Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s announcement on Jan. 1 of a memorandum of understanding with Somaliland marked a pivotal moment in his country’s long search for unrestricted access to the sea. The agreement would grant Ethiopia access to 20 kilometers (12 miles) of coastline, including the port of Berbera, through a 50-year lease. Freed from its most basic geographic constraint, Ethiopia could alleviate some of the internal pressure caused by its rapidly growing population and even develop a modest naval force in the Red Sea. If the deal further leads to Ethiopia’s diplomatic recognition of Somaliland, a breakaway province of Somalia, it could compel other countries to follow suit.

Somalia and others in the region have firmly rejected the agreement, which under most circumstances would be grounds for war. However, the timing appears favorable for Ethiopia and Somaliland. Around the Horn of Africa, Sudan’s civil war is devouring diplomatic attention and reducing others’ appetite for risk. Across the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, the focal point is Israel’s war against Hamas, including Israeli plans to retake control of the border between Gaza and Egypt. And in the waters between these areas, attacks by the Houthi rebels in Yemen continue to disrupt commercial shipping, resulting in a gradually escalating confrontation between the Iran-backed militia and U.S. and British forces. Assuming that these conflicts would limit Somalia’s ability to respond, Ethiopia chose this moment to make its move – and remake the region.

The Breakout and the Aftermath

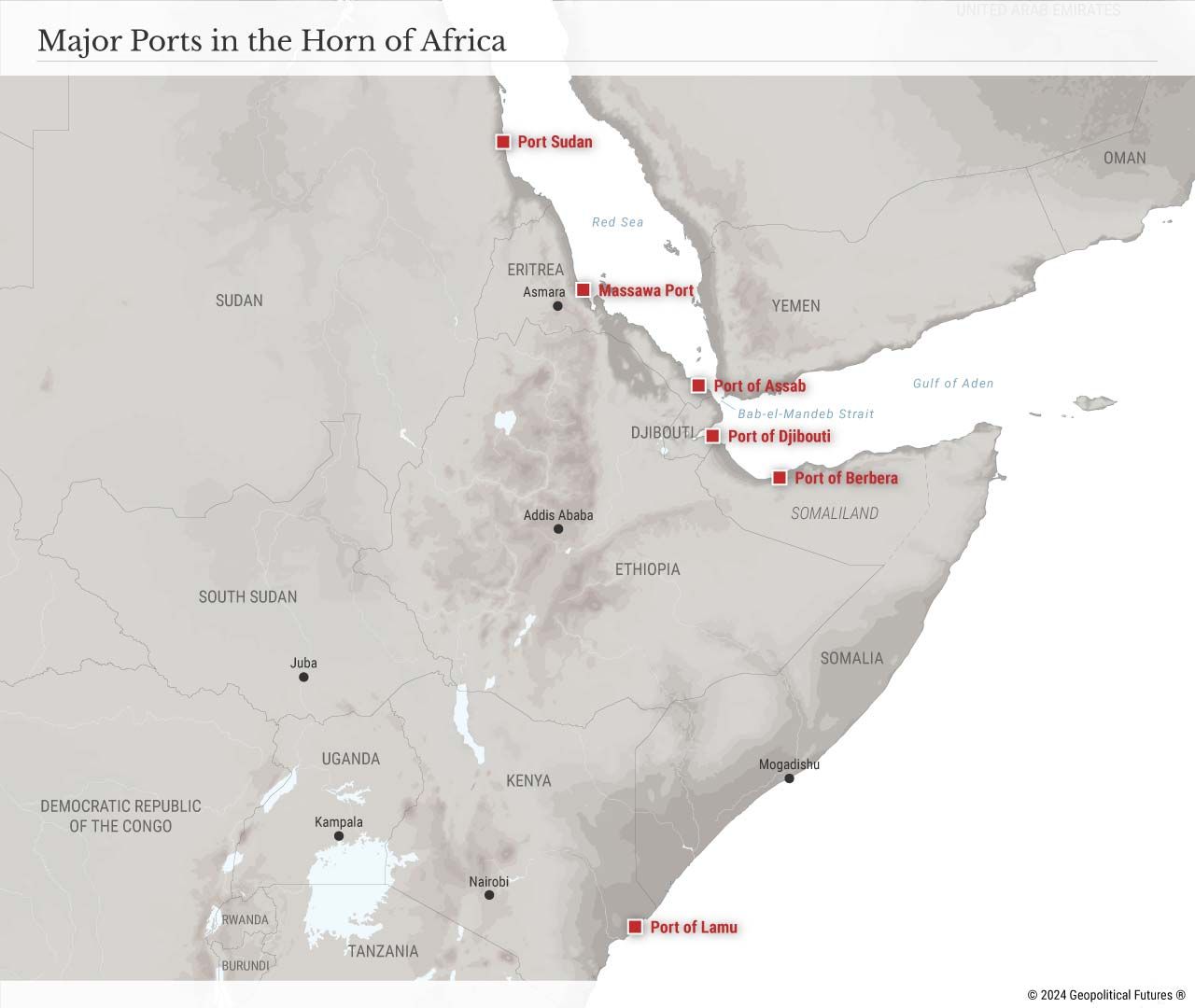

The Ethiopian prime minister outlined his determination to reach the seas last year, calling it “existential” for the country. Ethiopia has been landlocked since 1993, when after 30 years of conflict Eritrea broke away, taking its 1,000 kilometers of coastline with it. For the next five years, Addis Ababa was able to use Eritrea’s port of Assab, which handled two-thirds of Ethiopia’s trade, until the fighting resumed and the gateway was permanently shut.

