April 11th, 2023

Courtesy of STRATFOR Worldview, first part of an ongoing series that explores the opportunities and risks provided by Africa’s expected population boom in the coming decades:

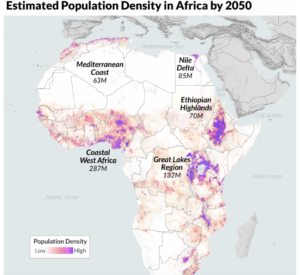

At a time when many countries around the world are grappling with demographic declines, Africa remains poised for rapid population growth. According to the United Nations’ 2022 World Population Prospect report, countries in sub-Saharan Africa are expected to ”contribute more than half of the global population increase anticipated through 2050.” Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is currently growing at 2.7% per year, more than twice as fast as South Asia (1.2%) and Latin America (0.9%). The number of people living below the Sahara desert is expected to double in the next 50 years to more than 3 billion, with coastal West Africa, the Great Lakes region and the Ethiopian highlands seeing the sharpest population spikes.

These estimates, of course, are only projections based on current fertility, mortality and migration trends — all of which could change in the coming decades due to various factors, such as increased access to education and service sector jobs. But sub-Saharan Africa has so many women of childbearing age that even if most decided to have fewer children today, the region’s population would keep growing — a phenomenon demographers call ”population momentum.”

What’s at Stake

Sub-Saharan Africa’s demographic change has the potential to create political, economic and humanitarian problems of massive proportions. But it also offers major new possibilities for growth and prosperity. The increase in population will be accompanied by changes in the age structure of the region’s population (or ”population pyramid”). As the youth population and the number of Africans over 65 years old shrink, the working-age population will grow for decades to come.

Sociologists refer to this high ratio of working-aged people to dependents as the ”demographic dividend,” or the potential to unlock economic growth through an expanding labor market and dwindling populations of children and elderly. The extent to which African states will capitalize on this opportunity will vary greatly. Some countries will innovate to improve agricultural production, job growth and service delivery. Others, however, will struggle to reach ”demographic fatigue,” wherein a lack of financial resources leaves them unable to stabilize population growth and effectively mitigate risks like land degradation, irregular migration, insecurity and poverty.

African countries’ responses to their exploding populations will have far-reaching implications, ranging from migration to the global balance of power. Hunger is already a problem across the Continent. But with a projected 3 billion mouths to feed by 2070, agricultural land will become increasingly scarce as agricultural production struggles to keep pace with booming demand, while urbanization leads to declines in agricultural labor — posing new challenges to food security that could drive migratory flows to more developed parts of the world at ever-increasing rates.

Technological advances will also make Africa’s youth populations more connected than ever. And these younger Africans will increasingly demand greater economic stability and social protections from their respective governments, in some cases precipitating political liberalization and in others surges in authoritarianism. The coming surge of young adults will also pose new risks to social instability on a continent with relatively young governing institutions, potentially sparking global social, environmental and/or political movements that challenge the ruling order. Furthermore, African states’ political ideologies and geopolitical orientations will likely become all the more important amid the accelerating transition to a multipolar world order, as is already evident in Russian, Chinese and Western competition for influence in Africa.

Indicators for Positive Adaptation

While sub-Saharan Africa’s population boom by 2050 is largely a foregone conclusion, the pace of population growth beyond 2050 is not. With effective policymaking, governments can still encourage lower fertility rates so that the supply of resources and services may eventually catch up with demand. The United Nations estimates that current efforts to curb population growth will only be felt after 2050, which means that the demographic interventions African governments undertake over the next few years will be critical in determining whether they catalyze population growth into ”demographic dividends” or reach states of ”demographic fatigue.”

