August 4th, 2015

Courtesy of The Economist, an interesting article on the obstacles facing businesses when they assess new frontier markets:

IF THE lobbies of Tehran’s more expensive hotels are any guide, the rush is already on. Six months ago they sported only the odd Chinese businessman. Now they are alive with Westerners jostling for deals. Trade delegations have started to arrive. First off the mark after Iran struck a nuclear deal with world powers earlier this month was Germany’s vice-chancellor, Sigmar Gabriel, who took a group of executives to Iran’s capital on July 18th.

In Havana, too, hotels are bustling. Even before America and Cuba opened embassies in each other’s countries on July 20th, bookings were up. Ever since the two announced a rapprochement late last year, Cuban-born American lawyers have been arranging business trips to the Cuban capital for their best clients, with the added promise of fine rum, cigars and tropical nostalgia. American businesses are eager to catch up, having long watched Canadian, Spanish and other firms steal a march.

This unusual conjuncture of two long-isolated countries heading back into the commercial mainstream is good for consultants, too. At the start of the year ILIA Corporation, a Tehran advisory firm jointly run by a German and an Iranian, had no foreign companies on its books. By April it had three; it now claims 18. At American law firms, meanwhile, experts on other areas are being drafted into the Cuba teams to handle the workload. Pedro Freyre of Akerman, one of those firms, sums up the mood: “Oh my gosh. My phone has not stopped ringing. It’s been insane.”

All the activity notwithstanding, the initial rush to reconnoitre Cuba and Iran will slowly but surely give way to a more measured approach for most. It will be months, if not years, before the sanctions on both countries will be lifted. Even then foreign firms will face big obstacles to conducting business, let alone making profits.

The Cuban and Iranian economies are starkly different: one is a tiny island lying off the tip of Florida, the other a Middle Eastern power sitting on an ocean of oil. The type of sanctions on the two countries differ, too. Those against Cuba apply almost exclusively to Americans. In the case of Iran, they also bind non-American entities. European and Asian banks that do business with Iran without official approval, for instance, risk seeing their accounts shut down.

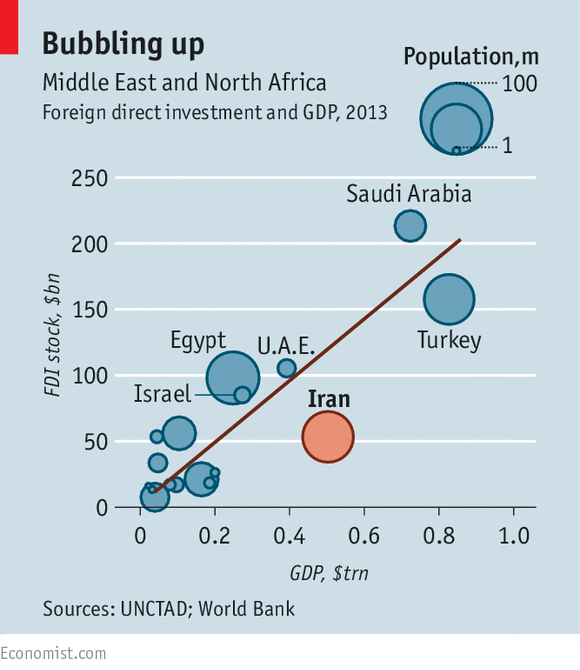

But Cuba and Iran do have one thing in common: they are developed enough that they could thrive once the restrictions are lifted. Iran in particular ought to be able to attract much more foreign direct investment, given its size (see chart). Many other countries targeted by sanctions are more chaotic and have less well-educated populations, and are thus “not poised for a growth spurt once sanctions come off”, says Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Some early moves in Cuba have been promising. Charter airlines have done a good trade ferrying the 12 categories of Americans (excluding tourists) now allowed to travel to the island. And tapping into Cuba’s booming private rental market, Airbnb executives say some 2,000 people have listed space in their homes via the online agency, charging up to ten times the average $25 monthly salary per rental.

As befits the larger economy, opportunities in Iran are grander. “Few countries have such immediate investment requirements,” says Rocky Ansari, a commercial lawyer and business analyst in Tehran, who estimates Iran’s pent-up need at over $1 trillion. In the next five years the country needs an estimated $230 billion-$260 billion of investment in oil and gas, according to analysts. Infrastructure badly needs an overhaul. Iran Air, starved of investment since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, wants to buy several hundred planes.

Some green shoots with foreign roots are already in place. Debenhams, a British chain of department stores, has several outlets across Iran, including one on a main thoroughfare in Tehran. Boeing is back bidding for business, and after an earlier round of sanctions relief in November 2013, is again selling spare parts. “Click here to apply for a franchise in Iran,” reads the website of McDonald’s, a fast-food chain.

In both countries, however, chickens are yet to hatch, let alone get turned into nuggets. Big food companies are hungry to enter Cuba, but the embargo prohibits them from using American banks to get letters of credit in order to make the deliveries. Even industries with permission to trade with Cuba, such as agriculture, medicine and telecoms, find obstacles in their way. The biggest is finance. Though the Obama administration removed Cuba from its “state-sponsor-of-terrorism” list in April, easing restrictions on banking, the response has been slow. On July 21st Stonegate Bank in Florida became the first American bank to set up a correspondent account in Cuba, allowing financial transactions between the two countries.

Similarly, even if the Iran nuclear deal passes Congress, the Islamic Republic still has to implement 11 related measures, and a plethora of sub-clauses. A dispute over any one of them could “set everything kicking off again,” fears a businessman travelling from London to Tehran. A 65-day “snapback” mechanism to reimpose sanctions if the deal is breached will discourage banks from again transacting with their Iranian counterparts. As long as they hold back, much of Iran’s $100 billion in oil revenues held abroad will remain there.

Jon Epstein, a lawyer at Holland & Knight in Washington, DC, says his advice to clients is not to try and be the first American firm into Cuba, but to give themselves a five-year horizon for entering the market. He believes that the experience there—more than half a year of ups and downs—has been a useful reality check that businesses are now applying to Iran. “At this stage we’re only talking of potential sanctions relief,” says Nigel Kushner, a British lawyer advising firms on Iran.

The biggest obstacle to post-sanctions growth may be the two countries’ own governments. Cuba’s embrace of private enterprise has been halting, to put it kindly. Authorities have been slow to vet foreign-funded projects in the Mariel special economic zone; only five have been approved in the past 18 months. Cuban bureaucrats are fanatically risk-averse and inscrutable. “It’s not knowing the ‘who’ to approach and the ‘how’ to go about it that’s the problem,” says Thomas Goodman of the Cohen Group, a consultancy.

In Iran Mohammad Javad Zarif, the foreign minister, presented the nuclear deal to parliament as a triumph. But behind his smiles a host of problems dog the economy. Iran ranks 130th on the World Bank’s table of easiest countries for business. Its absence from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, a World Bank-run commercial-arbitration service, give investors pause. Corruption is rife, and revisions to an old commercial law are bogged down in parliament.

For all his election promises, President Hassan Rohani has barely begun to tackle the vested interests that relished sanctions as a form of protectionism that kept competition out of the market. The Revolutionary Guards control huge swathes of the economy. “Ali Khamenei [the Supreme leader] sees globalisation as a national-security threat, and wants the Revolutionary Guard as the economy’s shock-absorber” against such forces, says Ali Alizadeh, a political analyst in London. Lifting sanctions will open the door to investors. But only if the rulers in Havana and Tehran want reform will economies be transformed.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.