November 13th, 2020

Via The Diplomat, an article on disappointing rail freight use on China’s Iron Silk Road:

Containerized rail freight transport under China Rail Express (CR Express) between Europe and China is one of the flagship projects of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However these rail links have been in development since 2011, predating the BRI. China’s co-optation of this transcontinental rail freight development was part of a grander policy vision of an Iron Silk Road to service its new Silk Road Economic Belt, the overland portion of what has come to be branded the BRI more broadly.

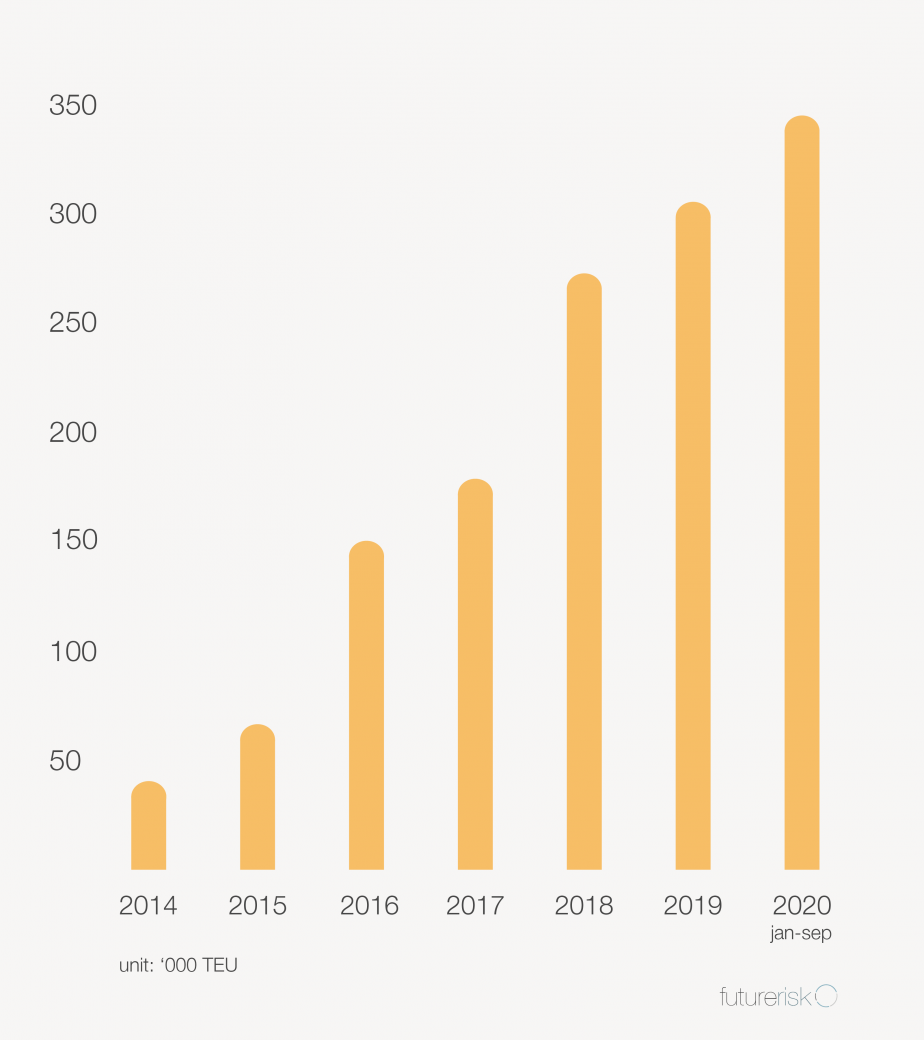

Both academic analysis and news media report a rapidly growing number of trains. We calculated the amount of trains arriving in Europe using open source Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. We compared these figures with hand tallied figures from China’s state media reports of the number of trains leaving China for Europe. We found serious discrepancies between the two figures.

For example in 2017, Chinese state media reported around 3,211 intercontinental trains leaving China for Europe. However Eurostat only recorded 1,793 arriving. Even accounting for some trains being joined together to form longer ones for the Alashankou/Dostyk (Kazakhstan) to Ma?aszewicze/Brest (European Union) leg, this still leaves serious discrepancies in China-Europe rail freight accounting. We would expect to find similar discrepancies in China-Central Asia rail lines.

Both popular media and academic literature have also focused on growth in the containerized rail freight network in China, Europe, and Central Asia. But containerized freight trains are a tiny proportion of railway traffic both in the EU and China. And China’s new CR Express system is not the sole intercontinental rail service, with many European car manufacturers running express services between China’s industrial northeast and Europe.

The CR Express intercontinental containerized rail freight system was deployed in 2016 by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) as a development plan and consolidation policy. The aim was to bring together the disparate Eurasian rail services offered by local governments, rebrand them into a single product, and help to coordinate the national intercontinental rail system. The two new Eurasian rail classes introduced to China’s domestic rail governance under CR Express were China-Europe Class and China-Central Asia Class.

