From OPEC’s oil embargo on the U.S. in the 1970s to Russia’s cutoff of gas to Western Europe last year, unsavory regimes have weaponized their control of oil and gas to pursue strategic goals.

The transition to green energy has the potential to neuter the oil and gas weapon for good. Yet we might simply be swapping one form of commodity dependence and its geopolitical baggage for another.

Wind, sun and hydrogen are free. But the equipment that transforms them into energy, stores it in batteries and transmits it needs vast quantities of minerals whose supply is more concentrated than that of oil and gas.

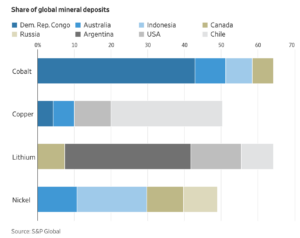

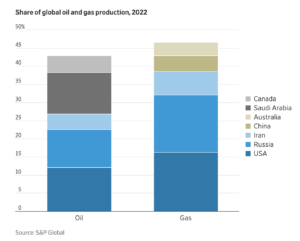

Democratic Republic of Congo has 43% of the world’s cobalt deposits, Argentina 34% of lithium, Chile 30% of copper and Indonesia 19% of nickel, according to data from S&P Global. All exceed Saudi Arabia’s 12% share of global oil production and Russia’s 16% share of natural-gas output.

For all four minerals, the five largest countries have more than half of global deposits. With oil and gas, the top five control less than half, the S&P figures show.

Downstream production is even more concentrated: China refines 70% of the world’s cobalt, 65% of its lithium and 42% of its copper, far exceeding OPEC’s share of oil output.

Western governments once welcomed China’s willingness to do this dirty work. It was the sort of interdependence globalization was supposed to foster.

Fear of interdependence

Not anymore. A new Cold War is emerging between China and Russia on one side and the U.S. and its allies on the other, and both blocs are weaponizing that interdependence. When Russia invaded Ukraine last year, the West kicked it out of the global banking system and cut off supplies of vital inputs and services. Russia in turn slashed gas supplies to Western Europe. Meanwhile, the U.S. restricted China’s access to key semiconductor technologies.

No one weaponizes interdependence more than China. It regularly bars imports and exports with countries that cross it politically, and discriminates against foreign companies to bolster its own national champions. In July it said it would restrict exports of two minerals vital for semiconductors, missile systems and solar cells.

The U.S. is scrambling now to limit its vulnerability. Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act showers subsidies on electric vehicles, batteries and renewable energy, provided the minerals involved come from the U.S. or countries with which it has a free-trade agreement and don’t come from China.

But, as S&P Global points out in a report last month, there are problems with this strategy. First, demand for these minerals is already skyrocketing, and the law will increase that demand by 12% to 15% by 2035. U.S. consumption of nickel, cobalt and lithium, used in batteries and other green technologies, will grow 23-fold by 2035, it projects. Consumption of copper, ubiquitous in power generation and transmission equipment, will double.

This, S&P concludes, will make the U.S. ever more reliant on imports that will be hard to source from free-trade partners alone, and without China. For example, in 2035, non-free-trade partners will account for 90% of global cobalt production, most of it in Democratic Republic of Congo, which exports 70% of its production to China.

These minerals aren’t actually in short supply. The U.S. alone boasts copper deposits equivalent to 20 years’ worth of its own demand, S&P notes. The problem is accessing it; the firm estimates it takes 15 years on average for a mine to go from discovery to production.

The U.S. is particularly slow: Permitting alone takes seven to 10 years, compared with two to three in Australia and Canada. Refining economics are even more challenging, said Aurian de La Noue, consulting director at S&P Commodity Insights. A copper refinery or smelter hasn’t been built in the U.S. since the 1970s, he said.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, western oil companies saw their operations nationalized by host countries. Today, resource nationalism is once again spreading. Indonesia is restricting exports of nickel ore to nurture domestic refining, and Chile is partially nationalizing its lithium mines.

Nonetheless, the geopolitics of energy in the next era will be very different from the last: energy minerals will never be weaponized as effectively as oil and gas were.

Minerals won’t have the influence oil did

Oil was in some ways unique. Easier to transport and store than wood or coal and far more efficient, oil lent itself naturally to international trade—and efforts to control that trade. Its critical role in transportation, including for army trucks, tanks, aircraft and warships, made its availability a matter of national survival, influencing the course of both world wars.

By contrast, energy minerals aren’t fuel. Deprived of some critical mineral, “the cost of EVs would go up, it would be harder to do an offshore wind project, but nobody is going to be standing in line to fill up their car with copper,” Daniel Yergin, an energy historian and vice chairman of S&P, said.

Export restrictions or attempts to form an OPEC-like cartel would in time elevate prices and spur the hunt for alternatives, much as higher oil prices in the 1970s spurred production in the North Sea and Alaska’s North Slope. A recently discovered lithium deposit in a volcanic crater along the Oregon-Nevada border could be the world’s largest, according to the magazine Chemistry World. Permitting delays would shrink in an emergency. After Russia cut gas shipments, Germany built a liquefied national gas terminal in less than a year, a project that normally takes five years.

Besides geographic diversification, renewable energy benefits from technological diversification. De La Noue notes that copper competes with aluminum in electrical wiring, while lithium, nickel and cobalt all compete with one another in battery chemistry. Innovators are working on sodium-ion and iron-air batteries that use no lithium.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to the future weaponization of energy is that we are entering an era of unprecedented variety. The data site Our World In Data notes that until the 1900s almost all energy came from coal and biomass, such as wood. Over the last century, those were joined by oil and gas. With the growth of nuclear, hydro, wind, solar and, in time, hydrogen and biofuels, the world’s energy supply will be more diversified than at any time in history.

“Diversification is the central precept of energy security,” Yergin said. In his book “The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power,” he quotes Winston Churchill on his pursuit of secure fuel supply for the Royal Navy in World War I: “Safety and certainty in oil lie in variety, and variety alone.”