Peruvian President Dina Boluarte will pay a weeklong visit to China at the end of June – the first head of state to do so in nearly a decade. While there, she will meet with the CEOs of Huawei and BYD and with principals from Jizhao Mining, China Railway Construction and Cosco Shipping. Her itinerary has not gone unnoticed by the United States. Peru is a U.S. ally. Its coziness with China could call that into question.

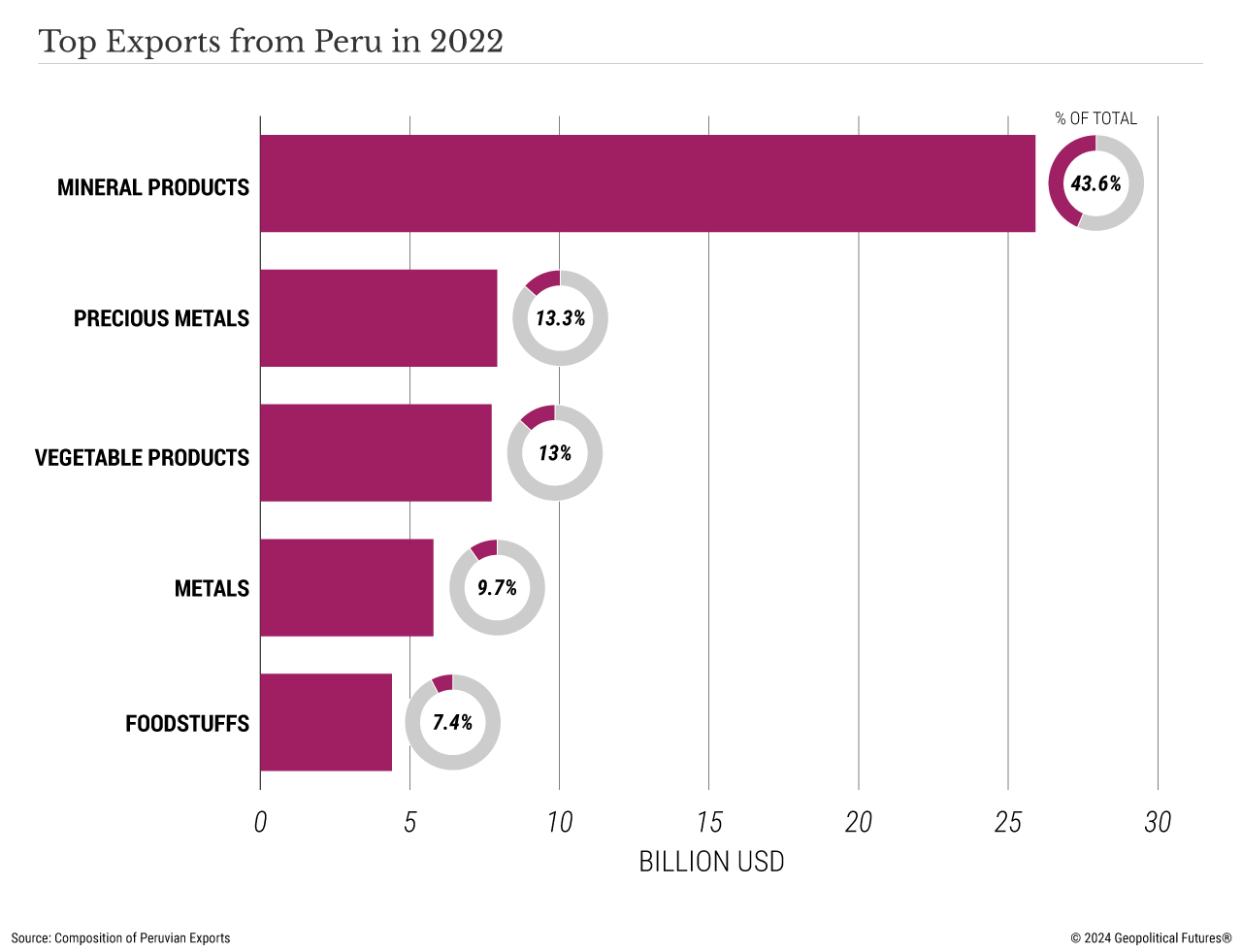

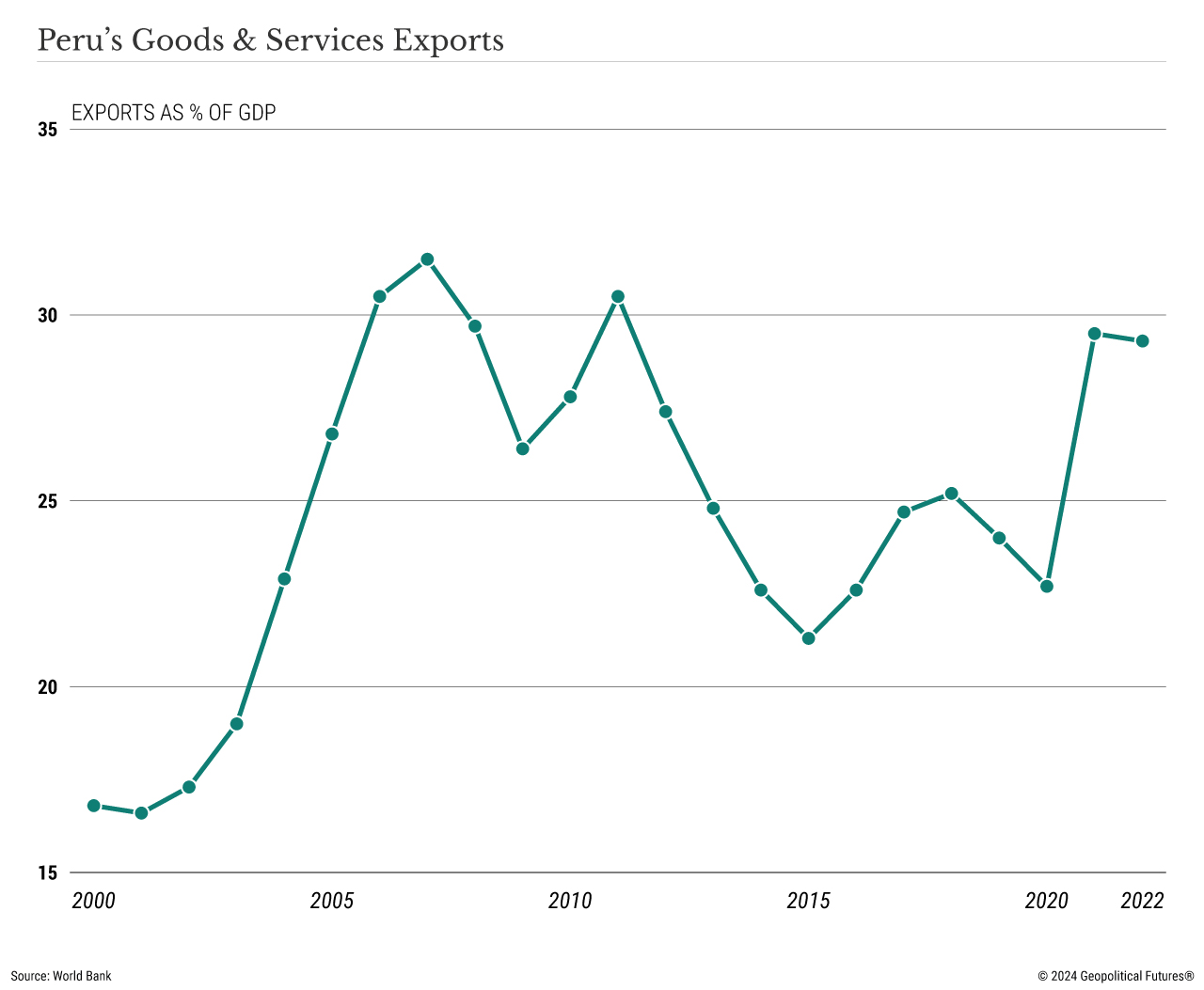

To be clear, Peru is courting China not because it wants to but because circumstances demand it. Last year, the economy contracted 0.6 percent after growing only 2.7 percent in 2022. The central bank remains concerned about upward inflationary pressure. Social unrest hit Peru’s mining sector hard in 2022, creating multiple production suspensions and $1.3 billion in loss and infrastructure damage, according to government estimates. Unsurprisingly, mining investments fell by 18 percent in 2023 as companies grew concerned about political instability and associated security costs. This is a major problem for a country in which mining accounts for nearly two-thirds of all exports and 10 percent of government revenue. Worse, it could prevent Peru from cashing in on the rising global demand for strategic metals the country is flush with – including copper, silver, lead, zinc and molybdenum, to name a few.

There are limits to what the government can do to solve the problem. Since 2016, Lima has been gripped by a political crisis that has seen seven presidents rise and fall from office. Boluarte herself has an approval rating of just 5 percent. Without the ability to enact the kind of sweeping reforms needed to fix structural economic problems, the government has instead tried to goose production from its only reliable engine of growth: extractive industries. Lima introduced several measures this year meant to manage and regulate mining exploration and operational activities with the express purpose of allaying investor concerns. It also spearheaded complementary efforts focusing on community dialogue, territorial planning and policy reform to minimize social unrest.

