August 19th, 2015

Courtesy of The Economist, a look at the rise of North Korea’s “monied” class:

PEALS of laughter rise from the front-row seats of the capital’s Pyongyang Circus. Army troops have been treated to its signature slapstick: a Korean peasant posing as a mannequin torments an American soldier (big-nosed, blond-wigged). Troops are the state’s ready labour, and the show is their reward after being ordered to do months of toil on the city’s newest construction sites.

Since Kim Jong Un came to power following the death of his father in December 2011, North Korea’s Young Leader has shown a passion for construction projects, with the emphasis on leisure—a pursuit he promised his subjects early on, along with prosperity. Mr Kim swiftly ordered the renovation of Pyongyang’s two main funfairs. A new water park, a 4D cinema and a dolphinarium have followed, along with riverside parks, residential skyscrapers and a new airport terminal, which opened last month. Now an underground shopping centre in the heart of the capital is being constructed to cater to a small class of newly monied Pyongyangites.

At its apex sit the donju, wealthy traders whose investments have been fuelling a retail and construction boom in Pyongyang and a few other cities. Informal trading has been a feature of North Korean life since markets arose as an unplanned response to widespread famine in the late 1990s and the collapse of the state’s public distribution system, through which nearly all goods were apportioned. Now some donju run businesses within North Korea’s state-owned enterprises, quasi-autonomous ventures that a bankrupt state tolerates in exchange for a chunk of the profits.

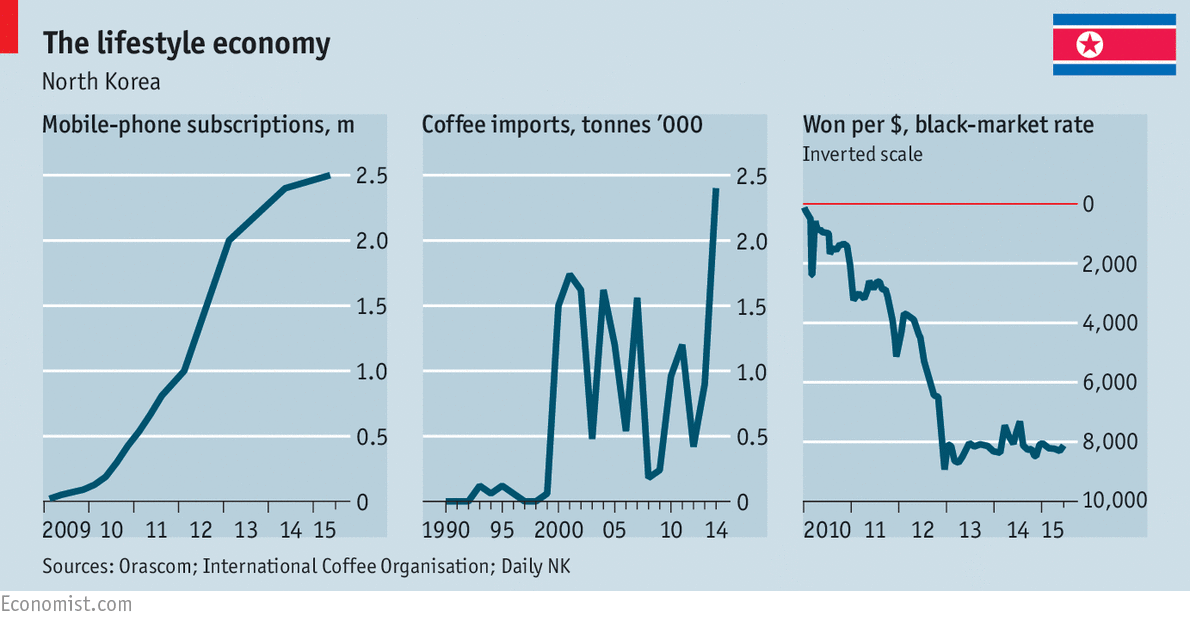

It is starting to change the face of the capital. Work on a cluster of new high-rise apartments was finished in around a year near Changjon Street, a quarter that local diplomats now refer to as Pyonghattan. Successful donju own some of the foreign cars on the city’s busier streets. Others ride in its expanding fleet of taxis. Most own smartphones, making calls and surfing a heavily monitored intranet through Koryolink, a joint venture between the state and Orascom Telecom, an Egyptian firm.

