April 10th, 2024

Courtesy of The Financial Times, an article on China’s Tianqi’s $4bn bet on Chile’s lithium which is at risk of backfiring:

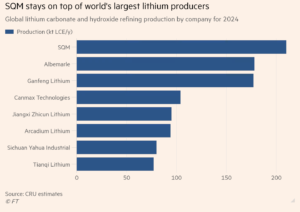

When China’s Tianqi Lithium paid $4bn in 2018 to become the second-largest shareholder in Chile’s SQM, it was making a gamble to gain a strategic foothold in one of the world’s top lithium reserves as demand soared for the metal at the heart of the electric vehicle revolution.

But Tianqi’s investment to solidify its position in Latin America, home to the “lithium triangle” of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, is in jeopardy as the Chilean government works to exert more control over the vast salt flats of the Atacama Desert, where SQM produces one-fifth of the world’s lithium.

SQM has entered a preliminary agreement to form a joint venture with state-owned copper producer Codelco, a deal that would fulfil President Gabriel Boric’s mandate that strategic lithium projects should begin as or shift to public-private partnerships. The joint venture risks diluting Tianqi’s current interests in SQM’s lithium business, and cutting it out of further possible access to the quality lithium resources.

“I assume Tianqi’s hope when it stepped into SQM was to one day run the lithium business by buying control,” said Daniel Jimenez, founder of lithium consultancy iLiMarkets who previously worked at SQM for 28 years. “With the agreement between SQM and Codelco, that dream vanishes.”

Tianqi’s trouble in Chile comes as countries around the world are taking back control of commodities critical for the green transition, including lithium, copper, cobalt and nickel — with prices set to rebound from depressed levels as demand soars.

Indonesia has banned the export of nickel ore, requiring processing facilities to be built locally, while Zimbabwe and Namibia have banned exports of raw lithium. The Democratic Republic of Congo, a cobalt powerhouse, is reviewing the contracts of all producers to negotiate a fairer share of revenues for the country.

Hong Kong-listed shares of China’s second-largest lithium producer have fallen 17 per cent over the past year under pressure from plunging prices of the metal. Tianqi posted a 70 per cent net profit fall year on year to Rmb7.23bn ($1bn) in 2023.

SQM and Codelco reached a preliminary deal in December under which SQM’s lithium business would be carved out into a joint venture with Codelco, which will hold a 50 per cent stake plus one share.

The joint venture would start next year and carry out SQM’s contracts with Chile’s government mining agency Corfo until 2030, when they are due to expire. The company will then take on fresh contracts until 2060.

If the deal goes ahead, Tianqi will hold a diluted stake in the lithium joint venture, limiting its influence on the company.

“SQM is effectively signing away future control of its [lithium] distributions” beyond 2030, said Scotiabank in a note. “Lithium cash flow and distributions to SQM will be controlled by a state-owned board, whose shareholders are the people of Chile, not Tianqi.”

Chilean funds are also worried about what happens to SQM dividends after the lithium division is split off — the unit provides the bulk of the chemical company’s revenues — as well as potentially higher taxes and wage costs under state control, according to analysts.

Tianqi is demanding a vote on the deal but the Chilean regulator ruled this year that SQM did not need to give shareholders such a vote.

“The lack of transparency and details restricts all shareholders from making an informed decision,” Tianqi chief executive Frank Ha told Chilean media last month. He added that “we are very interested in knowing what is hidden behind” the SQM-Codelco agreement. Tianqi declined to comment further.

One person familiar with the dispute said that Tianqi was in a fight to retain its influence in the new joint venture between SQM and Codelco, fearing it would be left with shares principally in a fertiliser company. SQM also produces iodine, potassium and nitrates.

“With this deal between SQM and Codelco, Tianqi is in a tight spot,” the person said. “It could be about whether they can snag a seat on the board for the new joint venture. But what it really wants is the opportunity, by whatever means, to operate in the Salar de Atacama.”

A day before an extraordinary meeting at SQM called by Tianqi in March, Xu Tieying, one of Tianqi’s three nominated board members, resigned without explanation. His resignation will trigger an election process for the entire SQM board based on Chilean rules, potentially slowing down the deal.

SQM chair Gonzalo Guerrero accused Tianqi of bad faith and wanting to use a shareholder vote to block SQM’s deal with Codelco in the Salar de Atacama in order to mount its own takeover attempt. “Are these statements in the best interest of SQM or Tianqi?” he said.

Submitting the deal to a vote would hand Tianqi a veto in effect, he said. “It is worth wondering if once the transaction is vetoed, Tianqi will not try to pursue this business opportunity for itself, misappropriating a business opportunity that belongs to SQM and all of its shareholders,” added Guerrero.

Gustavo Lagos, professor of mining engineering at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said that Tianqi’s goal to assume more control was “always optimistic” because it was unlikely to be able to buy up more shares in SQM.

Lagos said it was unlikely that Julio Ponce, SQM’s largest shareholder and former son-in-law of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, would ever sell his stake in SQM. The company is “one of Chile’s best-performing businesses” and forms the foundation of his personal wealth.

Jose Hofer, a former SQM employee now working as a commercial manager of Livista Energy, which is attempting to establish lithium refineries in Europe, said that Tianqi’s troubles were not limited to Chile. The company is also struggling to increase output at its Kwinana plant in Australia.

“It’s not a very positive panorama for them,” he said.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.