Central Asia has become more geopolitically important lately – not just as the underbelly of its economically challenged and politically isolated neighbor, Russia, but also as a transit hub that links China to Europe and as a supplier of raw materials that will fuel strategically important industries in the future. However, the geopolitical features and problems endemic to the region make it unlikely Central Asia will realize its full potential anytime soon.

Outside interest in Central Asia owes much to its natural resources. It is awash in oil and natural gas and rich in rare earth minerals like monazite, zircon, apatite, xenotime, pyrochlore, allanite and columbite, which are essential in high-tech manufacturing. It is also home to an abundance of scarce strategic resources: some 40 percent of the world’s manganese ore reserves, 30 percent of its chromium, about 13 percent of its zinc and 9 percent of its titanium. About one-fifth of all known uranium deposits are located in Central Asia, not to mention a ton of potential deposits that have yet to be developed.

Unsurprisingly, Central Asia has been mined for decades – from within and without. The Fergana Society for the Mining of Rare Metals dug up the first uranium ore in the early 1900s, and the Soviet Union accelerated materials development after it became a nuclear power. The fall of the Soviet Union would later wreck the regional mining industry as investment evaporated and specialists fled the region en masse. This at least partly explains why, after they gained independence, many former satellites in the region maintained a policy of neutrality: They needed as much funding from as many countries as possible to prop up their only reliable source of revenue. To some degree, the policy worked. By the late 1990s, Australian, Chinese and Canadian companies were all conducting exploratory work in Central Asia, but insufficient demand and political instability kept investment in check.

