Five years ago, Chancay was just an ordinary tourist town about 50 miles from Peru’s capital, Lima, with its main visitor draw a faux castle-cum-theme park. Come October, Chancay will begin hosting visitors of a different kind: the world’s largest mega ships, and even, potentially, Chinese President Xi Jinping.

That’s when a new $3.5 billion port controlled by China’s COSCO Shipping is set to be inaugurated, a project poised to uplift China’s relationship with both Peru and the broader South America region.

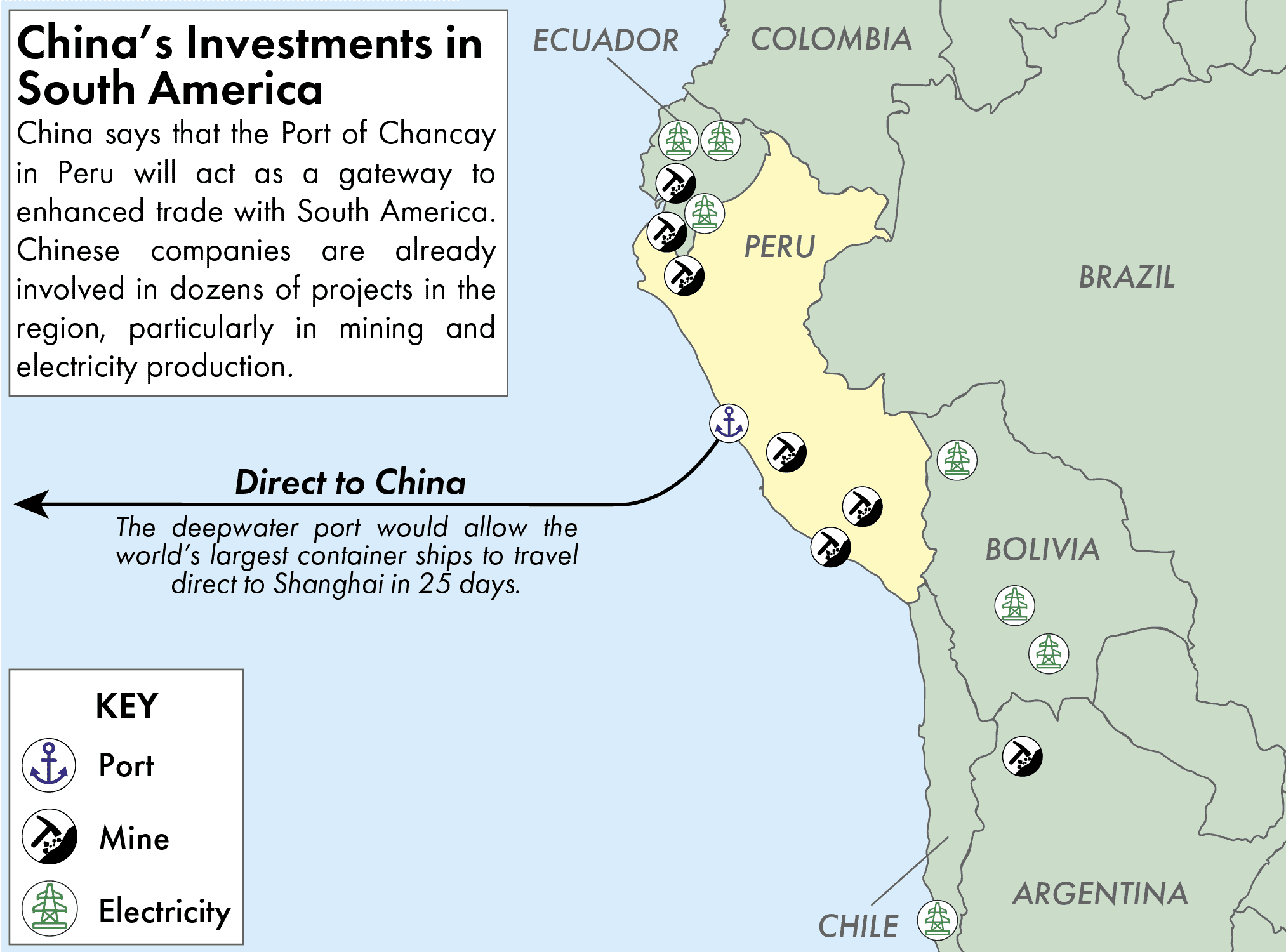

Chinese companies have long invested in maritime infrastructure in places like Brazil, but with an intractable obstacle: the ports connect to the ‘wrong’ ocean. Facing the Pacific, the new Port of Chancay will slash shipping times from South America’s western coast to China by as much as a week and a half, cementing it as a commercial hub for trade in a part of the world increasingly eyed by Chinese companies. Xi could cut the ribbon while in town for the 2024 APEC summit later this year, according to Peru’s foreign minister.