However integrating intercontinental rail classes into the China domestic rail system faced bigger obstacles than any possible geopolitics surrounding the development of a Eurasian rail corridor network. Rail freight has been declining as a proportion of China’s domestic modal split since 2011 as a result of shrinking demand for coal. This is the major domestic policy change driving the fundamental dynamics of China’s international rail transport policies.

This shrinking coal transport demand does create new capacity allowing an alteration of the axial corridor utilization within China’s domestic rail system to develop a policy of West-facing rail freight along the New Eurasian Land Bridge. However, there remain many domestic institutional bottlenecks to development. Four major domestic hurdles that impact the CR Express intercontinental rail freight system are the lack of intermodal hubs, poor seaport connections, underdevelopment of containerized freight, and undeveloped intermodal corridors.

China has few intermodal hubs. “Intermodal” refers to freight carriage across several types of transport, for example a combination of rail, road, ferry, or ship. There are only 39 major intermodal hubs in China that handle containerized rail freight. In comparison, there are 385 intermodal rail terminals in the European Union. This is partially a result of rail freight receiving little government policy attention through the high-speed passenger rail priority period of the past decade. Industrial transport infrastructure is also poorest in the Western and Central China provinces where the CR Express rail freight terminals are located, meaning rapid development of intermodal hubs is needed.

Poor Seaport Connections

Maritime terminals are also underdeveloped and not ready for rail-sea intermodal operations. In 2010 only 10 of China’s 135 government approved ports were using rail-waterborne intermodal transport operations. The promise to Kazakhstan for being the transit corridor for CR Express was sea access via the Lianyungang port in northern Jiangsu. But before expanding its container transport network to Europe and Central Asia, China has immense work to do to upgrade its containerized rail cargo systems and their poor port connections. For example a 2010 study calculated that only 1.3 percent of the total maritime container output was moved through ports by rail.

Underdeveloped Containerized Freight Systems

Many of China’s existing domestic rail freight corridors were developed to maximize bulk coal carriage or other dry-bulk commodities such as iron ore. This meant that containerized rail freight transport is severely underdeveloped, as bulk carriage infrastructure was preferentially developed. Existing domestic rail networks are also tangled, unreliable, and still mostly optimized for south-north carriage, not east-west carriage. The institutional legacies of these built-for-coal bulk rail corridors have left domestic containerized cargo domestically underdeveloped, and not ready for internationalization.

Undeveloped Intermodal Corridors

Without intermodal hubs, rail-seaport connectivity, or established containerized freight systems, it is difficult to establish intermodal rail freight corridors. In 2011 five freight rail corridors between the inland and maritime ports were established. But in 2015 these corridors transported only 1.54 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), whereas China’s sea ports handled 189 million TEUs in the same year. The total from all intermodal rail corridors carried only 0.8 percent of the containers handled by maritime ports. This means that both domestically and internationally, the inland intermodal corridors for containerized rail traffic within China remain underdeveloped.

Despite the national NDRC plan, most prominent international rail freight services have been developed by local governments. These trains receive state subsidies, not only at the national level, but also from the provincial and prefectural governments. The subsidies cover 30-50 percent of total transport costs, therefore it is highly questionable whether even the current volume of transport can be sustained. As the national subsidies are due to be phased out, it is unclear what burden the local governments are prepared to bear to ensure the rail lines stay operable.

Consider that inbound rail freight to Europe from China was actually higher before the introduction of CR Express trains or the Belt and Road policy. According to European Union Directorate-General for Trade, export/import tonnage between the EU and China by rail has grown in recent years, but it was higher a decade ago. This without any Iron Silk Road policy or media hype.

The reality is that there is simply too small a throughput for the China-Europe rail bridge to have any meaning for either Europe or Central Asia. As a percentage of intra-China or intra-European rail trade, the intercontinental rail freight ratio is minuscule. Coupled with deficiencies in China’s domestic containerized rail cargo infrastructure and the unending dominance of maritime container transport, the potential development of a viable Iron Silk Road once subsidies are removed is, on current evidence, beyond weak.

Ultimately, we find the data unconvincing that the China-Europe CR Express rail class has long-term structurally transformative effects on host economies in Europe, or China. For Central Asian economies, given maintained levels of Chinese government subsidies, the CR Express project is probably worthwhile given the lack of maritime transport alternatives.

However for CR Express to improve and expand, China-side subsidies need to be transparent, legal standards, contracts, and other logistics factors need to be integrated to European standards, host economies need to understand which levels of Chinese government they are dealing with, and what their political and economic risk exposure is in engaging with the CR Express system.

However the wider problems of China’s intercontinental rail ambitions remain not economic but political. For the rail policy to have been successful, China’s CR Express policy should have served both Eurasian and European interests, not just China’s. Russia’s many failed or stalled economic development and political expansion projects into Eurasia should have been a history lesson. China’s CR Express may soon join the industrial graveyard of this Eurasian economic policy history.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.