June 27th, 2017

Via The Diplomat, an interesting look at China’s potential to unite the Pamir know via its OBOR initiative:

Towering above the arid steppes of Central Asia is the rooftop of the world, the Pamir Knot, where Earth’s most striking mountain ranges – the Himalayas, Tian Shan, Karakorum, Kunlun, and Hindu Kush – converge, forming a bulging mass of piercing rock and glacial ice. The byproduct of a violent collision of the Eurasian and Indian tectonic plates, the region’s rugged passes and restless river gorges have guided the geopolitical forces of history, from the armies of Alexander to nomadic conquerors like Timur, to the obscure Russian and British explorers of the Great Game, the 19th century contest for Eurasian superiority. Rudyard Kipling once described this mountainous zone as “a world within a world.”

With the Belt and Road Initiative, and the addition of Pakistan and India to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China has formally embarked on the hazardous climb into this realm. Undoubtedly Beijing’s new engagement will change the calculus for the region’s players. In these Asian highlands, however, ambition is tempered by reality. The gnarled strands of these mountains lead to geopolitical pitfalls – from the Fergana Valley to the Wakhan Corridor to the Vale of Kashmir. Here, new silk roads may lead to old dead ends. Following the recent spate of summit diplomacy, can Beijing untie the Pamir Knot?

Summit Diplomacy

At the opening of the Belts and Road Forum on May 14, 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping celebrated the “spirit” of the Silk Road, the ancient trading system that spanned Eurasia’s vast steppes, mountains and deserts, connecting disparate civilizational centers from Asia to Europe. With the attendance of 29 heads of state and representatives from over 130 countries, the event was heralded as a demonstration of China’s global leadership, a savvy display of Beijing’s soft power, and a notable contrast to an increasingly inward-looking America under the leadership of President Donald J. Trump.

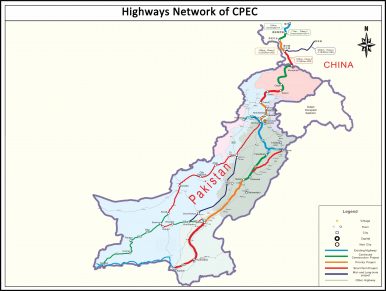

The forum’s joint communiqué called for promoting “practical cooperation” in developing interconnected multimodal corridors based on large-scale infrastructure projects, consistent with China’s “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) scheme. The Silk Road Economic Belt – the land corridor of the OBOR – traverses Central Asia, with a main spur, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), penetrating South Asia, from the Himalayas down to the Indian Ocean. As further explored below, a notable holdout to the OBOR is India, which has protested CPEC on sovereignty grounds. CPEC crosses territory that is administered by Islamabad, but claimed by Delhi as part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Given this heated dispute, the recent addition of India and Pakistan to the SCO is a fascinating development.

The SCO Summit, held in Kazakhstan on June 8-9, 2017, represented an important landmark in the organization’s development over the course of two decades. As I discussed on CGTN America, China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (the “Shanghai Five”) initially founded the SCO in 1996 in order to address border security following the Soviet Union’s collapse. With the addition of Uzbekistan in 2001 and now the South Asian powers of Pakistan and India, the SCO’s geographic scope and potential mandate have grown significantly. At the SCO Summit, members pledged to take on the traditional issues of terrorism and state instability, but also discussed matters like trade and climate change.

The Chinese-led SCO most obviously provides a security compliment to the economically oriented OBOR. Through this two-pronged engagement with Central Asia, Beijing seeks to stabilize its western periphery, where the restive Chinese province of Xinjiang, the homeland of the Turkic Uighurs, shares an extended border with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The ancient commercial pathways of the Silk Road also carry the modern transnational threats of ethnic conflict, terrorism and religious extremism. Perhaps nowhere is this dynamic more evident than along the passes linking Xingjian to the Fergana Valley.

Fergana Valley

The Fergana Valley is impressed like a thumbprint in the heart of Asia, cradled by the Tian Shan Mountains to the north and the Gissar-Alai range to the south. Due to its fertile ground, supported by the Syr Darya River, the Fergana Valley has long-been an important agricultural and political center in the region. Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, began his life trek to Agra from the valley’s slopes.