The port is in one sense a textbook project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which, more than a decade in, has channeled over $1 trillion towards new infrastructure projects around the world. Investments in far flung, resource-rich regions have helped feed the insatiable appetite of China’s consumer and manufacturing sectors.

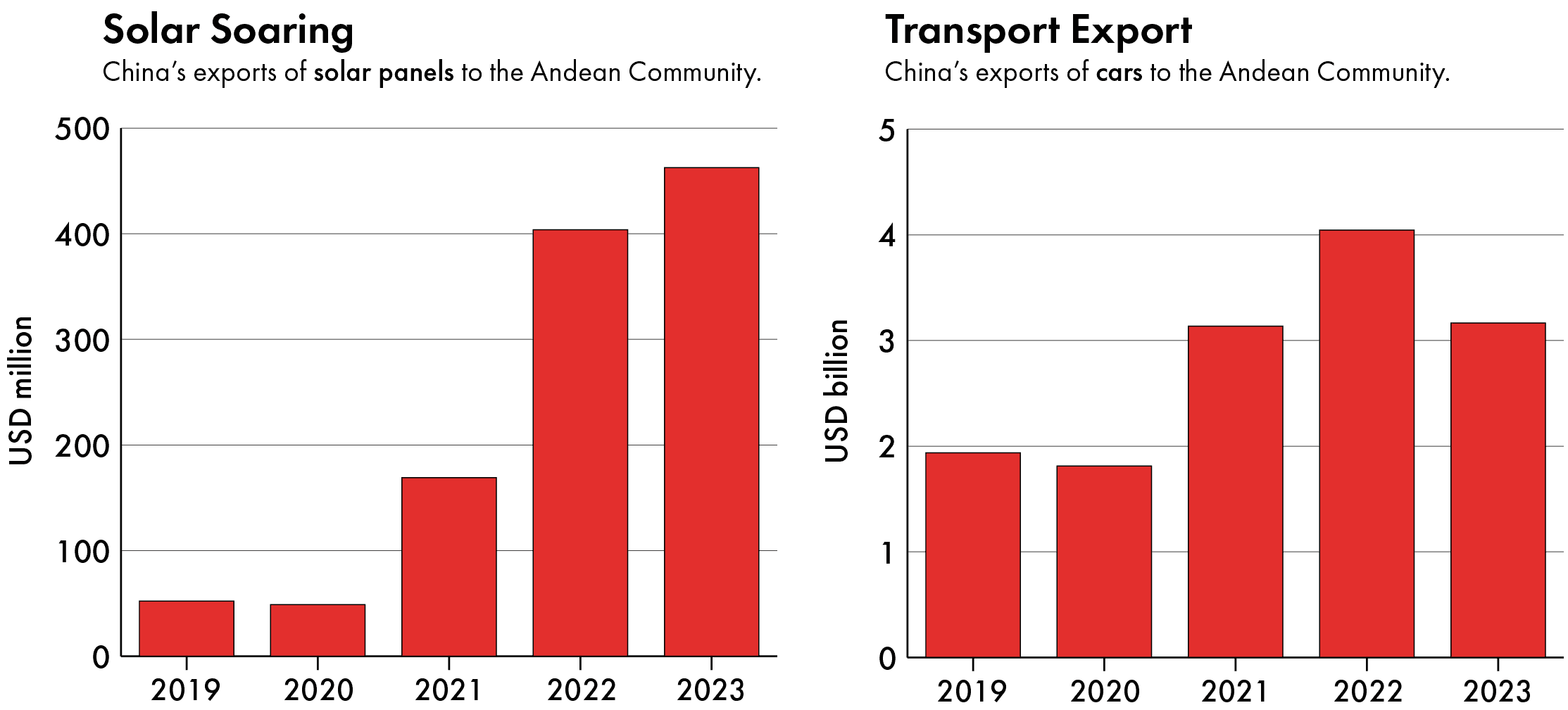

But as China’s economy slows and it reckons with new challenges like mounting industrial overcapacity, its priorities with BRI partners are changing. Long coveted for its extractable resources from copper to lithium, South America is now a prime destination for Chinese outputs, from energy resources to electric vehicles.