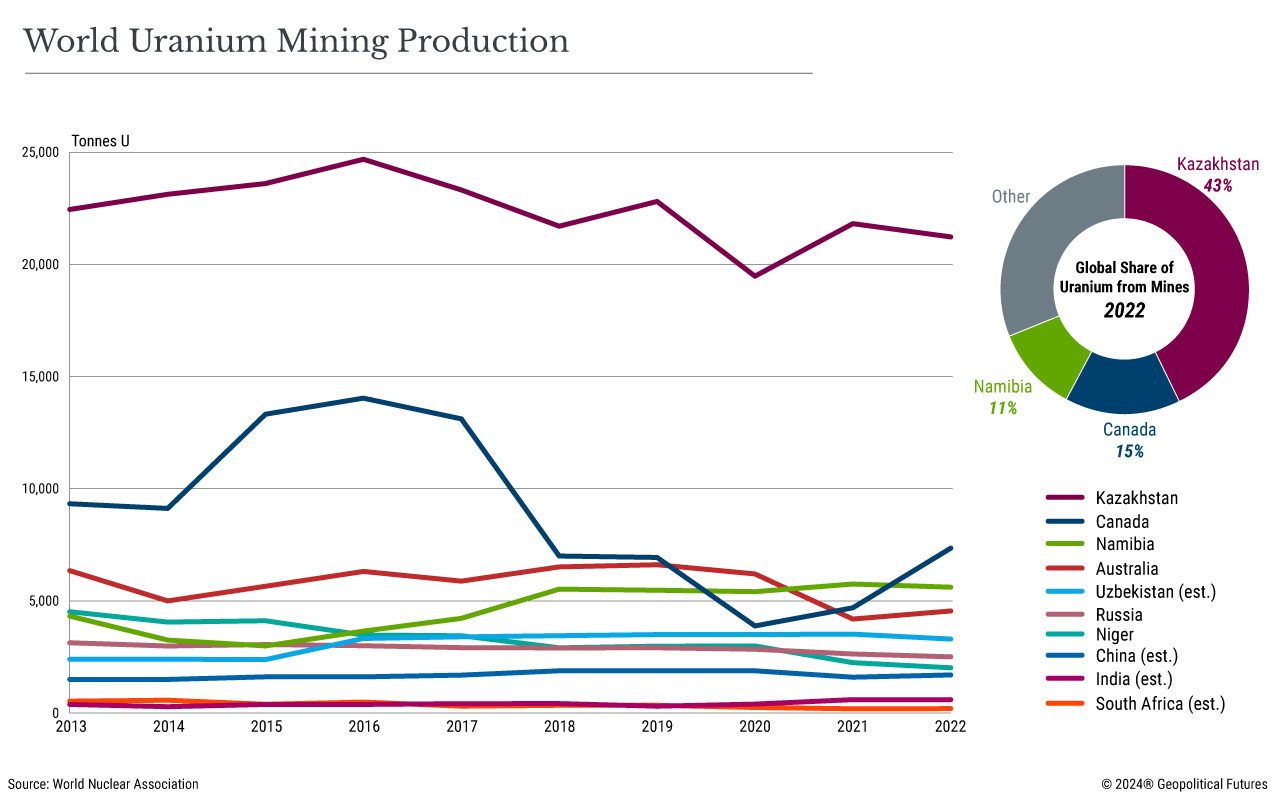

The global push for green energy and the near-exponential demand for electronics (civilian and military alike) has piqued investor interest yet again. Uranium has been the biggest beneficiary. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are the region’s top producers and exporters, and their biggest customers are China, Russia, France and the United States. Several foreign companies – Canada’s Cameco, Russia’s Rosatom, Energy Asia Holdings, France’s Orano and the China General Nuclear Power Group – have become miners and investors in Kazakhstan, which some argue could compete with the current global leader in rare earths and scarce materials: China. This would be good news for Kazakhstan, of course, but it would also be a welcome development in Europe and the United States, both of which are heavily dependent on China for rare earths and as such are looking for alternatives.

Western companies are especially active in investing in scarce materials. The United Kingdom’s UKTMP International Limited and Ferro-Alloy Resources Limited have operated in Kazakhstan for years, and new deals happen every year. In 2023, Britain’s Maritime House signed an agreement with Kazakh producer Zhezkazganredmet, and in early 2024 Kazakhstan and the U.K. signed a roadmap for cooperation on critical minerals, which involved the creation of joint ventures. Also in 2023, French President Emmanuel Macron toured the entire region in pursuit of an agreement to increase uranium supplies for nuclear energy.

Yet there is still a risk that the development thus far won’t be enough to make Central Asia the global center of rare earth production. Largely that’s because much of the industry is underdeveloped for a variety of reasons.

One is geopolitical. The policy of neutrality is essential for Central Asian nations, which have no desire to be politically dependent on a larger power again. Through diversification of goods and relationships alike, these countries will work with virtually anyone in order not to alienate anyone and to prevent any one country from monopolizing their markets. Being fair-weathered is important for economies like Central Asia’s that are maturing but still developing and need to avoid conflict at all costs. Naturally, this is easier said than done. It is in the interests of China, for example, to keep Western countries out of Central Asia so that it can maintain its position as the biggest supplier of rare earths in the world. Beijing is even concluding bilateral agreements to develop Central Asian deposits as a way to increase its market share. It is not looking for another competitor. (Russia, which is sometimes a China ally, is acting similarly, strengthening cooperation in the development of scarce resources to expand its presence in a critically important region.)

