Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, Africa’s Sahel region is experiencing security problems and surging anti-Western sentiment that could prove an opportunity for China, analysts say.

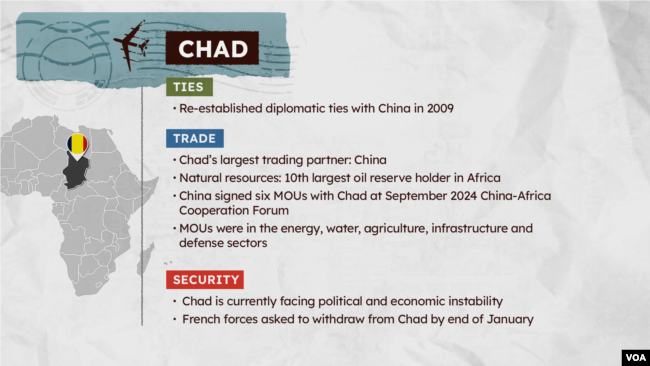

China’s top diplomat was in the volatile Sahel last week as a part of his weeklong trip to the continent, where he pledged military aid on a visit that happened to coincide with an attack on the presidential compound in Chad.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit also came amid a spat between France and its former African colonies.

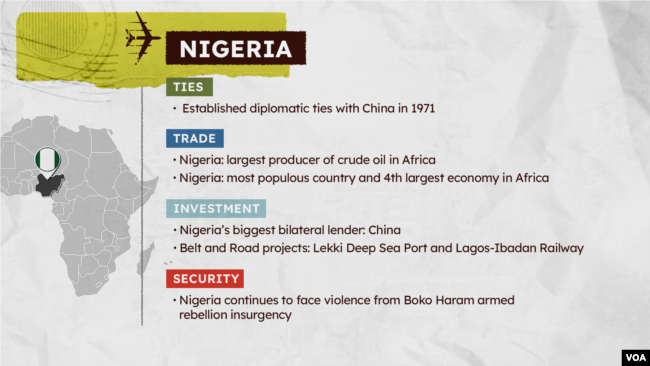

In Nigeria, on the last leg of what has become a regular January trip to Africa, Wang said China would help train 6,000 troops and 1,000 police officers across the continent. Additionally, he pledged $136 million in military aid to the region.

His pledge was a reiteration of Beijing’s promises at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September. But the choices of countries on his itinerary, including Chad and Nigeria, were telling, experts said.

“Wang’s focus on military aid and training, and the choice of countries to be visited, is in line with China’s new focus on defense diplomacy as opposed to the purely economic and diplomatic engagements that used to characterize Chinese engagement with the continent a decade ago,” Darren Olivier, director of the conflict research consultancy African Defense Review, told VOA.

Both Chad and Nigeria are battling insurgencies, and just a few hours after Wang met with Chadian President Mahamat Idriss Deby – who seized power in a 2021 coup – Deby’s compound was attacked by armed men. The attack failed, but the incident “emphasizes the insecurity” in the region on which China could be looking to capitalize, said Alex Vines, Africa program director at Chatham House.

“There is a mercantilist, commercial element to Wang’s trip, which is to look at where to expand on market share, and Nigeria and Chad are very much in the market for defense sales and diversifying their security partnerships,” Vines told VOA.

In fact, China has already surpassed Russia as the top arms supplier to sub-Saharan Africa.

Oluwole Ojewale, a Nigerian researcher with the Institute for Security Studies, said Nigeria has had trouble in the past buying weapons from the U.S. due to alleged rights violations, which has prompted it to look elsewhere.

“For the case of Chad and most countries who are decoupling from the France security partnership … it is almost expected that they also need to look for other international partners that can provide some form of help in terms of armaments, in terms of training,” Ojewale said of the Chinese announcement.

Macron raises ire

Chad in December became the latest Sahel country to kick out French troops that had been operating military bases in the country for years, following the lead of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. Senegal and Ivory Coast have also now asked French forces to withdraw.

The trend comes amid rising anti-French sentiment in a region that has been dubbed Africa’s “coup belt” for the number of military takeovers in recent years. French President Emmanuel Macron heightened such sentiment last week when he said France’s former colonies “forgot to say thank you” for Paris’ security efforts in West Africa, adding that “none of them would be in a sovereign country today if the French army had not been deployed in this region.”

The U.S. has also been made to pull out of the Sahel, with Niger demanding Washington withdraw about 1,000 troops last year and close its largest drone base in Africa.

The U.S. has been struggling to maintain influence in the region, where it had been supporting counter-terror efforts for years. The Pentagon is currently looking at maintaining a smaller force presence in the region.

Some West African countries, such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, have turned for help to Russia, which publicly emphasizes its lack of colonial history. China takes a similar tack, positioning itself as a fellow “Global South” developing country that doesn’t preach to Africa on human rights or other issues.

Of Macron’s “clumsiness,” Vines said, “China will kind of capitalize on it … and the Chinese will privately point out, look, you know, this is what’s different from us.”

Paul Nantulya, a China analyst at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, noted that China has recently become bolder in taking advantage of the French vacuum by delivering batches of high-end security equipment to Sahel countries over the last 15 months.

“And at the FOCAC summit, the representatives of these military regimes were received very, very well in Beijing,” he said, adding that they also visited weapons manufacturers during their time in China.

Filling a vacuum

At FOCAC, China also emphasized its Global Security Initiative (GSI), which was proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2022 as an alternative to the existing world order in terms of solving conflicts and ensuring peace. China’s vision of a foreign security policy includes seeking “the biggest common denominator and the widest converging interests, rather than create closed small circles or reshape the existing international security order.”

While the initiative may signal China’s desire to play a bigger role in international politics, Cobus van Staden, a China researcher with the South African Institute for International Affairs, said Beijing is anti-interventionist and while it might provide training, it’s not going to commit to being a security provider itself.

“Overall, what struck me about the comments was that while they were talking about this kind of military cooperation, Wang was always framing that under the Global Security Initiative which focuses on self-sufficiency rather than external security provisions,” he told VOA.

Deborah Brautigam, director of the Chinese Africa research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, echoed this.

“Military aid and training are low-key, low-cost forms of support that also help open markets to Chinese arms exports. They’re opportunistic and unlikely to be a pathway into the stationing of troops or deeper military engagement,” she told VOA.

Christian Geraud Neema, Africa editor at the China-Global South Project, said he thinks China will stay away from getting directly involved in African crises to “avoid any blowback in case of failures.”

“When speaking with decision-makers on the continent, many have a hard time telling you what China’s GSI is about and how concretely it can fit to their context,” he added. “So many of them consider China an easier option for military equipment than anything else.”

Sahel Vacuum Provides Opportunities For China

January 18th, 2025

January 18th, 2025

Via VOA, a report on how the Sahel vacuum provides opportunities for China:

This entry was posted on Saturday, January 18th, 2025 at 7:00 pm and is filed under Chad, China. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.