September 22nd, 2013

Courtesy of The Economist, a look at grocery retailing in Africa:

A SHORT drive along Cairo Road, a clogged artery that runs through Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, affords a glimpse of the progress South Africa’s big grocery chains have made in the rest of Africa. The rather dowdy Shoprite store situated on the busy main road was opened in 1995 and was the firm’s first venture beyond its immediate South African hinterland. Farther along the road is a shiny shopping centre at Levy Junction, which opened in 2011. Its main tenant is Pick n Pay, a long-established retailer in South Africa but a recent entrant to Zambia. Woolworths, an upmarket chain (unrelated to some similarly named firms in other countries), has also opened a store here. So have many other South African retailers.

Where Shoprite has led, others have followed. Its first store was one of eight acquired from a failing state-owed chain. It now looks a shrewd purchase. Zambia’s economy was then a mess but has since grown rapidly thanks to burgeoning demand from China for the copper that Zambia has in abundance. The country’s fortunes mirror those of the continent. Of the world’s ten fastest-growing economies in the past decade, six were African. Formal retailing is in its infancy and is fragmented. The top six retailers in Nigeria, a country of 167m people, account for barely 2% of sales. The continent’s appetite for air-conditioned stores with tiled floors and branded goods seems almost limitless.

The growing demand is drawing investment from South Africa, whose big chains are keen to escape a sluggish domestic market. Sales in Shoprite’s supermarkets in the rest of Africa grew by 28% in the year to June, compared with only 9.8% at home. The chain has 47 new African stores in the pipeline, mostly in Nigeria and Angola, two of Africa’s largest economies. The firm’s boss, Whitey Basson, has said there could eventually be room for up to 800 Shoprites in Nigeria. The seven it already has there sold more Moët & Chandon champagne in the past year than its South African stores combined.

Close to the customer

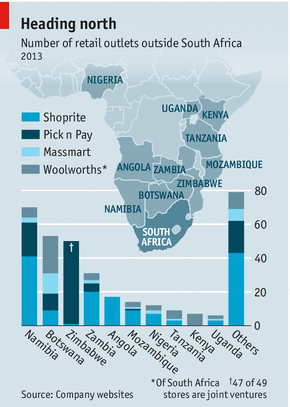

Lots of rich-world firms are pondering how to profit in Africa’s fast-growing bits. The South African retailers have an edge. They are nearby. Stores outside the domestic market are clustered close to home (see map). Shops in Zambia can be reached by lorry in a day from distribution depots in Johannesburg. In-house experts in IT, property management and supply chains are a two-hour flight away.

The chains can also draw on a manufacturing base at home for a range of goods that could not easily be supplied in other parts of Africa. The “back-hauling” of goods to South Africa—fish from Mozambique or strawberries from Zimbabwe—helps to defray the cost of moving stuff the other way, says Dallas Langman, an executive at Pick n Pay. Lengthier supply chains are expensive and precarious.

The South African retailers strive to develop local suppliers in countries they enter. A big slug of sales in Zambia, for instance, is accounted for by staples, such as cereal, meat, vegetables and soft drinks, which can be bought locally. Some toiletries and household cleaners are also made there. Local brands even lead sales in a few categories, says Andy Roberts, the head of Pick n Pay’s operation in Zambia.

Farther from South Africa it is trickier to keep stores fully stocked. Delays at the ports in Lagos mean that it takes 117 days to supply one of Shoprite’s Nigerian stores from its base in Cape Town. However, the paucity of South African stores in east Africa has less to do with supply-chain problems than with the competitive challenge of local retailers. Nakumatt, Uchumi and Tuskys, the three largest Kenyan chains, also have stores in neighbouring Uganda and in Rwanda. All but Tuskys are in Tanzania, where Shoprite has had to close stores. Massmart, another big South African retailer, is said to be in talks to buy Naivas, a smaller Kenyan chain.

To keep growing, the South African chains have to tailor their offering to poor shoppers. A Shoprite in Zambia’s copper belt carries perhaps a quarter of the range of goods of its flagship store in Manda Hill, a posh part of Lusaka, which is said to be the busiest shop in Africa. Three products stand out from the sales figures at the Pick n Pay store nearest his office, says Mr Roberts: a 25kg sack of maize meal, a working-class staple; the bread baked in-store (“not the cheapest”); and bars of Lindt, a luxury chocolate. “That tells you how mixed the customer base is.”

Location, location, location

Store openings also depend on finding suitable sites and property firms to develop them. It has not always been easy. When Shoprite settled on a plot for its first store in Nigeria, it reportedly had three people claiming land rights. All had deeds. Some contractors have got burned doing business in Nigeria and are reluctant to go back. It can take at least 18 months to settle land issues, arrange permits and contracts, and sign leases with tenants before a shovel is used, says Roberto Ferreira, who runs a property fund for Stanlib, an investment manager based in Johannesburg.

Shoprite has more stores outside its home market than its peers, and the boldest plans to open more. Analysts say that being first mover will, for now, give it an advantage. For a start, it will be a while before its profits start to be eroded by increasing competition from other entrants. It can grab the handiest store locations and tie up the best local suppliers to exclusive deals.

But the benefits to the first-mover may not last very long. African cities are growing haphazardly, so a great location today may not be so good in five years. Only now are large sums of money being raised to build lots of new shopping centres: late entrants may find good spots in these malls once they are built. Ports and road links can only get better. “We are in a hurry to get it right, not to plant flags around Africa,” says Richard Brasher, Pick n Pay’s boss, who was hired recently from Britain to revive the retailer.

The South African chains will not have the continent’s growing markets to themselves forever. Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, bought a majority stake in Massmart in 2011 as its route into Africa: its ambitions there, as elsewhere, are unlikely to be modest. Carrefour, a French retailing giant, is dipping its toe into eight African countries in a joint-venture with CFAO, a distributor of cars, drugs and sportswear. Britain’s biggest grocer, Tesco—Mr Brasher’s old firm—lies in wait.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.