February 22nd, 2023

Via Geopolitical Futures, commentary on Chinese firms’ ability to give La Paz its best chance to capitalize on the green transition.

The green energy transition is driving a global race for lithium. Countries sitting on large deposits of “white gold” suddenly find themselves with an exceptional opportunity. The prime example is Bolivia, home to the world’s largest deposits of lithium. The government in La Paz hopes this bounty will lift the country toward a more prosperous and equitable future. However, the window presented by the surge in green investment will not last forever. Facing a make-or-break moment, Bolivia has started to reform its lithium strategy and is partnering with China.

Old and New Challenges

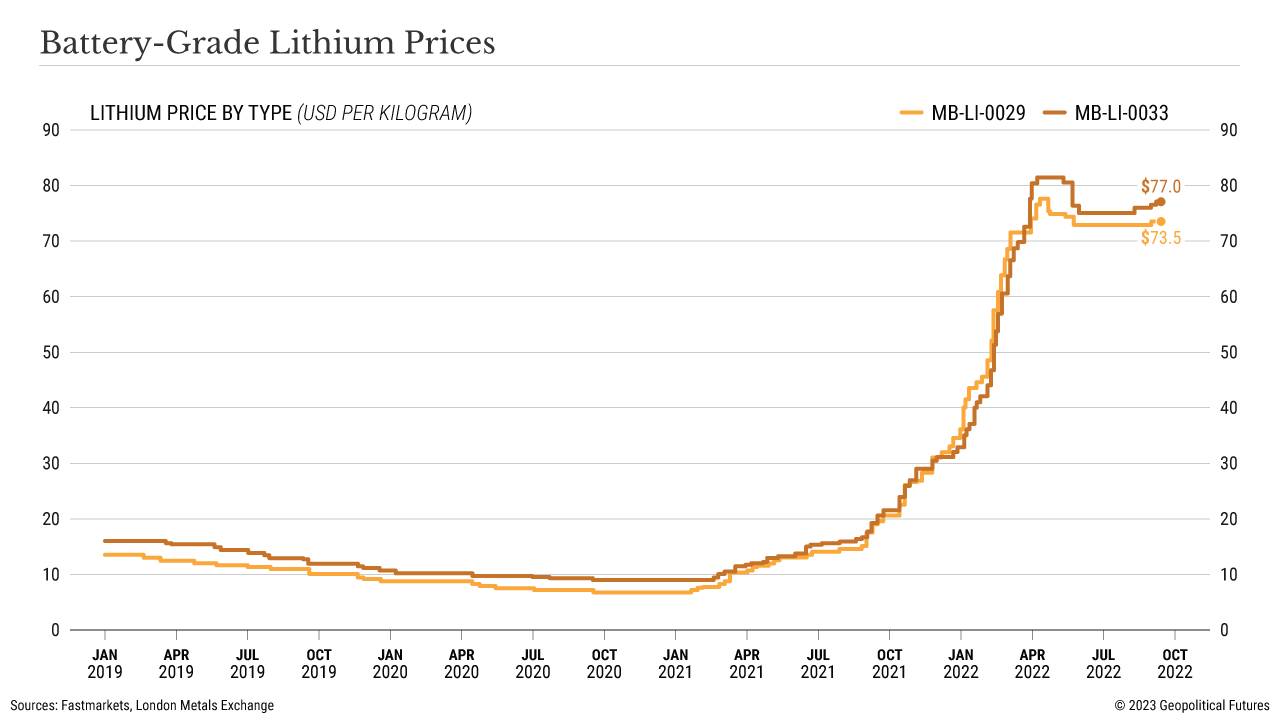

Lithium is a critical input in rechargeable batteries found in day-to-day items like laptops, cellphones and electric vehicles. It also has applications for storing hydrogen for use as a fuel and making alloys for aircraft. States’ intensifying focus on the green transition pushed up global consumption of lithium by 41 percent in 2022, to an estimated 134,000 tons from 95,000 tons in 2021. The primary driver is the EV market, specifically its need for lithium-ion batteries. As a result, lithium hydroxide and carbonate prices on the London Metals Exchange surged in December and now sit at $76,200 per ton, more than 10 times the price just two years earlier.