To better understand the associated risks and opportunities ahead, there are several key factors that will help indicate African countries’ capacity to harness their population growth as an engine for political, economic and social progress:

Girls’ education. Few inputs have a stronger influence on fertility rates than girls’ education. African women with no formal education tend to have six or more children, whereas women who have completed primary school tend to have about four kids and those who have finished secondary school have an average of two. Beyond reducing the number of children per family, quality girls’ education is also correlated with improvements in quality of life. With fewer children, families can invest more in healthcare, education and savings, leading to improvements in the skilled labor market. Furthermore, smaller families can increase the availability of educational funding per child, leading to compounding improvements in school enrollment and quality of education. The United Nations estimates that there is a 20-year lag between changes in education and changes in fertility, meaning policy changes that impact girls’ education over the next five years will have a direct impact on African countries’ fertility rates in the 2040s and 50s.

Agricultural innovation and production. Food security will be central to African governments’ capacity to catalyze population expansion into growth opportunities. In West Africa and the Great Lakes region, food insecurity already drives destabilizing migration outflows and makes communities more vulnerable to insurgencies and extremism. In West Africa alone, over 24 million people are estimated to already be in need of food assistance. Huge population increases will very likely exacerbate these challenges unless African governments can boost agricultural productivity and trade to feed their respective citizens. While this can take myriad forms, countries’ capacity to avoid a larger food crisis will largely hinge on their government’s efforts to attract investments into their agricultural sectors, which could put downward pressure on food prices, boost innovation and agro-processing, and enable higher returns to public sector investment in agriculture.

Urban infrastructure and services. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population boom is expected to spur accelerated urbanization as more Africans migrate from rural areas to city centers in search of work. In 2015, 50% of Africans lived in urban areas, up from 31% in 1990, according to The Economist. By 2050, the share will rise to more than 70%. Urbanization has generally benefited national development and the incomes of individual workers, given that wages in African cities are about twice as high as in the countryside. But the infrastructure and services of those cities have struggled to keep pace with their growing populations, leaving more than half of urban residents in sub-Saharan Africa living in slums. Ken Opalo, a researcher at Georgetown University, calls this phenomenon the ”ruralization of urban areas,” or subsistence living in cities. As African cities continue to expand over the next decade, a combination of accelerating urbanization and ”ruralization” of metropolitan areas will present challenges ranging from lack of access to water, power and transportation services to insufficient natural disaster response. Development of urban infrastructure, including public utilities like waste disposal, water and electricity, will be crucial to governments’ ability to create jobs, attract investment and ensure political stability.

Job creation. Mass job creation is a necessity for African countries to reap the economic benefits of their growing working-age population. Without more jobs, an influx in labor supply will result in unemployment and underemployment, likely triggering political instability and crime — especially among Africa’s budding cohort of young adults. Some academics have suggested that the solution to unemployment and underdevelopment lies in expanding Africa’s manufacturing sectors, often pointing to Asia’s rapid, manufacturing-fueled economic development. But Africa is unlikely to replace Asia as the world’s manufacturing hub given Africa’s lack of established infrastructure and the fact that Asia maintains its own labor reserves that will compete with African labor growth. As such, African governments will be forced to seek alternatives that are attractive to an increasingly politically active population, likely in the form of high-productivity formal sector jobs, as opposed to the low-wage informal jobs that proliferate in high-population centers like Nigeria. For job creation to be an effective catalyst for growth, it must be sustainable. This means that current attempts to employ large swaths of the population through public sector jobs that spur unsustainable government wage bills — as is the case in South Africa — will fall short.

Burden or Opportunity?

These indicators — while certainly not exhaustive — generally represent the forces that could drive positive adaptation to population growth. The African countries that are expected to see the most rapid population growth in the coming decades are concentrated in the Great Lakes region (including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda), the Ethiopian highlands (namely Ethiopia) and coastal West Africa (primarily Nigeria). None of these countries, however, are adequately prepared to meet the vast challenges of the population boom already well underway within their borders.

In the next part of this series, we’ll use the above set of indicators to evaluate the preparedness and impacts of population growth in major sub-Saharan African countries where the stakes will be the highest.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.