May 30th, 2023

Courtesy of Nikkei Asia, a report on the Pinglu Canal in southern China which is set to reshape the movement of goods in the region when it is completed in a few years. The $10 billion project highlights Beijing’s shifting focus toward maritime connectivity for its Belt and Road Initiative, observers say. But as the U.S. and its allies move to “de-risk” from China and Beijing aims to boost its connections with Southeast Asia, geopolitics is adding an element of urgency to the endeavor.

The steady thunder of dump trucks breaks the serenity of what were once forested hills in the southern Chinese region of Guangxi. They carry mounds of earth excavated to build an enormous canal, with locks capable of accommodating 5,000-tonne cargo ships.

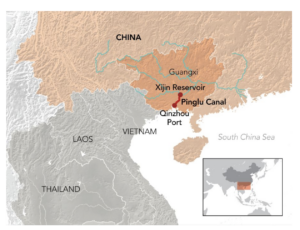

The 72.7 billion yuan ($10.3 billion) Pinglu Canal will stretch over 134 kilometers from the Xijin Reservoir, near Guangxi’s capital city of Nanning, to the port of Qinzhou in the south, complementing existing highways and railways to move goods.

All told, officials say an estimated 340 million cubic meters of dirt and rocks — three times what was excavated to build China’s Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest hydroelectric plant — will be cleared away.

“Work is being carried out on a 24-hour basis” to meet the completion deadline of 2026, Li Xiaoxiang, an official at the construction site, told Nikkei Asia during a recent tour organized and supervised by Guangxi’s foreign affairs office.

Launched last year, the project highlights Beijing’s shifting focus toward enhancing maritime connectivity for its Belt and Road Initiative, as opposed to land routes, observers say. “That’s quite new,” said Yang Jiang, an expert on China’s politics and economy at the Danish Institute for International Studies, noting the canal was conceived in a 2019 plan to construct a strong transport country. “A lot of effort so far has been on railway” infrastructure.

Officials say that when completed, the canal will shorten the shipping distance from inland river systems to the sea by 560 km, versus going through Guangzhou. Li claimed this would save up to 5.2 billion yuan annually.

By creating a convenient and economical gateway close to Southeast Asia, the waterway also promises to help rev up industries in Guangxi and other parts of relatively less-developed western China. But geopolitics may be adding an element of urgency to the endeavor.

Just as the U.S. and Western allies are determined to “de-risk” from China, as illustrated at the Group of Seven summit in Hiroshima in mid-May, Beijing is keen to reduce its own trade dependencies. Both sides “have the same fear,” analysts wrote in a report published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in March: “that the other side will suddenly weaponize trade flows — cut off imports or exports — in the name of security.”

“Trying to get ahead of that, each is now attempting to diversify.”

The Pinglu Canal is aimed at boosting already growing trade with the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, all of which are grouped with China under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free trade framework, officials said. Even now, ASEAN and China are each other’s largest trade partners, with two-way trade rising 52% from 2019 to 2022 — exceeding the 20% increase with the European Union.

Besides reducing China’s reliance on trade with the West, some say doing more business with Southeast Asia could soften the animosity between Beijing and several governments in the region.

“A stronger relationship between China and some ASEAN countries benefits both, since they need such cooperation to blunt the sharpness of their territorial disagreements in the Spratly and Paracel islands,” said Phar Kim Beng, CEO of Malaysian consultancy Strategic Pan Indo-Pacific Arena (SPIPA), referring to territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

Yang at the Danish Institute said the lessons of the pandemic further spurred authorities to beef up shipping infrastructure. China’s COVID-19 lockdowns caused severe supply-chain interruptions as logistics were concentrated in key ports on the country’s eastern coast.

“In view of China’s difficulties handling global logistics during COVID, there is obviously a need to strengthen some of the ports in China so that it doesn’t rely on bigger ports in Shanghai,” Yang said.

Indeed, the canal is only part of an ambitious effort to create an efficient land-sea corridor.

About 40 km away from the construction site, a parade of driverless trucks moves 20-foot shipping containers at the Qinzhou Automated Container Terminal. They roll toward a quay, where computer-operated cranes pick up the containers and shift them over to a berthed cargo ship.

“Welcome to our intelligent port,” said an official at the terminal, operated by state-owned Beibu Gulf Port Group. The official explained that the facility is the product of 22 months of upgrade work completed last June.

Guangxi government officials say the emerging corridor has already accelerated logistics — speeding up shipments from Chongqing in western China to Singapore to seven days, from 22.

Even with such improvements, some experts caution that the full economic benefits of the canal and high-tech port infrastructure will not be automatically unlocked.

“The construction of efficient infrastructure is a welcomed development, however it cannot by itself create trade synergies where they don’t exist, nor can it create competitive industries in ASEAN capable of producing products that Chinese importers will demand,” said Stephen Olson, senior research fellow at Singapore’s Hinrich Foundation, suggesting there may be certain limits to the growth of trade with the Southeast Asian bloc.

He added that “China’s economy is far larger than any single economy in ASEAN, and that creates leverage that can sometimes result in unbalanced and unsustainable trade relationships.”

Olson also expressed skepticism about efforts by both the U.S. and China to pull ASEAN countries closer to their side. “For most countries in ASEAN, their national interests are best served by sitting on the fence and maintaining robust economic and strategic ties with both,” he said.

There are concerns about costs as well — environmental and financial.

When asked about the impact on ecosystems from clearing such a huge swath of land for the canal, a project official vowed that “we will also construct conservation havens to safeguard the ecology” but did not go into details.

A study published last year by the Transport Planning and Research Institute, under China’s Ministry of Transport, did flag a range of potential side effects from the canal — including isolation or destruction of natural habitats, changes to the area’s ecology, a reduction in vegetation, and dust or other pollution from passing vessels. Still, the authors argued that depending on the route, the risks should be “controllable,” while noting that “abundant wetland environments” could be created to mitigate the impact.

The estimated $10.3 billion bill for the canal project, meanwhile, comes amid greater scrutiny of Chinese local governments’ fiscal health now that pandemic-related social restrictions have been lifted, and with the property sector going through a painful slowdown.

The canal project is backed by state institutions in Guangxi, including Guangxi Beibu Gulf Investment Group, according to company data search portal Aiqicha.com. The group in December was assigned to a Baa3 rating in its first assessment by Moody’s. The rating, Moody’s lowest investment grade, was buoyed by the backing of the Guangxi government, though the agency noted the group’s “fast debt growth related to its investments in public policy projects.”

That aside, both foreign and local manufacturers in Qinzhou say they are beginning to feel the effects of the upgraded port facilities, as well as RCEP. The trade deal, also signed by Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, took effect last year. It eliminates 90% of tariffs on goods traded between the signatories.

“Tax clearance has been cut from three days to just one-to-two minutes,” said Zhou Ju, an official at Asia Pulp and Paper in Qinzhou, backed by Indonesian conglomerate Sinar Mas Group. Zhou attributed this to the certificate of origin — export documentation available online under RCEP.

Officials insist the Pinglu Canal promises to help China reap even greater gains from RCEP. Phar at Malaysia’s SPIPA suggested there might be some public relations value to consider, with both Southeast Asian countries and the domestic population.

“Most, if not all, developing countries do need iconic projects to win the hearts and minds of the people domestically as well as abroad,” he said.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.