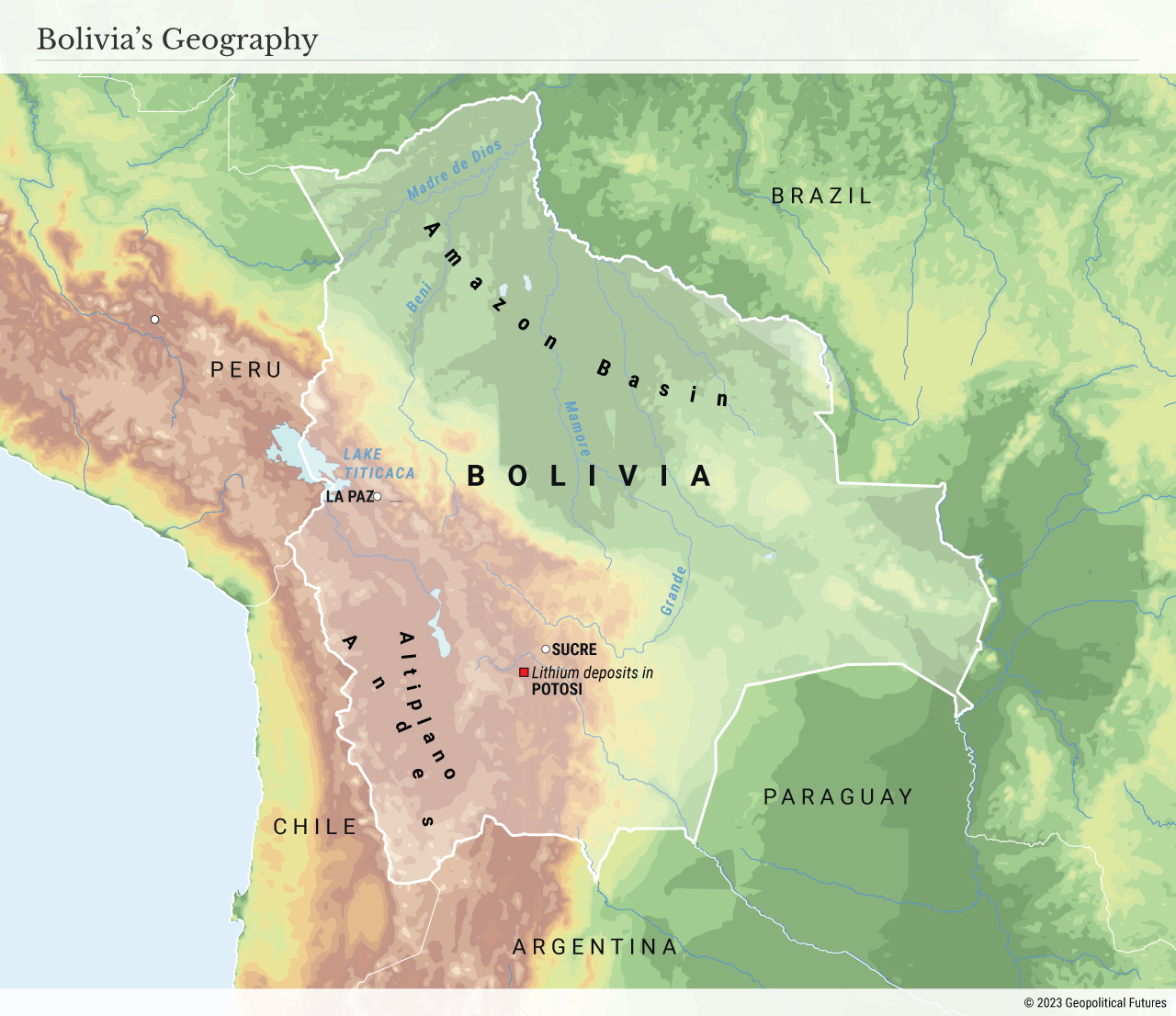

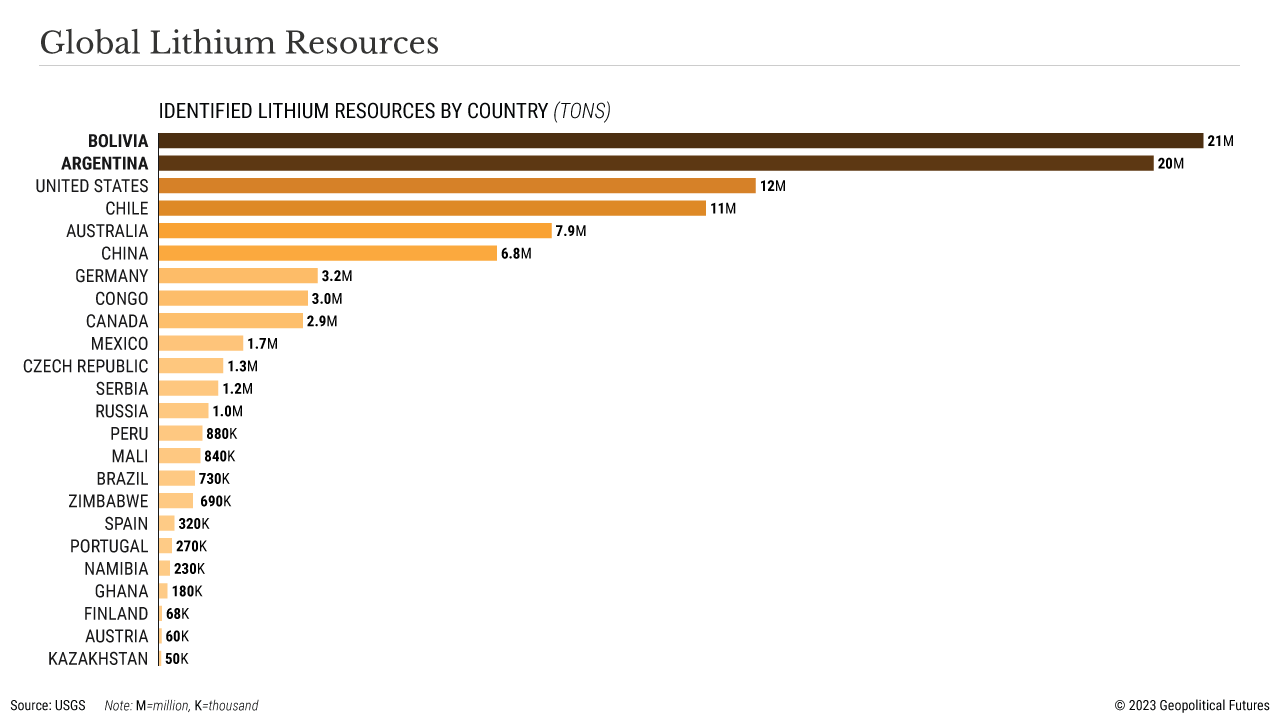

On paper, Bolivia is uniquely positioned to capitalize on the lithium craze. Three lithium salt flats – Uyuni, Coipasa and Pastos Grande – in the country’s southwest hold 21 million tons across an area nearly the size of Connecticut, according to a 2022 U.S. Geological Survey report. This makes Bolivia the largest source of the world’s estimated 89 million tons of lithium.

