January 6th, 2016

Via The Economist, an interesting look at Ethiopia:

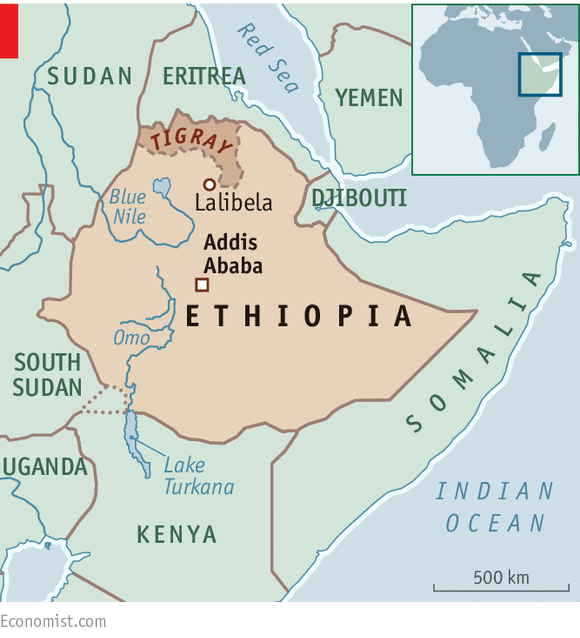

THE Ben Abeba restaurant is a spiral-shaped concrete confection perched on a mountain ridge near Lalibela, an Ethiopian town known for its labyrinth of 12th-century churches hewn out of solid rock. The view is breathtaking: as the sun goes down, a spur of the Great Rift Valley stretches out seemingly miles below in subtly changing hues of green and brown, rolling away, fold after fold, as far as the eye can see. An immense lammergeyer, or bearded vulture, floats past, showing off its russet trousers.

The staff, chivvied jovially along by an intrepid retired Scottish schoolmarm who created the restaurant a few years ago with an Ethiopian business partner, wrap yellow and white shawls around the guests against the sudden evening chill. The most popular dish is a spicy Ethiopian version of that old British staple, shepherd’s pie, with minced goat’s meat sometimes replacing lamb. Ben Abeba, whose name is a fusion of Scots and Amharic, Ethiopia’s main language, is widely considered the best eatery in the highlands surrounding Lalibela, nearly 700km (435 miles) north of Addis Ababa, the capital, by bumpy road.

Yet the obstacles faced by its owners illustrate what go-ahead locals and foreign investors must overcome if Ethiopia is to take off. Electricity is sporadic. Refrigeration is ropey, so fish is off the menu. So are butter and cheese; Susan Aitchison, the restaurant’s resilient co-owner, won’t use the local milk, as it is unpasteurised. Honey, mangoes, guava, papaya and avocados, grown on farmland leased to the enterprising pair, who have planted 30,000 trees, are delicious. All land belongs to the state, so it cannot be used as collateral for borrowing, which is one reason why commercial farming has yet to reach Lalibela. Consequently supplies of culinary basics are spotty. Local chickens are too scrawny. The government will not yet allow retailers such as South Africa’s Shoprite or Kenya’s Nakumatt to set up in Ethiopia, let alone in Lalibela, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Bookings at Ben Abeba are tricky to take, since the internet and mobile-phone service are patchy. Credit cards work “about half the time”, says Ms Aitchison. Imports for such essentials as kitchen spares are often held up at the airport, where tariffs are sky-high: a recent batch of T-shirts with logos for the staff ended up costing three times its original price. Wine, even the excellent local stuff, is sometimes unavailable, because transport from Addis, two days’ drive away, is irregular and private haulage minimal. The postal service barely works. Fuel at Lalibela’s sole (state-owned) petrol station runs out. Visitors can fly up from Addis on Ethiopian Airways every morning, but private airlines are pretty well kept out.

