December 8th, 2012

Via newgeography, an interesting look at China’s second tier cities:

Recent media attention has focused on a slowdown in China. The actual state of play in China that should be watched, though, is rather different. While residents of first and second-tier cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen can still be seen holding Louis Vuitton bags and iPhones, a significantly larger, yet less individually affluent, market has begun to rise within the country. It is within this terrain of lower-tier cities that China’s breakneck growth is now being demonstrated. It’s still a bit too early for these residents to be showing off designer handbags and Apple gimmickry, yet a solid and highly-sustainable growth wave is happening across China’s fourth, fifth, and sixth-tier cities in the central and western regions.

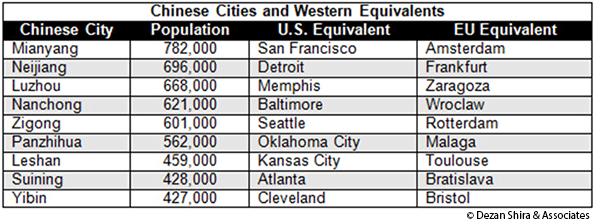

Here are some examples, in terms of rough population equivalents:

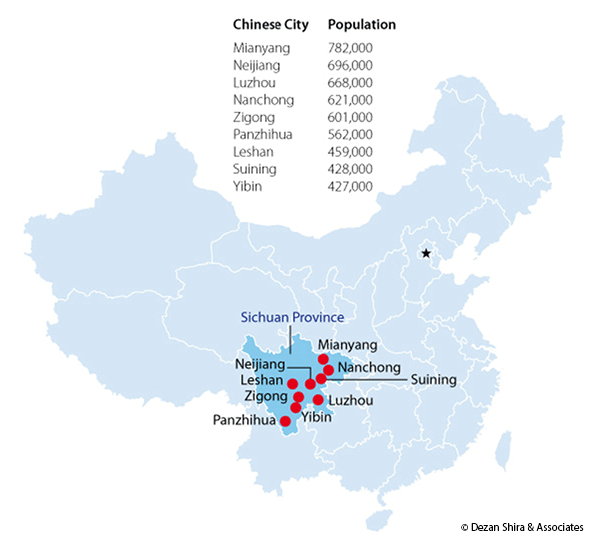

While many readers are familiar with most of these American and European cities, hardly any know their Chinese counterparts. And all of the Chinese cities in the chart above are in just one province – Sichuan.

When one factors in Shanxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, and Jiangxi in Central China, and Gansu, Guizhou, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Yunnan and Xinjiang in West China, the sheer vastness of China’s own emerging markets becomes apparent. There are some 500 cities across the region with populations similar to those listed above.

What’s happening in these lower-tier Chinese cities? The local populations are now becoming more affluent. Crucially, this is a phenomenon driven by state policy, as Beijing wishes to reduce the national East-West income gap and raise the standards of wealth across the country. It has been doing this by embarking on an aggressive policy of increasing minimum wages on a national basis, and especially so in the hinterlands. That is having the effect of increasing disposable income levels, and these consumers are now upgrading purchases from previously purely Chinese brands towards increasing levels of Western products.

This includes the use of fast-food chains such as McDonald’s, KFC and Starbucks; massive multi-brand retailers such as Wal-Mart, Carrefour, and others that are also making inroads into these further-flung destinations. The Louis Vuitton bag may still be the preserve of China’s super wealthy in Shanghai, but in cities such as Mianyang, youths are trading up their cheap Chinese sneakers for Nikes, and looking to acquire Levis instead of the local jeans. With these consumer patterns being duplicated across the rest of China’s inland provinces, the result is little less than a revolutionary ‘upgradation’ of inland consumer power.

The other markets in China worth keeping an eye on are those located along China’s borders. I wrote about Urumqi as a springboard for Central Asia recently. Developments elsewhere in Asia dictate that other border areas will also begin to experience significant growth, not least because of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN’s) full free trade agreement that is set to abolish tariffs between member nations by 2015.

ASEAN includes countries that rub up alongside China’s southwest border, such as Myanmar, Vietnam and Cambodia, and adds to that countries including Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand, while to the south of China (and Guangdong Province in particular), ASEAN nations such Indonesia and the Philippines provide easy access. Why is this important? Because China has its own free trade agreement with ASEAN, and those 0 percent export tariffs among ASEAN nations are largely duplicated within China’s own agreements with the bloc.

That means cities such as Jinghong and Luxi in Yunnan are also poised to become trade hubs. Jinghong, with a population of 520,000 is equivalent in size to Tuscon, Arizona and Sheffield in the United Kingdom, and borders Vietnam, while Luxi borders Myanmar, and with a population of 350,000 is similar in size to Tampa, Florida or Bilbao.

Demand from the West does continue to remain sluggish, and inattentive analysts like to point to a drop in national GDP growth rates as evidence of some sort of cataclysmic event concerning development in China. That is only one, rather blinkered way of assessing the situation. Since China’s annual growth has moved briskly along at 10 percent for much of the past 15 years, a deviation from that is greeted by analytical soothsayers with cries of doom. Yet China’s 10 percent growth was never capable of being sustained, as each successive year of double-digit growth has, naturally, expanded the base to the point where it is now the world’s second-largest economy.

China’s national GDP rates have slipped to between seven and eight percent, and it may be experiencing a “slowdown” to single-digit GDP growth when measured on a national basis. But the real story is the continued fast-paced development of wealth, disposable income, and increasing consumerism in China’s own emerging markets and the fourth, fifth and sixth-tier cities that help make up this this gigantic consumer sector. The challenge for the foreign investor will now be to reach out and go after these less glamorous locations.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.