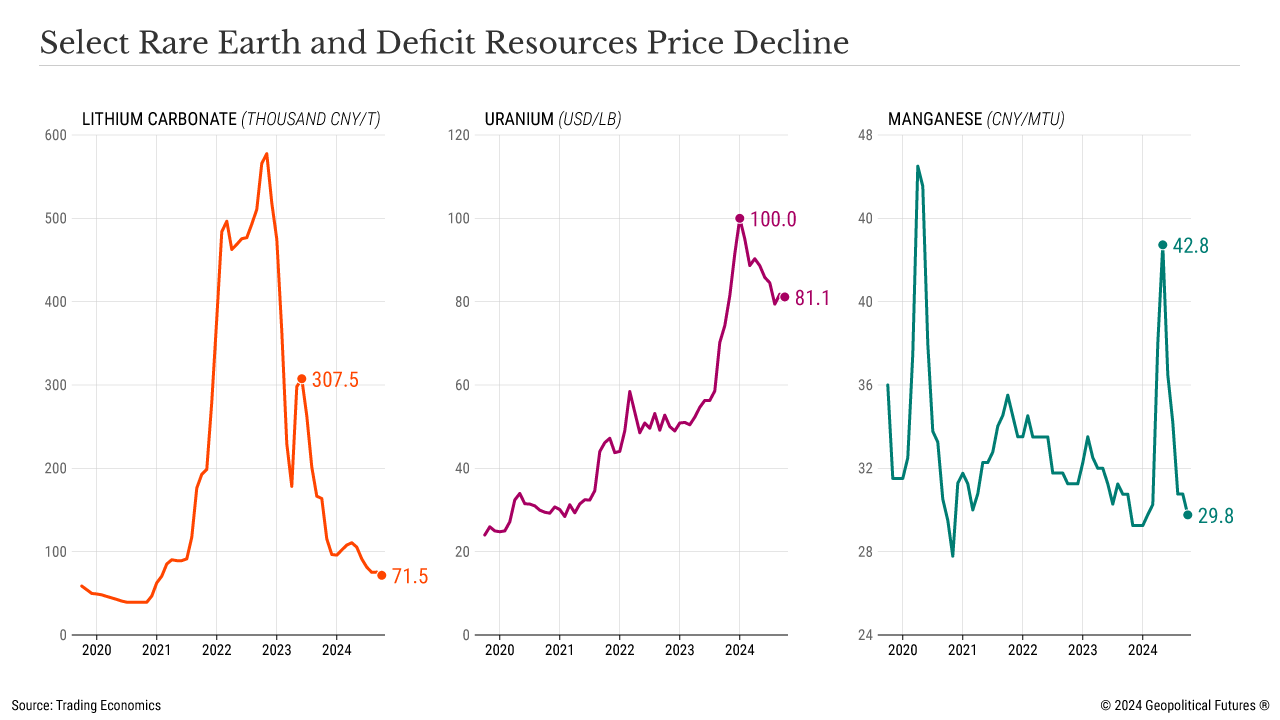

Another reason is economic. Surprisingly, the extraction of rare earth resources isn’t always hugely lucrative, so investors aren’t always as excited as Central Asia wants them to be. And building the capacity to produce rare earths is wildly expensive (even more so in countries like Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan that have difficult terrain). Kazakhstan has yet to decide, for example, whether it will extract and process lithium on its own or with foreign partners – and whether it will try to do so at all. The government does not expect lithium to generate as much money as oil does, so it is considering buying lithium from China to use in the production of high-value-added goods. This explains why some Chinese companies have started construction on an electric and hybrid car plant in Uzbekistan and why South Korea’s Global Solar Wafer plans to create a solar panel production facility in Tajikistan’s Khatlon region. Moreover, the mining industry is cyclical by nature, so there’s no reason to expect the price of rare earths to stay high forever. Investors are thus still skittish about Central Asia, and their uncertainty has prevented the region’s governments from fleshing out the legal frameworks needed to ensure investment and insure risks.

There’s simply not much evidence to suggest rare earths are a sure bet. Over the past few years, they helped Kazakhstan increase state revenue, but the increase was due to higher prices, not higher production or share. Kazakhstan even had to adjust its projections for uranium production in 2024 because of difficulties obtaining sulfuric acid, an important material in uranium mining. And this is to say nothing of how increased domestic demand could undermine productive capacity. Today, countries like Kazakhstan don’t use many rare earths for themselves. But these countries also tend to experience chronic electricity shortages, which compels them to search for other sources of power like renewables and nuclear – sources that require the use of rare earths.

The final reason Central Asia may be unable to achieve its potential is logistics. The region is almost entirely landlocked. It is squeezed between Russia and China such that it lacks direct access to logistic hubs and ports, so if the U.S. and Europe want to wean themselves off Russian and Chinese exports, they still have to deal with Russia and China as transit countries. The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, which leads to Europe, is technically viable but has an extremely small capacity that is already laden with container transportation of petrochemicals, ferrous and non-ferrous metals, coal, ferroalloys and agricultural products. Its expansion requires significant funding and probably the participation of China, which is unlikely to undermine its own influence in the rare earth metals market.

Central Asia’s potential in the rare earths market is high. The obstacles to realizing its potential are not insurmountable, but they will make development of this industry long and difficult. Geopolitically, it’s still best to think of Central Asia as a source of diversification for major players rather than a player itself.

Rare Earths and Rare Opportunities in Central Asia

October 29th, 2024

October 29th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at Central Asia’s rare earths potential:

This entry was posted on Tuesday, October 29th, 2024 at 3:37 am and is filed under Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.