February 13th, 2011

Via The Oil Drum, a look at how the division of Sudan may affect oil production from that region:

“The disruption that began in Tunisia is continuing in Egypt, with changes also starting in countries such as Jordan and Yemen. And in the midst of this turmoil, the (finally) democratically dictated separation of Sudan into two separate countries is moving towards the July 9th separation date. At that time Southern Sudan will divide from the North. Sudan has only been selling its oil on the world market since 1999 and the transition will impact those exports.

With the hopeful end to the conflicts in the country, there is also now an increasing possibility that the oil and natural gas resources of the two new nations will be developed. Until recently China has been the most active player in the region, but as the results of the vote have become apparent, Russia too is indicating an interest.

Like other players in the world oil market, Russia would like to promote its energy interests in that region. Moreover, it is capable of becoming a serious competitor for both Western and Chinese companies in oil production and power supply. Russia’s clear competitive advantages are its technological experience in developing oil fields in many regions of the world, its investment potential and the absence of any political conditions for energy cooperation. The latter is important both for Khartoum and Juba, the current administrative centre of South Sudan, because after the referendum both sides will have to reconsider the criteria of their independence.

For while China has a 40% interest, Malaysia has a 30% interest, and India in 3rd place with 25% in the current production company. And with the Russians expressing interest, who knows what may transpire.

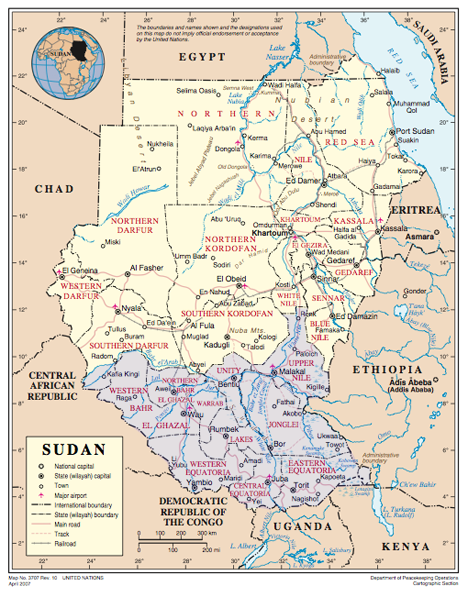

Map of Sudan (United Nations) The blue tone marks the bounds of the South Sudan States.

The EIA notes that in 2009 oil was the major revenue generator for the country, bringing in more than 90% of foreign earnings. Within the country the primary energy source is that of combustible renewables and waste, reflecting the rural, non-electrified population of much of the country. And although BP (as reported by Energy Export Databrowser) suggests that virtually all the oil it produces is exported:

Oil statistics from Export Data Browser, based on the BP review.

The EIA find that there is a significant, and growing, domestic market, that uses a significant percentage of production. Various estimates of the size of the export market (for reasons given below) hover around the FT estimate of around 500,000 bd.

EIA statistics on Sudanese oil production.

The EIA note, as is shown on the graph above, that production and exports developed after a pipeline was run 1,000 miles from the oil fields up to Port Sudan. And it should be noted that while about 75% of the oil reserve (perhaps 6.5 billion barrels) is mainly in the South, that port (map above) is in the North. And as European nations in particular, but also those of the FSU, know from the past, those who control the pipeline can often remain in a position of power. The previous arrangements and actual distribution of funds have been viewed with some suspicion.

Much of this is due to the opacity with which Khartoum’s captured state machinery operates, siphoning as much as 40% of total oil revenue through various forms of mispricing. Meanwhile, though the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of 2005 established that 50% of revenues must be remitted to the Government of South Sudan (GOSS), this share is determined not by volume but sales. Khartoum markets the oil nearly exclusively and determines price as well as volumes exported, with little or no independent monitoring. According to U.K. watchdog Global Witness, major discrepancies of between 9% and 26% have been documented, underpaying the GOSS by as much as $700 million. Little is known of the $7 billion in oil revenues remitted to the South as accountability mechanisms were never factored into the CPA.

That initial agreement is set to expire this July. The pipeline supplies oil to two refineries (at El Obied and Khartoum) that supply the domestic market.

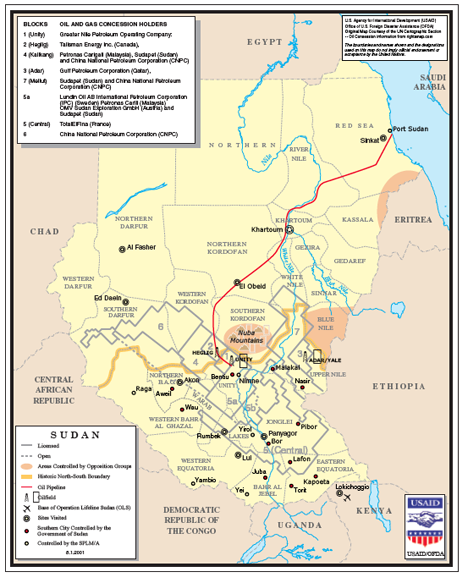

Current pipeline and bid blocks in Sudan (USAID)

One thing that may change this is the construction of s second pipeline, running from the South to Mombasa in Kenya. This would also feed a new refinery proposed for Lamu, which is near Mombasa. However the pipeline would be 870 miles long and have to go uphill to get into the Kenyan highlands, making it quite expensive. An extension of a railway line has been suggested as an alternative. But it now appears that the rail link will go through Uganda, rather than directly to Lamu.

Possible oil routes South from the new capital at Juba.

North Sudan is currently producing about 100 – 110,000 bd of Sudanese total production, but it hopes, by increasing production from the Balila oilfield in South Kordofan from 60 kbd to over 100 kbd, among other gains, to raise this level to 195 kbd by 2012. It has also been exploring for oil offshore in the Red Sea.

Meanwhile exploration in the South is expected to increase, and there are hopes that production might increase to 2 mbd by 2015, from their current estimated production of 450 kbd.

Conditions in the South however are not currently ideal for oil production, even for the Chinese

He said trucks bringing in fuel vital to operations were stopped at 12 illegal checkpoints on one 200km stretch of road alone, each time being charged $300. Waste oil has been set ablaze and workers kidnapped, he added.

These conditions may make China less likely to invest at the scale required for the new transport network. On the other hand China is but one of several partners in production.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.