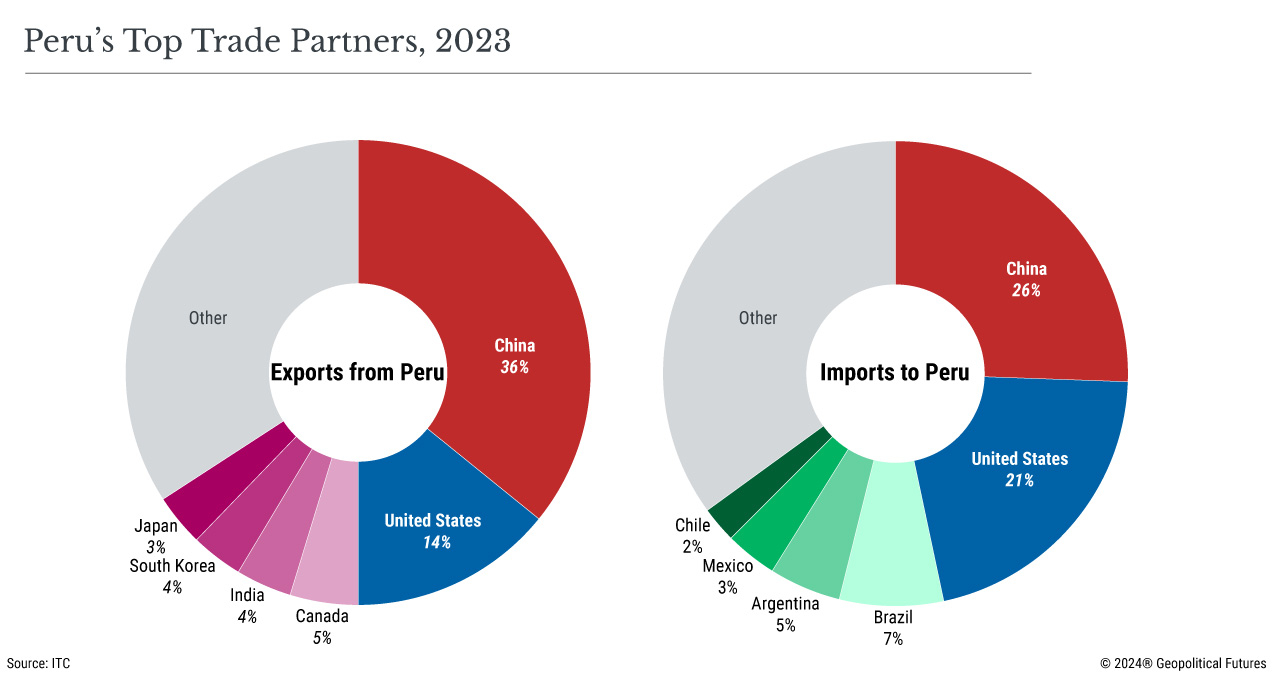

Under these circumstances, Peru’s relationship with China is almost existential. China has been Peru’s top trade partner for the past decade. It is among the largest investors in Peru and the largest investor in mining. The two signed a free trade agreement in 2009 to sync up with China’s economic boom and explosion in demand for natural resources. From 2012 to 2022, bilateral trade doubled, reaching $33 billion. And though its economy has slumped over the past few years, China is still a formidable presence in Peru and its mining sector.

The relationship has advantages for China. Beijing still relies heavily on metals imports to keep its domestic industry active. With its gigantic population, it must consistently work to ensure food security, and Peru is essential in that regard. Strategically, Peru has become only more valuable as China’s usual partners in Latin America grow less reliable. Venezuela, for example, is collapsing economically, while Argentina has adopted a more pronounced pro-U.S. posture of late. For Beijing, challenging the notion that Peru is an unwavering U.S. ally is an added bonus.

Though their short-term interests align, a long-term partnership seems unlikely. Some of the obstacles are practical. With regard to labor, for example, Peru prefers to employ local populations and coordinate activity within their communities. China doesn’t. Others are more fundamental. Peru’s economic ambitions are based largely on free market ideals instilled and accepted by U.S.-educated Peruvians. The country values transparency in the private sector more than China does. Moreover, Lima eventually wants to wean itself off its dependence on natural resources and develop more value-added goods. It aspires to become a regional digital tech hub and to make electric vehicles. While there is space for complementarity, China is much more interested in buying Peruvian minerals than it is in Peru’s long-term business plans.

The U.S. sees Peru and China’s relationship as dangerous because of the security risks it poses. For several decades, Peru has been one of the few stable, neoliberal countries closely aligned with the U.S. in Latin America. Put simply, Washington wants to keep Beijing at a distance, so the budding relationship, driven though it may be by economic necessity, goes against this interest.