The current national boundaries of the Fergana Valley, drawn during the Soviet era, reflect Joseph Stalin’s vision of reinforcing ethnic divisions in order to preserve Moscow’s outside grip on power. The result is an odd patchwork of national boundaries, preserved under the doctrine of uti possidetis, which divides the valley among the post-Soviet states of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Traversing the valley’s length requires crossing several international boundaries, creating obstacles and tensions for the Fergana’s ethnically diverse and densely populated dwellers. Unsurprisingly, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, all SCO members, have not consistently shared a common view on security matters ranging from border demarcation to transit routes to water resource allocation.

For instance, Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, located on the Uzbek border on the eastern edge of the Fergana Valley, has been the setting for recurring ethnic violence. In June 2010, riots in Osh pitted the Kyrgyz majority against the minority Uzbek population, resulting in hundreds of deaths and a large-scale refugee crisis that displaced approximately 400,000 people. After a limited incursion across the Kyrgyz border, Uzbekistan’s forces withdrew to field fleeing refugees. The inter-communal strife followed the toppling of Kurmanbek Bakiyev’s regime in Bishkek, almost exactly five years after the so-called “Tulip Revolution” that felled Askar Akayev. According to an independent inquiry, the 2010 Osh riots demonstrate how the rise of ethno-nationalism has challenged state capacity and the integrity of multiethnic states in Central Asia.

Two decades earlier, amid the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1990, a similar clash in Osh had forced Moscow to deploy Soviet paratroopers in order to quell the unrest. During the 2010 iteration, the interim government in Bishkek requested Russian assistance via Kyrgyzstan’s membership in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Moscow-led military alliance (members include Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan). Despite the appeal from Kyrgyzstan, CSTO declined to intervene, raising questions as to CSTO’s capacity and role as a regional security organization. Indeed, Russian-led organizations involving Central Asian states – like CSTO and the Eurasian Economic Union, a regional trading bloc – may give way to Chinese-led platforms like SCO and the OBOR, particularly if these instruments prove more effective in addressing core security and economic issues.

One of the primary purposes of the SCO is to combat terrorism. The SCO’s permanent counter-terrorism arm, the Regional Anti-terrorism Structure (known by its unfortunate acronym, RATS) is based in Uzbekistan, which is notably not a member of CSTO or the Eurasian Economic Union. A significant threat to the Uzbek capital of Tashkent has been the Islamic of Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), one of the region’s leading terrorist organizations. Although weakened by the United States’ 2001 military intervention in Afghanistan, the IMU has regrouped and embraced the Islamic State. Among the safe havens of the IMU and other extremists is a porous stretch of Afghani borderland, the Wakhan Corridor.

Wakhan Corridor

Part of the northern Afghan province of Badakhshan, the Wakhan Corridor cuts a curious shape on the political map – a narrow panhandle separating Tajikistan and Pakistan, a pointing Afghan finger aimed at China. Marco Polo traversed the valley en route to Kashgar, the ancient Silk Road station in western China. The Wakhan’s dimensions, less than 20 kilometers at its narrowest point, are the result of a joint effort of Tsarist Russia and Victorian Britain to delimitate Afghanistan’s northern border. During the Great Game, the Wakhan Corridor ensured that the two European empires would not meet in Central Asia, underscoring Afghanistan’s historical and ongoing role of buffer zone in international affairs.

Today, Afghanistan is a potential lynchpin for linking energy producers in Central Asia with energy consumers like China and India. China has reportedly been constructing border access routes and supply depots in the Wakhan Corridor in order to facilitate China’s access to Afghanistan’s natural resources. The SCO expansion to include India and Pakistan increases the probability for long-dormant energy projects like the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline. The economic potential of Central Asia, however, is dependent on the stability of Afghanistan – a geopolitical conundrum that creates serious challenges for regional cooperation.

