Mexico’s economy made headlines late last week when the latest data from the U.S. Commerce Department showed that, for the first time in more than 20 years, Mexican exports to the U.S. surpassed exports from China to the U.S. Mexico’s exports rose 5 percent year over year in 2023, while Chinese exports fell by 20 percent. Though the shift has more to do with the U.S.-China trade war than Mexican policy to goose northbound trade, it would be a mistake to dismiss its efforts entirely.

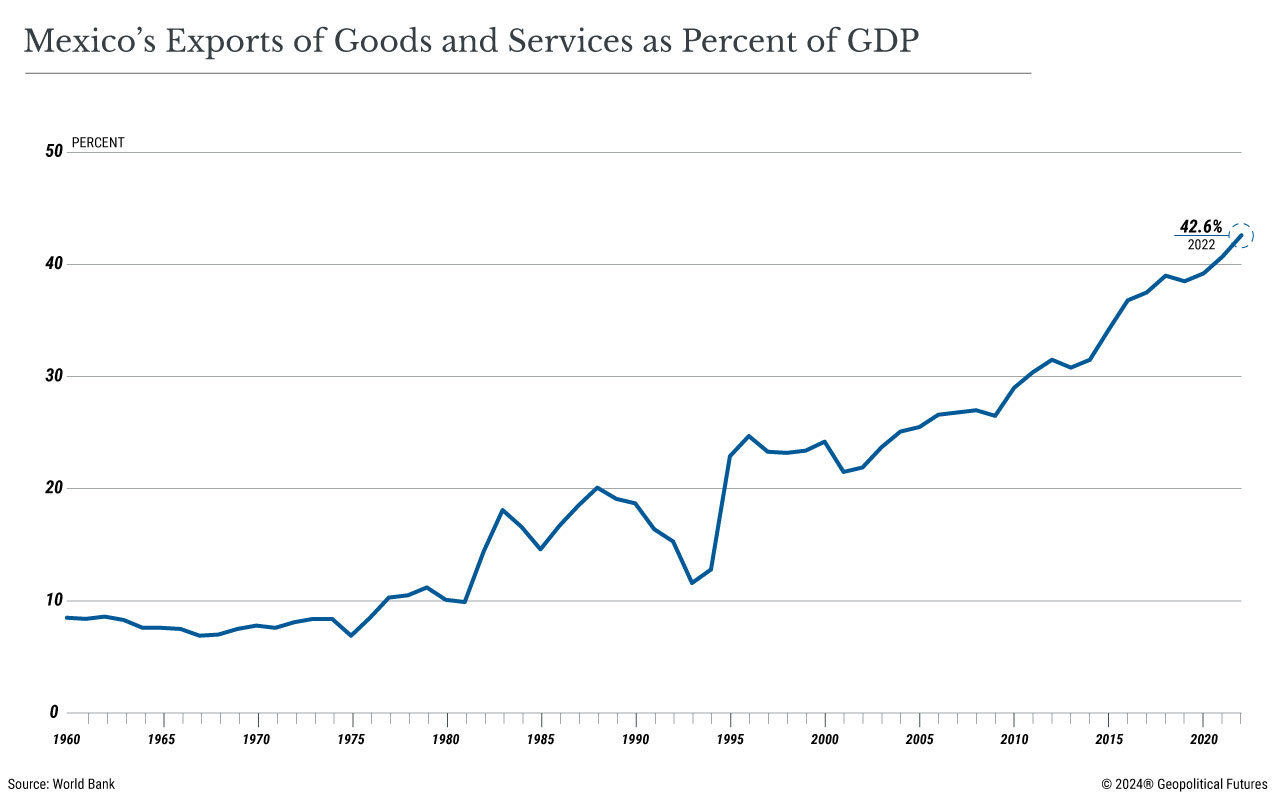

The nature of Mexico’s export problem today bears little resemblance to the country’s export problem 40 years ago. For much of the 1960s and 1970s, Mexico exported primarily oil, which registered less than 10 percent of gross domestic product. Efforts were made to raise this number in the 1980s, but they were largely unsuccessful. By 1994, following three years of negotiations, the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect, boosting Mexican exports as a share of GDP from 12.8 percent to 22.9 percent in only its first year. Over the next three decades, exports reached the equivalent of 42.6 percent of Mexico’s economy.