Earlier this month, for instance, electric vehicle (EV) giant BYD announced a deal to supply Uber with 100,000 cars, which will be rolled out first in Latin America and Europe. Earlier this year, China Southern Power Grid closed a $2.9 billion deal for two Peruvian assets, meaning Chinese companies now control 100 percent of Peru’s electricity transmission system.

For Washington, the deepening bilateral relationship raises alarms. While U.S. foreign direct investment into Latin America still dwarfs China’s contribution, the U.S. military sees a threat in the concentration of investment from China’s national champions in a region Washington has long considered within its sphere of influence.

“The PRC is playing the ‘long game’ with its development of dual-use sites and facilities throughout the region,” General Laura Richardson, commander of the U.S. Southern Command, warned Congress in March. “The PRC messages its investments as peaceful, but in fact, many serve as points of future multi-domain access for the PLA and strategic naval chokepoints.”

In July, senators Mark Kelly (D-AZ), Marco Rubio (R-FL), and Rick Scott (R-FL) introduced the Strategic Port Reporting Act, a bipartisan bill that would require the Defense Department devise a strategy to counter China’s growing influence at key global ports.

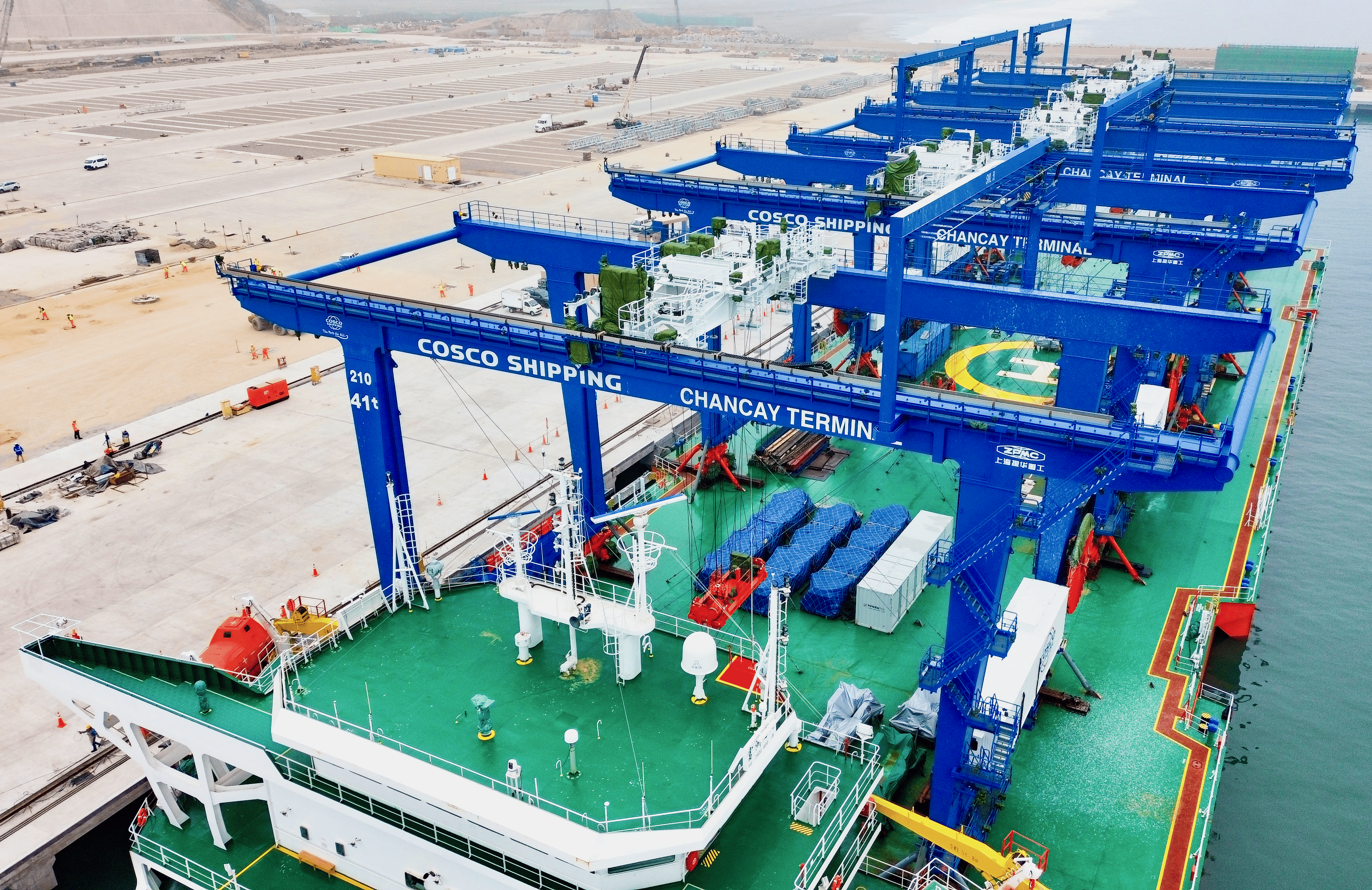

Driving the project in Chancay is state-owned COSCO Shipping, which owns a 60 percent stake in the port as well as exclusive operating rights.

“COSCO is not primarily a port operator, it’s a shipping company. It’s hyping the port as a logistics system,” says Isaac Kardon, an expert on China’s maritime strategy at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Chancay represents a major new hub for Chinese trade with Latin America. There are high expectations that this will knit together the region in some way.”

An armada of Chinese exporters could benefit from the streamlined trade route. Solar panel manufacturers have found a booming market in the Andean Community, a free trade area encompassing Peru and neighbors Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador, where sales have soared 900 percent over the last five years, according to data compiled by the International Trade Centre. Chinese exports to Brazil, which will also benefit from overland connections to Chancay’s port, have risen 50 percent over the same period.

The concern is that such Chinese initiatives could come at the expense of American influence. Built over a natural deepwater harbor, Chancay’s port is the first in the region to support “post-Panamax” ships — modern vessels so colossal that they’ve outgrown the Panama Canal. With 15 berths, the size and capacity of Chancay’s port could draw activity away from competitor ports from Colombia to Chile, concentrating economic activity and potential intelligence in the hands of its operator.