Among the various difficulties in Afghanistan is the shifting balance of power between the internationally recognized government in Kabul and insurgent groups, namely the Taliban. In a recent interview, Zalmay Khalilzad, former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, highlighted how the Taliban’s revival is changing the geopolitical calculus in the region. For example, China has supported Pakistan, the Taliban’s chief sponsor, in Russian-sponsored efforts to achieve a negotiated settlement in Afghanistan. Concurrently, in March 2017, Chinese troops were reported to be participating in joint Chinese-Afghan security patrols in the eastern “Little Pamir” region of the Wakhan Corridor, ostensibly to fortify Kabul against destabilizing forces like the Taliban. Indeed, in the 1990s, the Taliban’s rise posed a common threat and organizing principles for China, Russia and other SCO members. Now, the tables have turned, as Russia is providing weapons to the Taliban and challenging the authority of Kabul and NATO interests in Afghanistan, according to Senate testimony from General John Nicholson, commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

The contest in the Hindu Kush also extends to South Asia, where achieving Indo-Pakistani consensus in Kabul is a condition precedent for securing Afghanistan. Yet, competition in Afghanistan has been the primary theme for India and Pakistan. Since 2001, Delhi has deepened ties with Kabul, partly in response to destabilization efforts by Islamabad. In response, Pakistan has sought to undermine India’s increasing presence in Afghanistan. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency has been linked to a series of deadly terrorist attacks (e.g. August 2008, May 2014, January 2017) on India’s Afghan embassy and consulates. The Indo-Pakistani dispute has extended to multilateral discussions in which India has pushed back on efforts by Russia, China, and Pakistan to involve the Taliban in reconciliation efforts.

According to a recent Congressional report, China is assisting Pakistan to avoid the latter’s “encirclement” by India. With China defending its “all weather” ally Pakistan, India may look to the United States for assistance in shaping events in Afghanistan. Thus far, the Trump administration has failed to articulate an Afghanistan strategy and apparently has settled on a stopgap measure in the interim: a modest supplement to the approximately 8,400 American troops in Afghanistan. A recent op-ed from Shakti Sinha, Director of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, captured the concern in Delhi: the Trump administration’s disinterest and Beijing’s ascent will help Islamabad gain strategic ground in Afghanistan. Pakistan’s desire for “strategic depth” in Afghanistan is informed by one of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, Kashmir.

Vale of Kashmir

On October 8, 2005, a magnitude 7.6 earthquake rocked Kashmir, resulting in nearly 75,000 deaths, injuring more than 100,000 people, and causing extensive damage. Although the epicenter was on the border between the Pakistani- and Indian-administered portions of Kashmir, the quake and its aftershocks were felt across the region from Central Asia to China. The tremors of Kashmir also created volatility in the region’s already precarious security structure. This is due to the overlapping territorial claims of India, Pakistan, and China.

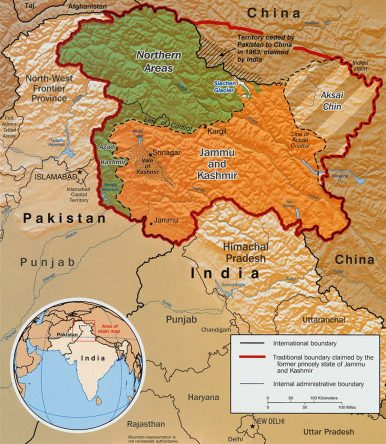

According to one tally, in 1947, at the time of independence for India and Pakistan, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir had an area of 222,236 sq. km. Currently, Pakistan occupies about 78,114 sq. km and China about 42,685 sq. km (Aksai Chin), including 5,180 sq. km controversially ceded by Pakistan to China (Shaksam Valley) in 1964. In turn, India only controls about half – 101,437 sq. km – of its claimed territory in Kashmir. This balkanization of Kashmir is the result of several major and minor armed conflicts. India and Pakistan have engaged in four wars (1947-48, 1965, 1971, and 1999) and repeated lesser clashes. In 1962, India suffered a humbling military defeat following a Chinese invasion of the Ladakh region of Kashmir and India’s eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh. The two countries nearly came to war in 1986-1987 and have engaged in numerous smaller border confrontations. For example, in September 2014, concurrent to President Xi’s first trip to India following the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Chinese military engaged in an extended incursion into Indian-claimed territory in Kashmir, as Indian forces scrambled to respond.