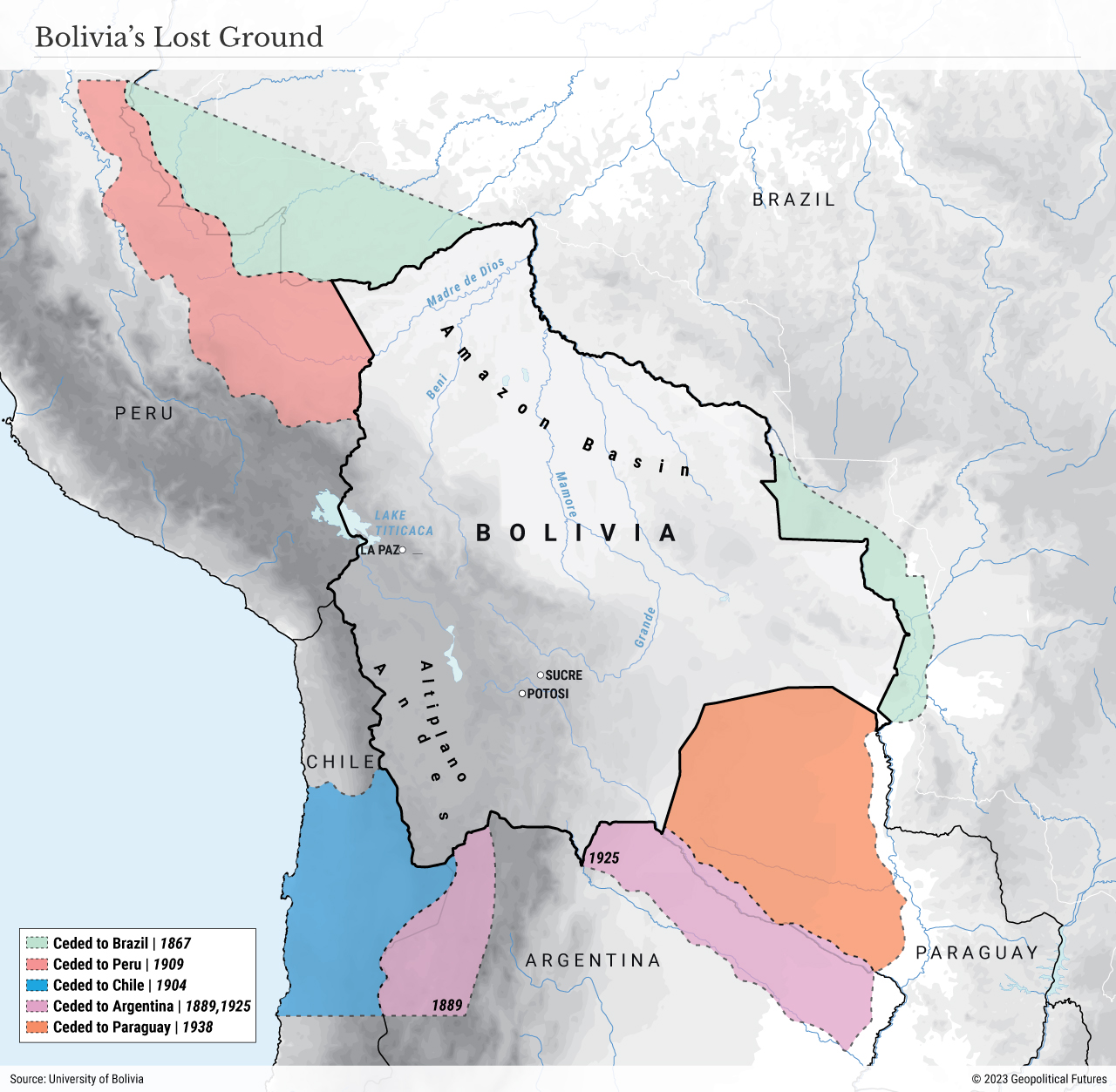

But although Bolivia has massive lithium potential, it also has a long history of government interference in natural resource extraction. Much of this can be traced back to colonialism and the country’s loss of land in the early days of independence. During the colonial era, the city of Potosi was a hub for silver mining. The Spanish forced indigenous communities to labor in the mines and shipped the silver directly to Spain. Naturally, La Paz and indigenous communities are determined to avoid repeating this experience. Further, after Bolivia split from Peru in 1839 it lost nearly half its territory to neighbors, including areas with nitrate deposits, rubber trees and potentially oil. As a result, Bolivia is extremely protective of its natural resources. In the past, it has nationalized its hydrocarbons, lithium tin, silver, electricity and telecommunications, among others.