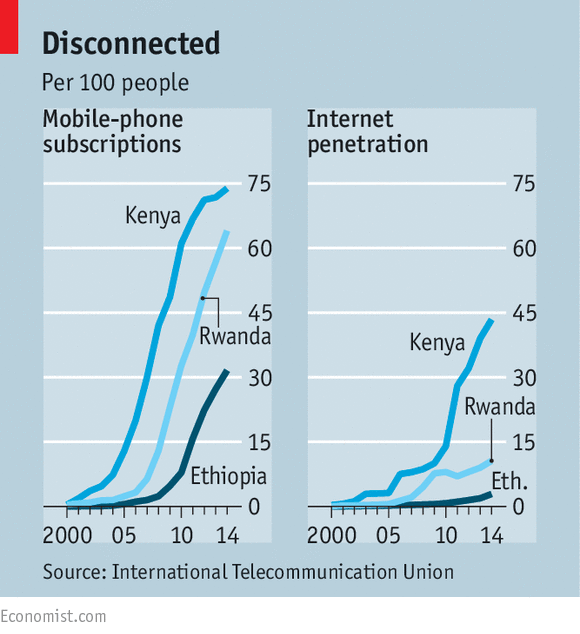

Many of these annoyances could be removed—if only the government were brave enough to set the economy free. “The service sector here is one of the most restrictive in the world,” says a frustrated foreign banker. The government’s refusal to liberalise mobile-telephone services and banks is patently self-harming. Ethiopians have one of the lowest rates of mobile-phone ownership in Africa (see chart); the World Bank reckons that fewer than 4% of households have a fixed-line telephone and barely 3% have access to broadband.

The official reason for keeping Ethio Telecom a monopoly is that the government can pour its claimed annual $820m profit straight into the country’s grand road-building programme. In fact, if the government opened the airwaves to competition, as Kenya’s has, it could probably sell franchises for at least $10 billion, and reap taxes and royalties as well; Safaricom in Kenya is the country’s biggest taxpayer.

Moreover, Kenya’s mobile-banking service has vastly improved the livelihood of its rural poor, whereas at least 80% of Ethiopians are reckoned to be unbanked. For entrepreneurs like Ms Aitchison and her partner, Habtamu Baye, local banks may suffice. But bigger outfits desperately need the chunkier loans that only foreign banks, still generally prevented from operating in the country, can provide. A recent survey of African banks listed 15 Kenyan ones in the top 200, measured by size of assets, whereas Ethiopia had only three.

Land reform is another big blockage, though farmers can now have their plots “certified” as a step towards greater security of tenure. Given Ethiopia’s not-so-distant feudal past and the dreadful abuses that immiserated millions of peasants in days of yore, especially in time of drought, the land issue is sensitive; the late Meles Zenawi, who for 21 years until his death in 2012 ran the country with an iron fist and a fervent desire to reduce poverty, was determined to prevent a rush of landless or destitute peasants into slums edging the big towns, as has happened in Kenya. But the increasing fragmentation of land amid the rocketing increase in population is plainly unsustainable, even though productivity has risen fast through government-provided inputs such as fertiliser and better seed. (Ethiopia is Africa’s second-most-populous country after Nigeria; by some estimates it has nearly 100m people.) Most women still have four or five children. The standard family plot has shrunk to less than a hectare.

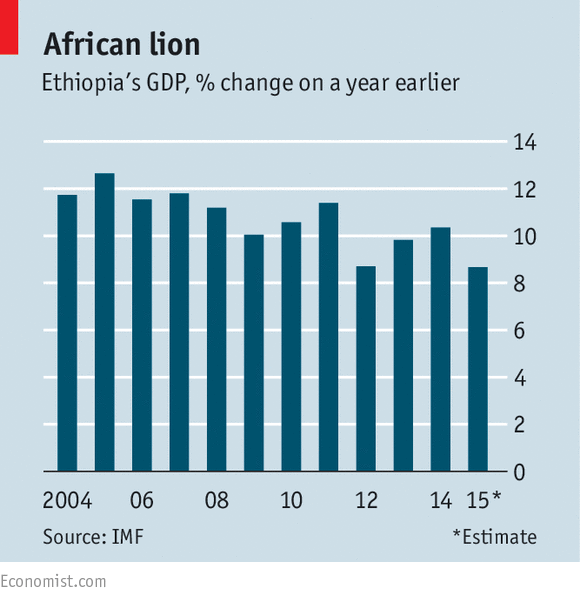

Yet, despite these self-imposed brakes, Ethiopia’s economic progress has been spectacular. Its growth rate, if the latest official figure of 11% is true, is the fastest in Africa; and even the lower figure of around 8%, which the IMF and many Western analysts prefer, is still very perky. Social and economic indices are reckoned to have improved faster than anywhere else in Africa, albeit from a low base. Extreme poverty, defined as a daily income of under $1.25, afflicted 56% of the population in 2000, according to the World Bank, but had fallen to 31% by 2011 and is thought to be dipping still. The average Ethiopian lifespan has risen in the same period by a year each year, and now stands at 64. Child and infant mortality have dived. Protection for the rural poor in time of drought, which presently afflicts swathes of the north and east, is more effective than before. The government has “the most impressive record in the world” in reducing poverty, says a British aid official. (Britain gives its fattest dollop of largesse to Ethiopia.)

