictatorship.” For much of the twentieth century, Korean leaders, like China’s today, prioritized economic catch-up through mercantilist growth over a democratic transition – until democrats refused to wait any longer.

Simply put, the Korean story is one in which political authoritarianism was accompanied by miraculously fast economic growth, which in turn became the material basis for a democratic push led by the middle class. Could China take a similar path?

When Park Chung-hee came to power in South Korea by military coup in 1961, the country was one of the world’s poorest. Then, in 1972, after several close elections, he changed the constitution so that he could be elected indirectly by a special body comprising pro-government representatives, enabling him to serve as president for many consecutive terms. Civil liberties were the next target. In 1974, the National Emergency Decree forbade all manner of gatherings and meetings, suppressed press freedom, and banned labor strikes.

Park’s strategy produced mixed results. The economy continued to grow, but political repression failed to stifle the pro-democracy movement. Korea suffered from political crisis and turmoil, which culminated in the sudden death of Park in 1979. But Park’s death did not trigger a political transition. On the contrary, a former military general, Chun Doo-hwan, became president and declared martial law.

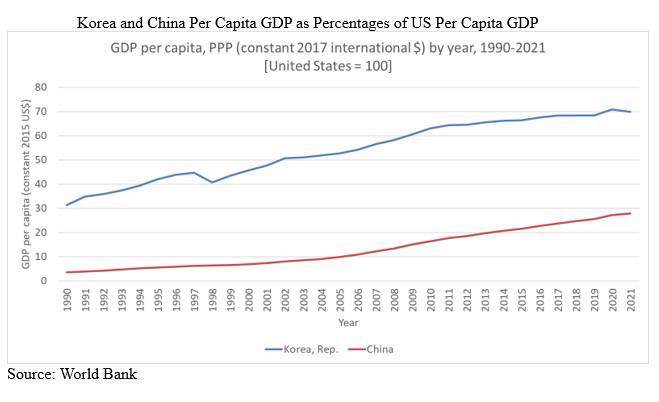

By the mid-1980s, under Chun’s leadership, South Korea’s per capita GDP reached roughly 30% of the level in the United States. By then, thanks to continued economic growth, Korea had a strong middle class, whose members were once again mobilizing street protests to demand a return to full democracy. In 1987, mass demonstrations by white-collar and industrial workers, students, and activists spurred the demise of Park’s 1972 constitution. The people would once again elect their leaders.

But the story did not immediately have a happy ending. Progress toward full democracy was very gradual. It took several years for a civilian, pro-democracy fighter, Kim Young-sam, to be elected president. But he was indeed elected. And during Kim’s term, South Korea’s per capita GDP reached 40% of US GDP, enabling the country to join the OECD in 1996.

This brings us back to China, which has now reached nearly 30% of US GDP per capita and has been closing the gap by one percentage point per year, on average, for the last seven years. If this trend continues, China could reach 40% of US GDP in ten years, or at least by the mid-2030s.

But while China’s economic trajectory resembles South Korea’s in the late twentieth century, there has not been a similar process of democratization. Will there be? Like Korea around the mid-1980s, China has already generated a large middle class. And the fact that China’s government responded to recent anti-lockdown demonstrations by abandoning key elements of its zero-COVID policy is evidence not only of the potential power of middle-class Chinese, but also of the limitations of top-down policies

Cynical observers might shrug, dismissing the possibility that China would ever grant its citizens democratic rights. But if it does happen, Chinese leaders can learn from Korea’s ex.

A less-noticed aspect of the Korean miracle is that, despite years of chronic political turmoil and crisis, the economy continued to grow, and household income increased steadily. The reason was that most pro-democracy demonstrations were relatively peaceful and did not threaten property rights, owing to middle-class protesters’ stake in the economy. And because both sides ultimately agreed to respect the constitution and try to win elections, the result was a return to democratic order, not a revolution.

Nonviolence during the democratization process is important for its own sake and to avoid jeopardizing the economy and risking further chaos. China has yet to accept that it needs to have a clear and transparent process of electing its top leaders, or that stable democracy requires genuine political competition. For the sake of all it has already achieved, it should change that.

South Korea is often cited as evidence that democratization is indispensable to achieving high-income status. It is true that China may reach that level by the mid-2030s without competitive elections or even significant liberalization. Still, the next 10-15 years may open a window for democratization of the kind that Koreans scrambled through from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. If so, it will be up to China’s leaders and people – especially middle-class Chinese – to take advantage.

A Korean Trajectory for China?

December 15th, 2022

December 15th, 2022

Via Project Syndicate, interesting commentary on potential economic similarities between Korea and China:

China is perhaps the most notable recent case of simultaneous economic growth and increasing authoritarianism. But South Korea’s recent history shows how a vibrant economy can lead to the emergence of a large middle class – and, with it, demands for democratization.

This entry was posted on Thursday, December 15th, 2022 at 1:33 pm and is filed under China. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.