However, Bolivia’s state-run companies have struggled to turn its resource wealth into economic development. It primarily extracts lithium via evaporation ponds, a technique from the 1960s. Because of the inefficiencies of the process, the government recovers at best about 40 percent of its lithium. The result has been underwhelming: In the past five years, Bolivia produced just 1,400 tons of lithium. For reference, 2022 global supply totaled 600,000 tons.

The risk for Bolivia is that the demand boom and soaring prices will not last long enough for it to get its supplies to market. Industry estimates say it will take up to a decade for lithium supply to catch up with demand, at which point prices are expected to stabilize. Additionally, scientists are already hunting for the next transformative technology in energy storage, from recycling lithium to tapping into the battery potential of bromine and graphite. It takes approximately 5-10 years for new mines to come online and 1-2 years to build battery factories. This means Bolivia has a narrow and closing window to modernize its lithium production, and this assumes no major disruptions, such as a drastic decline in Chinese demand.

La Paz must overcome several challenges to reach its lithium output potential. First, it needs access to the latest technology to make production more efficient and cost-effective. It is faster and easier to import these insights from foreign companies than it is to develop them domestically. Second, it needs to find skilled labor. A well-established oil and gas industry could prove useful, as the skills are generally transferrable. Finally, and most difficult, Bolivia must overcome political infighting and indigenous unrest to establish a regulatory framework that investors trust.

To address these challenges, Bolivia abandoned plans to restrict lithium production to national firms. Instead, it copied its oil and gas strategy, where the government must own at least 51 percent of a given project, with the rest open to foreign firms. Opening to foreign competition gives Bolivia access to the latest technology and reduces financial risk for Bolivia, which spent an estimated $1.2 billion on developing its lithium over the past decade with little to show for it.

Chinese Partnership

Bolivia is betting on China to bring about its lithium transformation. In January, Bolivia’s state-run lithium company Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLP) signed a deal with Chinese conglomerate CBC worth more than $1 billion. CBC comprises Beijing’s lithium powerhouses: CATL, the world’s leading lithium battery maker; BRUNP, the leader of lithium battery recycling; and CMOC, the premier producer of a variety of minerals. The agreement calls for the construction of a direct extraction of lithium plant in Potosi and another in Oruro. (YLP also plans to open a lithium carbonate facility this year with the capacity to produce 15,000 tons annually.) Direct extraction of lithium, or DEL, is the latest extraction technology. It is both cleaner and more efficient than the process Bolivia currently uses. The Chinese conglomerate will assume all the financial risk for the first six months of engineering and feasibility studies, as well as production projections.

For La Paz, partnering with Beijing was the obvious choice. Chinese companies face fewer government limits on their activities and thus can move quickly on financing, scientific studies and due diligence. Chinese firms are also comfortable operating in areas with opaque regulatory frameworks and intrusive governments. And they are accustomed to weathering indigenous resistance to resource extraction, as evidenced by China’s operations at Las Bombas in Peru. Finally, China can greatly support Bolivia’s ambition to move up the lithium-based export value chain. China is a major supplier of anodes and cathodes, which Bolivia will need to become a battery producer.

For Bolivia and China, it’s a win-win. Bolivia gets funding and technology, while China gets access to and influence over approximately one-fifth of the world’s lithium reserves. At the same time, the partnership is a setback for Western efforts to bolster their own green industrial capabilities and cut reliance on China. Western investors initially showed interest in Bolivia’s lithium deposits but were deterred by the nationalization risk, political instability and the logistical complexities of exporting the metal from a landlocked country. The U.S. appears to have accepted that China will control about half the world’s lithium markets. So long as there are other areas for the U.S. and partners to compete for supply, they will accept La Paz’s alignment with Beijing and focus their efforts on less risky locales.

Bolivia’s government set a goal of producing its own lithium-ion batteries by 2025. Experts in Potosi predict it will be more like 2030. Either timeline is ambitious given Bolivia’s starting point and the scale of the competition. Partnering with China offers no guarantees, but it does give Bolivia its best shot to cash in on its lithium.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.