Nonetheless, at least 25m Ethiopians are still deemed to be “extremely poor”. A waitress at Ben Abeba, a university graduate in biology, seems happy to get a monthly wage of $26. A labourer earns a lot less.

How they made a miracle

The core of the government’s economic policy is to improve agriculture, nurture industry and build lots of infrastructure. This includes a series of huge dams on the Blue Nile (which provides most of the water that flows into Egypt via Sudan) and on the Omo river, which flows south into Kenya’s Lake Turkana. The mass electrification that is expected to ensue should eventually help Ms Aitchison’s kitchen and communications in Lalibela.

Roads and railways are also being built apace. Driving east from the town on a dirt track to join a paved road 80km or so away, your correspondent saw not a single other vehicle in two hours. The government puts its hope in industrialisation and light manufacturing, spurred on by investment and also by mass education (more than 32 universities have been created since 2000). It promotes industrial parks, which are supposed to boost their share of GDP from 5% today to 20% within a decade—and create millions of jobs for a population whose median age is only 19.

Though the government invokes no precise model, it has various Asian ones in mind, most obviously China’s system of state capitalism under the strict control of a dominant political party. Meles rose to power at the head of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, a revolutionary regional party that originally drew its inspiration from Enver Hoxha’s Albanian brand of communism and which, after years of guerrilla warfare in the mountains, overthrew a vicious Soviet-backed Marxist regime, known as the Derg, in 1991.

Meles gradually began to open the country’s economy, but he also felt obliged to close down an experiment in multiparty democracy after an assorted opposition made big advances in a general election (which it claimed to have won) in 2005. The two main opposition parties, which both want to liberalise the economy and privatise the land, were eventually allowed to keep 161 seats in the 547-strong parliament. In the post-election fracas, about 200 people were killed and at least 20,000 are reckoned subsequently to have done stints in prison. In the next two rounds of elections, in 2010 and again in May 2015, the tally of opposition MPs, after a government campaign of outright repression, slumped to one and now none.

The opposition is crushed, fragmented and feeble. Prominent dissenters have fled or are behind bars. Human Rights Watch, a monitoring group based in New York, reckons there are “thousands” of political prisoners. Torture is routine. “Ethiopians are cowed,” says a longtime analyst. It was notable, at a recent Economist conference in Addis, that virtually no businessman, Ethiopian or foreign, had the nerve to disparage any of the government’s policies. In public Ethiopians tend dutifully to echo the government line; in private, though, they can be franker.

After Meles’s death, Hailemariam Desalegn emerged as prime minister. In September of 2015 he was confirmed as head of the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, itself a coalition whose key component is still Meles’s Tigrayan front. But Mr Hailemariam, a southern Pentecostalist from a small ethnic group outside Meles’s circle of revolutionaries from the north, has yet to achieve his predecessor’s authority.

Just take the plunge

He says he favours a loosening of economics and politics. But so far he has been tentative. “He’s a compromise guy encircled by old-guard Leninist ideologues, the Tigray boys,” says Beyene Petros, a veteran leader of the opposition. One of Mr Hailemariam’s close advisers, Arkebe Oqubay, a reformist who promotes industrial policy (especially the creation of industrial parks) and craves foreign investment, cagily suggests that banking will open up “in five years”. Yet the ruling front still reflects a deep wariness of foreigners who, in the words of a long-standing expatriate, remain widely suspected of plotting to “get rich at the expense of Ethiopians”.

Most independent observers feel that, overall, Ethiopia is on the rise, and may even emerge as an African powerhouse alongside South Africa and Nigeria—and ahead of Kenya, its regional rival. It is proud of having the African Union’s headquarters and of providing more UN peacekeepers than any other African country. It is a leading mediator in the region, especially in war-torn South Sudan, and has won plaudits from the West for its fierce stand against jihadism. It also caters for more refugees than any other African country—some 820,000 at last count.

On the home front, Ethiopia’s infrastructure plans have attracted the interest of potential investors from across the globe. Yet unless the government gets a move on frustration will grow, at home and abroad. If the ruling party had the courage to open up the economic and political system, the pace of Ethiopia’s progress towards prosperity and stability would quicken. Even lovely, remote Lalibela would gain.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.