The biggest concern for now is the Chancay Port project, which is 70 percent completed and slated for inauguration in November. The full project requires $3.6 billion of investment, which comes largely from China and Cosco. The initial deal granted Cosco exclusivity for port operations. There are concerns that the port could be used for dumping, that it could pull trade away from other nearby ports, or worse, that it could be used for military purposes. Article 7 of China’s 2017 intelligence law requires companies to support intelligence work, and Washington is uncomfortable with such a project so close to its shores.

To be sure, Peru has not forsaken the U.S. In fact, it has expressly said its ties to China won’t come at Washington’s expense. To that end, Peru’s National Port Authority tried but failed in March to remove the exclusivity clause for Cosco to be the sole operator of Chancay on the grounds that it jeopardized the legal stability of investments and violated Peru’s competition laws. Moreover, Lima recently suggested that U.S. companies could take the lead in the smaller but comparable Corio Port project, which could serve as an American alternative to Chancay. Meanwhile, Peru continues to work with the U.S. to formalize small-scale mining and fight the associated illegal operations that cost the government as much as $4 billion per year.

Washington has no plans to walk away from Peru anytime soon; it needs minerals and metals as much as the next country. And the U.S. has proved capable of taking pragmatic approaches to countries that need to balance their own economic interests with its security interests. (For example, it refrained from penalizing India when it continued to buy sanctioned Russian oil.) The future of its relationship with Peru is in its own hands. Peru will follow the money, and for now, China is uniquely positioned to deliver. But Lima has made clear it is more than happy to work with the U.S. if its businesses can reciprocate.

Peru Follows the Money to China

June 17th, 2024

June 17th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at Peru’s pursuit of Chinese investment:

This entry was posted on Monday, June 17th, 2024 at 6:44 am and is filed under China, Peru. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.