December 24th, 2023

Via The Economist, a report on the planet’s biggest conservation project in South Sudan:

As the helicopters whizz above the savannah eagles, storks and vultures swoop away from the scything blades. Voices on the intercom joke about the best height to avoid machine-gun bullets. Through the open doors the emerald hue of the plains seeps towards the horizon. In the grass there is life in abundance: lions, cheetahs, giraffes, baboons and, most of all, white-eared kob, the dainty antelope whose annual treks may be the biggest land migration of any mammal on the planet. To try to find out, a vet dangling from a chopper fires a tranquilliser dart at a kob’s rump, then leaps out to attach a collar. The scene is part “Apocalypse Now”, part “The Lion King”.

This is one of Earth’s largest intact ecosystems, in an area more than twice the size of Portugal. Yet no tourists come here, for it is in South Sudan, the world’s newest country—and one of its most dangerous.

South Sudan had a painful birth. It broke away from Sudan in 2011, and quickly plunged into a civil war that cost perhaps 400,000 lives (out of a population of 11m). That conflagration ended in 2018 but local conflicts smoulder. Since April a new civil war in Sudan, to the north, has driven refugees south, piling on misery. South Sudan is the world’s least developed country, says the United Nations. Life expectancy is 55, about the same as it was in America a century ago.

“There are a lot of negative perceptions,” concedes Rizik Zakaria Hassan, the minister for conservation and tourism. “That killing is rampant, that everyone is holding a gun.” Such pessimism is overblown, he argues; conflict remains “just in a few pockets”. Today South Sudan has a new story to tell.

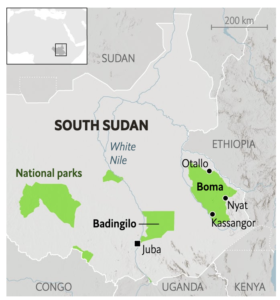

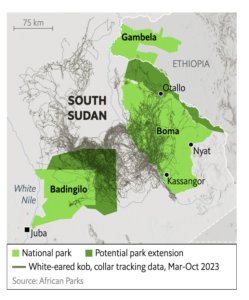

A year ago African Parks, an ngo, began a stunningly ambitious project. Under an initial ten-year deal with the government it will try to protect an area of 200,000km2, stretching from the White Nile in the west into Ethiopia in the east. To succeed, it must also bring benefits to the people who live there.

That will be hard, given South Sudan’s history. The area now within its borders was plundered by the Ottomans, neglected by the British and subjugated by Sudan, whose Muslim, Arabic-speaking rulers oppressed and enslaved black African southerners. In 2011 99% of South Sudanese voted for independence—a share beyond the wildest dreams of, say, Scottish nationalists.

But what did independence mean to people? There was little sense of a national identity—the country’s 60-odd tribes were paramount. Nor was there much of a state. Many South Sudanese still rely on aid for food, health care and education. When the pope visited Juba, the capital, in February the government tarred a few roads—but only along his route. Drivers now ask customers if they want to take the “Pope road”.

Oil, which supplies more than 90% of state revenues, has fuelled vast corruption. Politics is a violent marketplace, with groups using force or the threat of it to grab a larger share of the petrodollars. President Salva Kiir’s government endlessly tries to fight or pay off factions. The country has five vice-presidents and, by one count, more generals than America.

“After the wars broke out everything collapsed, including the wildlife,” says Khamis Adieng Ding, the director-general of the wildlife service. “When people fight they need something to eat.” Yet many areas were relatively unscathed. These include Badingilo and Boma, two national parks that are part of African Parks’s mandate. War is not always as bad for animals as it is for humans. It has curbed development, which means no roads for commercial poachers or loggers.

In Boma, earlier in 2022, African Parks was finding out which species were left—and in what numbers. Every morning Richard Harvey, the vet, would fire the darts from a helicopter, and hurtle out into the bush to collar animals. He chased an obstreperous eland for half a mile, dodging its horns like a khaki-clad matador. “If the lion comes at us, run to the chopper,” he advised, before jabbing a sedated male.

African Parks is astonished by what it has seen. Gobsmacking numbers of big cats; millions of antelope. A survey to be published in 2024 is expected to confirm that the kob migration is the world’s largest by land mammals, greater even than the famous trek of wildebeest over the Serengeti. Vast raptors, lacking exposure to man-made poisons, have survived in enormous numbers. What look like snow-capped hills in Boma are actually cliffs covered in vulture droppings. And whisper it: some conservationists suspect that northern white rhinoceroses, assumed to be functionally extinct, are chomping away in the bush.

“This place is very, very special,” says David Simpson of African Parks. “This is what the world used to be like; it is the only place that has these numbers of wildlife.” He adds: “We have a huge, huge responsibility…to save this place.”