This growing segment of the population is already visible on Pyongyang’s streets as young women shrug off dowdy outfits for fitted jackets, bolder colours and sunglasses (long the mark of female villains in North Korean films). Coats with a discreet Burberry pattern on the lining are popular. One North Korean in her 30s was recently sporting a large diamanté Chanel brooch directly above her obligatory pin of the Kim rulers. A woman was even spotted carrying a tiny pet dog in her designer handbag—a sight common enough in Tokyo or Seoul but improbable in Pyongyang even five years ago. High heels have appeared, some in leopard print or silver.

The country’s dictator always weighs in sooner or later on matters of import, usually in pieces of set-theatre in which Mr Kim is seen to be delivering “on-the-spot guidance”. So it should have been no surprise that Mr Kim was recently giving guidance about high heels at a state-run shoe factory, and urging a cosmetics firm to compete with foreign luxury brands. (Besides, in the matter of fashion, Ri Sol Ju, Mr Kim’s young wife, is seen as something of a trendsetter.) It is even tantalisingly possible that state industry is responding to market trends. Kwangbok department store in west Pyongyang sells colourful waterproof jackets, pink popcorn and a copy of a South Korean chocolate biscuit stick, all made locally. One of 310 exhilarating slogans published by the regime this year enjoins: “Resolutely thwart the sanctions schemes of the imperialists by effecting a great upswing in light industry!”

Entrepreneurs are looking to set trends. At a three-day training workshop for businesswomen in Pyongyang run by Choson Exchange, a non-profit group based in Singapore, a government employee in her late 20s said she wanted to open the city’s first dessert shop, or a manicure salon. Through informal market research, she saw huge potential for both. Other female participants were running coffee shops, saunas and restaurants.

At the weekend donju families make their way to Sunrise Coffee, a lounge and pastry shop, for black-forest cake, ice cream or even an Old Fashioned. As at many other restaurants and shops now, customers can pay with a cash card, called a Narae card, that may only be loaded with foreign currency. It was introduced in late 2010 by North Korea’s foreign-trade bank—a neat way for the state to amass hard currency. An espresso is priced at 360 North Korean won, which really means it costs $3.30 at the official rate of 109 won to the dollar.

On paper, cocktails for four (4,000 won) are the equivalent of a civil servant’s monthly state wage. In practice, nearly all workers earn a second income in the unofficial economy. Some reports even suggest that the state has started to pay some workers at the real, black-market rate of around 8,000 won to the dollar. That slow, unheralded recognition of the market economy is evident at Kwangbok department store, a joint venture with a Chinese trading company. Unlike at Sunrise Coffee, all goods are marked and sold at prices close to the black-market rate.

During a Friday lunchtime the Kwangbok store is humming. Goods from North Korea, China, Vietnam and Singapore vie on the shelves. A bottle of Chivas Regal Scotch whisky sells for 272,000 won, about $34. L’Oréal Garnier shampoo is 40,000 won. A pack of Chinese-made sanitary towels is priced at 10,500 won. Tellingly customers must pay for all these in won—the government may have made that a proviso of the joint venture, deeply embarrassed that North Koreans buy and sell in dollars (though euros and Chinese yuan are now more popular). A booth near the checkout tills exchanges foreign banknotes for domestic currency, at around the black-market rate.

For all the change in Pyongyang, this kind of shopping remains within the reach only of a select few. Income inequality appears to be growing rapidly between those living in Pyonghattan and those in the city’s shabbiest districts, between those who own cars and those who cannot yet afford a smartphone. But the starkest contrasts are with the North Korea beyond the capital’s checkpoints. If the North Korean economy has grown—by about 1% a year since 2011, according to South Korea’s central bank—few outside Pyongyang and a handful of other cities would know it. Top-down experiments to allow farmers to sell more of their own crop for private profit have yet to take root. A severe drought this spring has squeezed already meagre electricity and food rations, and prompted the government to mobilise subjects to work extra hours on collective farms.

The sights on the country road to the town of Pyongsong, an hour’s drive north of the capital, tell of little change: a lorry powered by gas from burning wood chugging past men who are walking oxen through fields; women washing their clothes in a stream. To them and millions of others, Mr Kim’s trumpeted promises of a new era of prosperity and leisure must still sound hollow.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.