October 27th, 2013

Via The Economist, an interesting report on Indian business in Africa:

ABHIJIT SANYAL is sitting on a beach-chair watching frothy waves roll in from the Indian Ocean. He arrived in Tanzania a year ago after a career in his native India with Unilever, an Anglo-Dutch consumer-goods giant. ChemiCotex, an industrial company in Dar es Salaam, hired him as chief executive to oversee the expansion of its “tooth-and-nail business”, which dominates the Tanzanian market for dental care and metal goods.

“A lot of the challenges here are familiar to someone like me from India,” he says. “And so are the solutions.” Distribution is hampered by poor infrastructure, as is the electricity supply. Ancient and modern manufacturing processes co-exist uneasily. Most customers are middle- and upper-class; the rest are too poor.

What surprised Mr Sanyal when he arrived was how often people in Tanzania mistook him for a local. “On a new continent you expect residents to recognise you instantly as an outsider—but not here.” East and southern Africa host large populations of people from the subcontinent, mainly India. Most distributors of Samsung goods in Kenya are Indian. Many of their ancestors came as railway-workers and traders in the early 20th century. The rupee was then east Africa’s main currency. Mahatma Gandhi spent two decades in South Africa and Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first prime minister, backed African nationalist movements in the 1950s. Until 1999 India’s trade with Africa exceeded China’s. “It’s not called the Indian Ocean for nothing,” says Mr Sanyal.

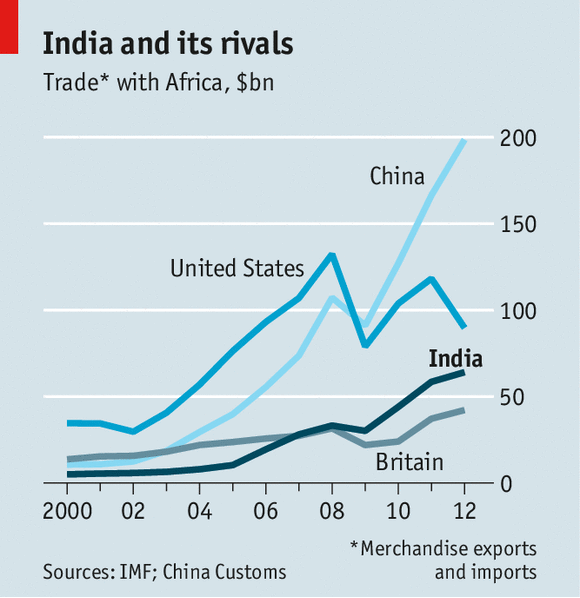

The Chinese have arrived en masse since the turn of this century and have quickly come to be seen as dominant investors. But Indians are far from cowed. A new wave is crossing the ocean, some coming alone or as salarymen, working for or with locals, even managing them. Cities such as Dar have fast-growing Indian expatriate communities. The charge is led by Indian private-sector behemoths such as Bharti Enterprises, Essar and Tata. Rather than focusing on trading goods, they increasingly invest in the continent. Bharti Airtel bought an Africa-wide mobile phone network in 2010 for $10.7 billion.

Private firms are joined by India’s state energy companies. Oil and Natural Gas Corp, India’s biggest oil explorer, bought a 10% stake in a Mozambican offshore gasfield for $2.6 billion in August. The company said the field has the “potential to become one of the world’s largest”. In June, Indian firms spent $2.5 billion on a share in a Mozambican oilfield. India is keen to ensure access to fuel supplies and raw materials for its fast-growing economy.

Agriculture is another focus. Indians have invested more than $1 billion in farms in Ethiopia. Karuturi Global from Bangalore, the world’s biggest producer of cut flowers, employs 5,000 people at a rose farm on the shores of Lake Naivasha in Kenya. They send more than 1m stems a day to Europe, which is easier to reach from Africa, especially thanks to favourable EU trade arrangements.

Nigeria is emerging as another popular stamping-ground. Its population of 170m, Africa’s biggest by far, has growing consumer demand and sits in the same time zone as Europe, which is useful for Indian call centres. Indian energy firms are bidding for parts of Nigeria’s electricity grid that are being privatised for billions of dollars. Indian drug companies are the biggest supplier of pharmaceuticals in Nigeria, with revenues growing by 35% a year.

Most Indian firms come to Africa under their own steam, but they can increasingly count on their government’s political and diplomatic heft. India’s navy takes an increasing part in international efforts to stamp out piracy in the Indian Ocean. America is supportive, not least to counter Chinese influence in Asian waters.

In many ways Africa is a test of how India intends to behave as a rising power. Unlike other continents, particularly Asia, where India is expanding its presence, Africa is a relatively open space: a new power has more freedom to chart its own course. One question often asked in Beijing and Washington, for different reasons, is how much additional legitimacy India enjoys in Africa for being a democracy.

As it strives to do business there, will it also seek to liberate politics? Tellingly, India is copying a Chinese model of investment: the provision of oodles of trade financing, the opening of lots of embassies, frequent talks with African leaders, elaborate regional summits and friendly rhetoric about the virtues of “south-south co-operation”. The Indian government has offered more than $10 billion in loan programmes to finance trade and investment by Indian companies, still far behind the financing on offer from Chinese state banks. But India’s cumbersome bureaucracy keeps tripping up its businesses. Indian financing for the Katende hydroelectric project in Congo took three years to come through, whereas China provided funding for a similar project in three months.

India has held two summits with African governments, in 2008 and 2011, and plans another next year. It is also negotiating a mechanism with South Africa for settling much of the $14 billion-a-year trade between the two countries in local currencies. India’s commerce minister, Anand Sharma, says he expects trade with Africa as a whole to rise to $100 billion in 2015, up from $70 billion today and less than $5 billion a decade ago. China’s African annual trade with Africa is worth $200 billion.

Competition between India and China in Africa is played down by both sides. Indians like to point out that Chinese historical links to the continent are much weaker than their own. Mao Zedong tried hard in the 1960s, but his descendants “stick out like a sore hand”, says a Mumbai native.

The two Asian giants certainly compete for the same energy resources and infrastructure deals, with China a pip or more ahead when it comes to the biggest contracts. But that comes at a cost for the winner. India benefits from being somewhat less prominent. The Chinese are derided by some Africans as new colonialists, propping up brutal rulers and corrupting democratic ones. Indian businesses have encountered fewer suspicions, even though they support many of the same dictators, including those in Angola, Sudan and Zimbabwe.

Indian businesses have been better at invading Chinese turf than vice versa. When selling turbines or mining ore, the Asian behemoths compete head on, yet in running hospitals or telecoms the private Indian operators have little to fear from China’s firms, which are still state-owned. They thus prove wrong a doyen of Indo-African relations, Mahatma Gandhi, who observed in the early 20th century, “The commerce between India and Africa will be of ideas and services, not of manufactured goods against raw materials after the fashion of Western exploiters.”

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.