That outcome would benefit not just COSCO, but an array of other Chinese companies that gain from the collateral benefits of Belt and Road projects, from power companies to railway builders. “COSCO pursues a model of integrated trade infrastructure overall,” says Kardon. “The whole thing is supposed to generate a friendly ecosystem that facilitates a range of commercial activities. It encourages Chinese enterprises to develop business arrangements.”

Peru’s prime minister has proposed reviving plans for a long-discussed railway line through Bolivia and to Brazil; president Dina Boluarte paid a visit to China Railway Construction on her state visit to China. In June, Boluarte also explicitly cited Chancay port in her pitch to BYD to build an EV assembly plant in the country, pledging zero tariffs on imports or exports.

COSCO has also struck a deal with Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries (ZPMC), a Chinese manufacturer of ship-to-shore cranes. The U.S. says these highly automated heavy lifters are an intelligence risk, and the Biden administration is spending $20 billion to rip and replace ZPMC cranes from U.S. ports.

“When you have a scanner or a crane that is able to gather specific data on port calls, how many containers come in, and where they’re from, all this information is extremely important in a potential conflict,” says Leland Lazarus, an expert on China-Latin America relations with Florida International University.

Lazarus cautions against making alarmist assumptions about China’s intentions with the port. There are no signs that China intends to militarize it, for example, although officials have not forbidden Chinese naval vessels from making stops there.

“COSCO has a higher propensity of hosting [People’s Liberation Army] vessels than any other Chinese firms,” says Kardon. “While quite far from a Chinese base, [Chancay] is certainly closer to a place that the PLA would consider a friendly port of call.”

The Peruvian government is determined to press on with the project. Despite political instability since the deal was signed in 2019, the project has retained support from the country’s last six presidents in as many years.

“Deepening relations with China has cross party support in Peru,” says Martin Cassinelli, a researcher with the Atlantic Council’s Latin America Center. “But it is important not to understand it as an ideological alignment, but as support for the economic opportunities that China offers.”

But as Peru goes all in on deepening relations with China, some experts warn that it is exposing itself to potential coercion. A legal dispute in March showed the kind of leverage China has to force its way. After Peru’s port authority filed a lawsuit requesting the annulment of a deal that gave COSCO exclusive operating rights over the port, COSCO threatened to pull out from the near-completed project. Peru’s legislature rewrote the law to accommodate the company’s demands.