The coming few years will be a litmus test for India’s ambition to become a manufacturing hub rivaling China. A big question mark is how quickly it can build out the infrastructure it needs to really seize the opportunity. There have been signs of progress recently, but New Delhi’s cramped fiscal space means it needs to do more to entice private-sector investors, too.

India is experiencing a manufacturing renaissance of sorts led by Apple and its Taiwanese suppliers—after decades of failed efforts. As recently as the fiscal year ended in March 2018, India was a importer of smartphones to the tune of more than $2 billion. Last fiscal year, India was a net exporter of $11 billion worth. About half of that was Apple products, according to investment bank Macquarie.

Apple is blazing a trail for other manufacturers that might still be on the fence about an India-centered “China+1” supply-chain strategy. India’s creaky infrastructure, exemplified by pothole-ridden roads and accident-prone trains, has kept many away. New Delhi’s aggressive government-funded infrastructure upgrade plans might allay some of these anxieties.

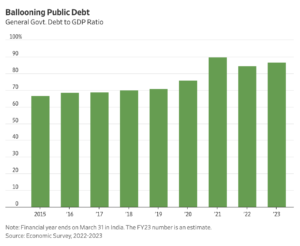

Eventually, however, the private sector will have to pitch in, because India’s government debt is quite high. The high-profile drama at infrastructure heavyweight Adani Group earlier in 2023 could also complicate matters—although the lack of fallout so far for bond investors helps.

India’s National Infrastructure Pipeline envisages 111 trillion rupees, equivalent to $1.33 trillion, of infrastructure capital expenditures from fiscal years 2020 to 2025. Energy, roads, urban infrastructure and railways account for the majority of the program. The pace of construction for national highways has increased sixfold compared with levels from 2002 to 2010, the average speed of freight trains has increased over 50% in the past two years, and wait time at ports has fallen by 80% since 2015, according to Macquarie. India’s road network has grown some 40% in length over the past decade to reach 6.3 million kilometers—the world’s third longest, according to consulting firm Gavekal.

India, with a history of poorly managing big infrastructure projects, has also taken several steps to mitigate the problem of delays and cost overruns by streamlining its administrative approach. Still, government data from October shows nearly half of 1,788 big-ticket infrastructure projects monitored by the central government were behind schedule and faced cost overruns of about 17%.

India’s focus on shoring up its shoddy infrastructure is critical to attracting dollars into the fledgling manufacturing sector, which accounted for just 13% of its gross domestic product last year, compared with 28% for China, according to the World Bank. Logistics costs were 18% to 20% of total production costs in India, versus 8% to 10% in China, according to Macquarie.

India is beginning to borrow from China’s infrastructure playbook, but still has a long way to go. According to Bernstein, China’s gross fixed capital formation peaked at 45% of GDP in 2009, up from 25% in 1990. Government funding was a major factor. India’s level is currently around 30% of GDP, according to Bernstein, up from the low 20s in the 2000s with private and household contributions dominating.

Moreover, while India might want to further increase public investment in infrastructure, it might be tough to match China’s level. India’s public debt load stands at about 85% of GDP—second only to Brazil among the emerging economies. The International Monetary Fund warned last week that India’s government debt could exceed 100% of GDP in the medium term.

That gives the government limited fiscal space to expand spending indefinitely. The hope is that more government infrastructure dollars will help anchor private-sector investment too by removing key logistical bottlenecks and sharing financial risks—especially now that foreign manufacturing investment is pouring in. Gavekal says that if the private sector can deliver, India can probably sustain total annual capital spending growth of up to 10%.

Catching up with China doesn’t necessarily mean copying its playbook entirely. To meet its manufacturing ambitions, India must find its own path to upgrading its rotting infrastructure.