October 4th, 2018

Courtesy of The Economist, an interesting article on South Korea’s investment interest in North Korea:

SHIN HAN-YONG likes to think of himself as a pioneer. “We had the spirit to see potential where others didn’t,” says the South Korean businessman. Shinhan, his fishing-gear company, was among the first to begin production in the Kaesong industrial complex, a special economic zone just across the border with North Korea, when it opened in late 2004. Mr Shin had a supervisory role at the complex until it was abruptly shut down in February 2016 following a nuclear test by the North. He still feels bitter about the closure. “Nobody asked us before they closed it,” he complains. “We were hostages to politics.”

But since the spring Mr Shin’s bitterness has been sweetened by renewed hope. In April, Moon Jae-in, South Korea’s president, and Kim Jong Un, North Korea’s dictator, signed an agreement in which they vowed to revive inter-Korean ties. Mr Moon has since outlined ambitious plans for infrastructure investment across the peninsula, including the revival of road and railway links between the countries.

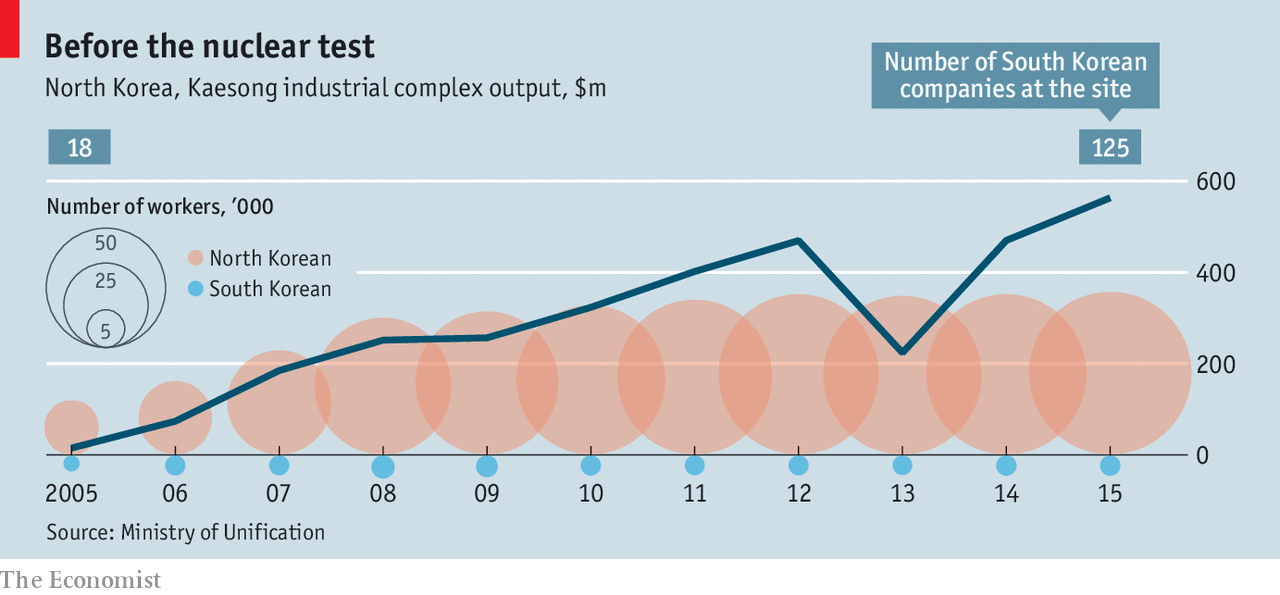

That has set off a flurry of activity by South Korean firms hoping to win business. When Mr Moon went to Pyongyang this week for his third summit with the North’s despot, Mr Shin went along as part of a delegation of business leaders. Executives from the chaebol, as South Korea’s big conglomerates are known, also went—among them Lee Jae-yong, de facto head of Samsung. The hope is that Kaesong may resume its activities, which had become substantial before its closure (see chart), and that dozens of other recently designated “economic development” zones in the North may accept foreign investment.

Several chaebol have task-forces preparing re-entry into the North Korean market. Among them are Lotte and Hyundai, both involved in building and running the Kaesong complex, and KT, which hopes to bring satellite and other communications technology to the North.

Financial services are also seen as a promising market. Several South Korean banks this summer launched products aimed at potential customers in the North, such as a trust fund that could allow North Koreans to inherit money from their Southern relatives. One bank said it was considering opening a branch in the Northern tourist resort of Mount Kumgang if sanctions are lifted. “They are all gearing up so they have a first-mover advantage once conditions are right,” says Kim Byung-yeon of Seoul National University.

That makes sense, on paper at least. Right next door and with no language barrier, North Korea has the potential to become an important market for South Korean firms. Heavy industry and construction companies, struggling with slowing demand at home, are attracted by its need for infrastructure investment, which is enormous—worth at least 50trn won ($45bn), according to one estimate. The North’s extremely low wages make it an attractive destination for business seeking to manufacture for export to other countries.

Yet high hurdles remain. Sanctions from the UN, which prohibit any substantial economic engagement with the North, are unlikely to be lifted until talks about denuclearisation go further. Even then, the path to profits is likely to be a long one. Officially North Korea still bans private property, though there are signs that this stance is softening. Investors have no way of making sure that contracts are honoured.

Past experience is not encouraging: the closing down of Kaesong left the 125 companies that had operated there with losses of around 1.5trn won. North Korea never returned the assets, and the South Korean government has compensated the firms for only around a third of these losses (they are hoping to recover more once the complex reopens). Orascom, an Egyptian company that built North Korea’s Koryolink mobile network, never managed to repatriate its profits from the project and, in effect, lost control of its majority stake three years ago.

If the political situation improves sufficiently to allow fresh investment, it will probably be limited for years to special economic zones, reckons Seoul National University’s Mr Kim. North Korea will not allow foreign firms to invest just anywhere. Companies would still have to work with the two governments to establish rules on property rights, repatriation of profits and mechanisms for settling disputes. The South Korean state is likely to have to put up “a lot of taxpayers’ money to kick-start investment and reassure private companies,” says Mr Kim. It will need, for example, to show that it will pay compensation to firms if things go wrong again.

Advocates of the Kaesong complex claim to be involved in more than just a business venture, however. “We want to bring the two Koreas closer together again,” says Mr Shin of Shinhan. “Profit is not the only motive.”

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.