Today, Ethiopia pays more than $1.5 billion annually to conduct trade through Djibouti’s ports. This has not prevented its economy from growing rapidly, but it has contributed to anxieties about debt. Moreover, as Ethiopia’s economy has grown, so have its interests and vulnerabilities. Population growth is becoming a concern as well. By 2030, Ethiopia’s population of more than 120 million is forecast to grow by about a quarter, to more than 150 million. Many Ethiopians already live in poverty, and about 20 percent (more than 20 million people) rely on food aid. To try to diversify its trade routes, Ethiopia reached out to Sudan and Kenya, but no solutions were found until the deal with Somaliland. Officials in Addis Ababa argued that the agreement would free up public funds and increase national security.

After the signing of the MoU was announced, Somalia renounced it immediately. For much of the latter half of the 20th century, Somaliland’s attempts to break away were a thorn in Somalia’s side. Finally, in 1991, the region declared its independence (not for the first time), but to date no U.N. member state has granted it recognition. If the deal with Ethiopia goes through, this could change.

For one thing, in signing the port access agreement, Ethiopia has in practice recognized Somaliland’s sovereignty. Formal recognition may follow, and then it would be only a matter of time before others did the same. In addition, Somaliland’s potential alliance with Ethiopia would make it a formidable contender to usurp Somalia’s role in the region. The authorities in Somaliland already wield greater control over their territory than Mogadishu does in the rest of Somalia. And while Somali security forces are tied down battling al-Shabab and pirates, Somaliland has no such problems and sits closer to the Bab el-Mandeb strait, the chokepoint separating the Red Sea from the Gulf of Aden. In neighboring Djibouti, the presence of the huge U.S. naval base at Camp Lemonnier as well as forces from France, Germany, Spain, Italy, the U.K., Japan, China and Saudi Arabia attest to the strategic importance of the strait.

An Opportune Moment

Addis Ababa’s interest in regaining sea access goes back decades, but two main factors contributed to its decision to move now and risk a conflict with Somalia. First, the balance of power favors Ethiopia. In contrast to Eritrea, which was Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s original target, Somalia’s armed forces are smaller and less well-trained. (War with Eritrea might also reignite the conflict in the Tigray region of Ethiopia.) Elsewhere, Egypt emphatically sided with Somalia against the agreement, even threatening an armed intervention. Cairo does not want Addis Ababa to develop a naval force that might one day threaten Egypt’s security in the Red Sea or further disrupt trade through the Suez Canal. But Egypt’s credibility was badly damaged after it failed to act on its repeated threats to stop Ethiopia from completing and filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which gave Ethiopia control over the Nile’s flow into Egypt.

The second factor favoring Ethiopia is the multitude of wars currently underway in the region. No country in the region exemplifies this better than Egypt. Hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees fleeing civil war have entered the country from the south, while the war in Gaza is destabilizing its northern border. For other opponents of the deal, it simply is not worth fighting over. Eritrea is threatened by Ethiopia and has recently strengthened ties with Russia and Iran for insurance, but the Ethiopia-Somaliland agreement would mitigate the threat by solving Ethiopia’s geographic dilemma. The Arab League has also strongly backed Somalia, but it lacks the desire or capacity to send troops on its own. Djibouti stands to lose significant revenues from port fees if the deal goes through, but it has tried to remain apolitical, not wishing to see a conflict on its border.

At the same time, several countries stand to benefit from the agreement, though they have been much more muted in their support. One of these countries is the United Arab Emirates, which has close relations with both Ethiopia and Somaliland (the port of Berbera has hosted a UAE military base since 2017) and is competing with other Middle Eastern powers to extend its influence deeper into Africa. Another is Israel, whose interest in the Horn of Africa has grown since Eritrea began to establish better ties with Israel’s arch nemesis, Iran. Finally, the U.S. could benefit if Ethiopia were to emerge as a more powerful security actor and develop a naval capability in the Red Sea. Unlike other governments, Washington issued an ambiguous statement on the MoU that could be read by both Somalia and Somaliland as support for their territorial integrity.

New Beginnings

What matters next is whether Ethiopia and Somaliland act on their agreement. This encompasses the development of the port and waterfront, enhancing infrastructure connections between Ethiopia and Berbera and the potential deployment of Ethiopian troops in Somaliland.

Ethiopia’s determination to secure independent sea access is driven by its imperative for trade expansion, economic growth and national security. Despite the vocal opposition from Somalia and Egypt, Ethiopia seems unwavering in its commitment to the agreement with Somaliland. Though rhetoric from Mogadishu points to a heightened risk of conflict, actual confrontation remains improbable unless Somalia garners substantial support from its Arab League allies. Ethiopia’s potential recognition of Somaliland could start a domino effect, and an internationally recognized Somaliland would not only serve as a strategic ally for Western countries, given its stability and democratic governance, but also further complicate strategic relations in the Horn of Africa.

The strategic timing of this agreement appears to favor Ethiopia and Somaliland, as regional and international distractions reduce the likelihood of significant intervention from other actors. Ethiopia’s pursuit of maritime access, a critical step in breaking free of its “geopolitical prison,” seems poised for success, simultaneously paving the way for Somaliland’s journey toward full statehood.

Ethiopia’s Timely Sea Access Deal With Somaliland

January 30th, 2024

January 30th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, commentary on Ethiopia’s sea access deal with Somaliland:

This entry was posted on Tuesday, January 30th, 2024 at 10:14 am and is filed under Ethiopia, Somalia, Somaliland. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.