Disputed Area of Kashmir Map

This history of violence in Kashmir informs India’s protests regarding CPEC and boycott of the Belt and Road Forum. CPEC is a $46 billion infrastructure investment plan to develop Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, energy projects and approximately 2,000 miles of oil and gas pipelines, road and railway infrastructure. The Chinese-backed mega project is designed to mitigate Beijing’s “Malacca Dilemma” by creating an alternative trade route stretching from Xinjiang to the Arabian Sea and the Middle East’s energy supplies. The planned corridor enters at the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Kashmir, which is controlled by Pakistan, but claimed by India. India’s foreign secretary summarized Delhi’s position: “Fact is CPEC is part of this particular initiative [OBOR] and CPEC violates India’s sovereignty because it runs through PoK [Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir].” By creating new facts on the ground, like in the South China Sea, China could materially alter the status quo in a heated territorial dispute, in this instance, by potentially creating a fait accompli for Pakistan.

CPEC Highways Network

With Kashmir, the cold transactional calculus of Chinese economic development (creating “win-win” scenarios) must account for the fiery factors of sovereignty and nationalism. Much as the “century of humiliation” is central to the narrative of modern China, Kashmir is integral to the birth-story of Pakistan and India. In 1947, under the watch of the last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, Britain hastily exited the subcontinent, creating a void for the immediate assertion of two competing visions of the nation state: (1) the pluralistic secular democracy of India, as projected by Jawaharlal Nehru; and (2) the distinct Muslim homeland of Pakistan, as championed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In Jammu and Kashmir – a state where a Hindu maharaja ruled over a Muslim majority – India and Pakistan found a cause and defect in their respective national narratives. Even as the factual origin of Kashmir’s dismemberment is hotly debated, the dispute has resulted in a clear record of contrasting (but not mutually-exclusive) demands: from India, an end to Pakistani-supported terrorism and insurgency; and from Pakistan, a plebiscite to determine the future of Kashmir’s governance.

Needless to say, international and third-party intervention in Kashmir have been a point for further contention. With respect to regional cooperation, the Kashmir effect has hindered institutional approaches like the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). For example, following the September 2016 terrorist attacks in Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir, allegedly sponsored by Pakistan, India led an effective campaign to boycott the planned SAARC summit in Islamabad. There is concern that the Indo-Pakistani dispute could spill over into the SCO. More recently, following the SCO Summit, India reacted harshly to suggestions that Russia mediate the Kashmir dispute.

As India’s strategic might and political confidence increase, Pakistan may seek assistance in Kashmir from patrons like Russia or China. Certainly, China’s new entanglement through CPEC adds another layer of intrigue. Looming above all of Kashmir’s conflicts is the threat of nuclear war. Such considerations came to mind this week as Modi met with U.S. President Donald Trump in Washington.

Suspended Disbelief

In light of ongoing geopolitical tensions in the region, recent summit diplomacy in Central Asia suggests a willing “suspension of disbelief.” Pursuant to this artistic device, Aristotle explained that an audience is made to temporarily accept, as believable, events that would ordinarily be interpreted as unbelievable. How else to explain, for example, discussions on joint Indo-Pakistani counterterrorism exercises under SCO auspices? Nevertheless, it is a credit to Beijing’s ambition that players involved in struggles in the Fergana Valley, the Wakhan Corridor and Kashmir would engage in the appearance of collective security, if only as momentary fiction.

When we return to the craggily spines, from the Tian Shan to the Himalayas, the rising fissures of this tectonic borderland, we find a reality of war and a contest of wills. The geopolitics are as treacherous as the geography, and declarations of cooperation may only paper over entrenched fault lines. If the past is prologue, belts and roads may not be able to bridge the yawning rifts that divide the region. Yet, in pursuit of Pamir heights, Beijing appears determined to keep its eye on the future.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.