Eyes on the prize

Doing so will be the ultimate test of African Parks’s model. Since it was founded in 2000, several governments have outsourced the running of their parks to the NGO. It raises capital from donors such as the EU and philanthropists like the Walton family. The group trains rangers, sharpens management and looks for ways to generate income, such as agriculture and tourism. After five years running a park it reduces poaching by 70% on average and increases wildlife numbers by 50%, it claims. It does this in places as poor and fragile as Chad, where it revived elephant numbers and built a luxury lodge. Mr Risik believes that rich tourists will one day flock to South Sudan, too.

That remains a way off. First, African Parks must win over hundreds of thousands of people who depend on the animals for their food and livelihoods. Locals have a profound sense of ownership over the land, even if they have never heard of a title deed. And they are sceptical of do-gooders and the state.

Your correspondent flew from Nyat and, after a comfortable night in a mud hut, met the king of the Anuyaks, a local tribe, in his kraal in Otallo, a village in Boma. Akwai Agada Akwai Cham Gilo sat atop skins of big cats and kob. Dressed in a leopard-skin shawl, he caressed a rusty shotgun, smiling as he explained how it was captured a century ago from the British.

Mr Akwai is surely the only former employee of Fine Impressions, a Minnesota-based envelope manufacturer, to reign over a South Sudanese tribe. He was a refugee in America, but after the then king, his half-brother, died in 2011, he picked up the crown.

His time outside South Sudan has given him perspective. He cites three main challenges. The first is education. There are no paid teachers at the primary school, where scores of pupils cram into classrooms hoping that volunteers from the village will turn up. The second is health care. The clinic in Otallo offers little save for nutritional sachets. The third is a lack of clean water. There is a pump in the village but demand is such that people camp out in the queue overnight.

Later that day Meet Ojwok Lero, a local leader, gives a tour of the village, gingerly stepping past huts seemingly floating on mud caused by heavy rains, through plumes of smoke rising from fish charred by burning dung. “The problem is we’re not connected,” he says. There is no phone signal, no internet, no paved roads, no grid. “This is the 21st century but it might as well be the 18th,” he adds, pointing at children heaving hoes.

Hunger for development poses a challenge for African Parks. It is neither an aid agency nor the UN; its mandate is to protect the parks. Infrastructure would bring modernity closer to indigence, but also to wilderness. A road north from Juba has encouraged deforestation as trees are felled to make charcoal for cooking. Plastics have polluted the Nile.

Another challenge is the rivalries among the tribes. Competition for resources and, in some cases, decades of intercommunal violence, have entrenched divisions. Near the clinic in Otallo Dimuy Owiti tells how two years ago she was walking home when three Murle, members of a neighbouring tribe, ripped her three-year-old daughter from the shawl in which she was cradled. “This is the culture of the Murle,” she says. “If you don’t kidnap a child, you’re not a true Murle.”

In private Murle admit that their tribe snatches children, but point out that their own children are snatched, too, and that kids can be exchanged for cattle, with a young girl fetching 20 cows. Violence is part of life’s backdrop. In 2023 Anuyak launched an attack in Nyat, ostensibly in reprisal for child kidnapping.

African Parks hopes that if it helps locals set up businesses, they will have less cause to poach or to steal each other’s cattle and children. Encouraging day-to-day contact—having Murle and Anuyak work together as rangers or spotters—may help break down suspicions and ease animosity.

However, the idea that a Western ngo can bring order and prosperity to poor parts of Africa—while stewarding millions of acres of land—has raised inevitable criticisms. Environmental activists and left-wing academics liken the notion to “green” colonialism.

Conservation in Africa does have a dark side. Indigenous people have sometimes been evicted to make way for foreigners who want private reserves. In 2022 Maasai in Tanzania lost a court battle against their eviction by the government, which reportedly wants to allow a firm backed by Emirati royals to open a luxury hunting lodge. Some conservation charities seem to care more about elephants and pangolins than about the Africans who live among them.

Yet not every conservationist is the same. African Parks is in some ways more like a substitute for the state than an animal-saving charity. “Logically we might not want any more development,” notes Mr Simpson. “But that is neither feasible nor moral.” He adds: “In the traditional idea of conservation it is either people or wildlife…but the people depend on the wildlife. It’s about the interface between them.”

African Parks seems to have made a good start. In Kassangoro, another village in Boma, Natabo Abraham, a leader of the Jiye group, says that no organisation that has worked in his area is as inclusive. Some aid workers may fly in and out to open projects that run out of funding within a year, but villagers in Otallo say African Parks is not like that. Its staff are happy to rough it, and often stay overnight.

South Sudanese yearn for a success story. They want their country to be known for something other than killing. For King Akwai it is obvious that protecting animals can also help his people. Asked about the white-eared kob, his eyes light up. “My favourite animal: we depend on them, we love them. Our children are born on their skins.” Unlike oil, which has enabled graft and misrule, “The kob is a renewable resource,” he adds. “We need the animal for future generations. The kob was created by God for us.”

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.