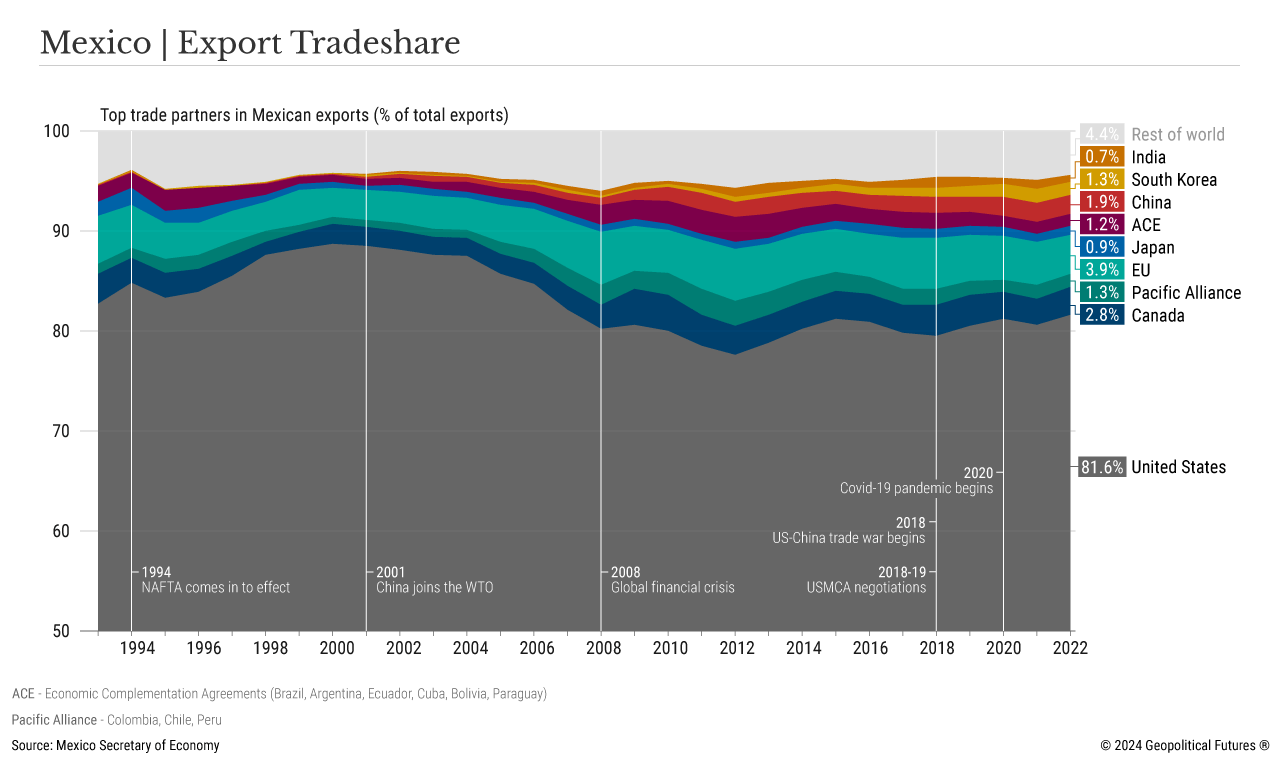

For Mexico City, the problem is that it now has an unwanted dependency on a single revenue stream. By nature, exports depend on external markets, most of which behave in ways outside of Mexico’s control. Moreover, Mexican exports are heavily concentrated in the U.S. market, which accounts for 81 percent of all exported goods. (Services play only a marginal role in total Mexican exports.) Thus, one of the major challenges and goals for the Mexican government is to find ways to grow trade share – particularly exports – with other markets so that it isn’t so vulnerable to the vagaries of a single buyer.

In addition to new trade partners, Mexico would also benefit from diversifying the kinds of goods it exports. Mexico’s top five categories – vehicles, machinery, electrical equipment, mineral fuel and medical instruments – account for nearly 70 percent of all exports. Vehicle production is particularly closely tied to the U.S. economy, and mineral fuel is highly susceptible to price fluctuations.

For the past 20 years, Mexico has experimented with different approaches to seeking new markets. In 2000, the U.S. accounted for nearly 90 percent of all Mexican exports, declining to its current 81 percent only after the 2008 financial crisis. For much of this time, Mexico treated EU markets as alternatives to the U.S. For its part, the EU considered Mexico an attractive destination, thanks in part to its proximity to the U.S., and so in 2000 Mexico and the EU negotiated an economic partnership to help govern trade. Eighteen years later, they agreed in principle to modernize the agreement by removing tariffs on EU food and beverages, allowing more EU services in Mexico and providing greater protection for worker rights and the environment. Mexico has also made several attempts to enhance trade with other Latin American countries with an eye toward positioning itself as a regional economic leader. Thus it engaged in a series of complimentary economic agreements with Mercosur in the early 2000s and created and promoted the Pacific Alliance in 2011. None of these efforts, however, have achieved their desired result.

Mexico has since set its sights on Asia, which has been identified as the home of many untapped markets with high growth potential. The U.S.-China trade war contributed to the growth of trade relations between Beijing and Mexico City. Foreign countries see Mexico as a gateway to U.S. markets and often try to establish business operations there so that goods can more easily enter the U.S. and on better terms. (Washington is extremely sensitive to China’s efforts in that regard.)

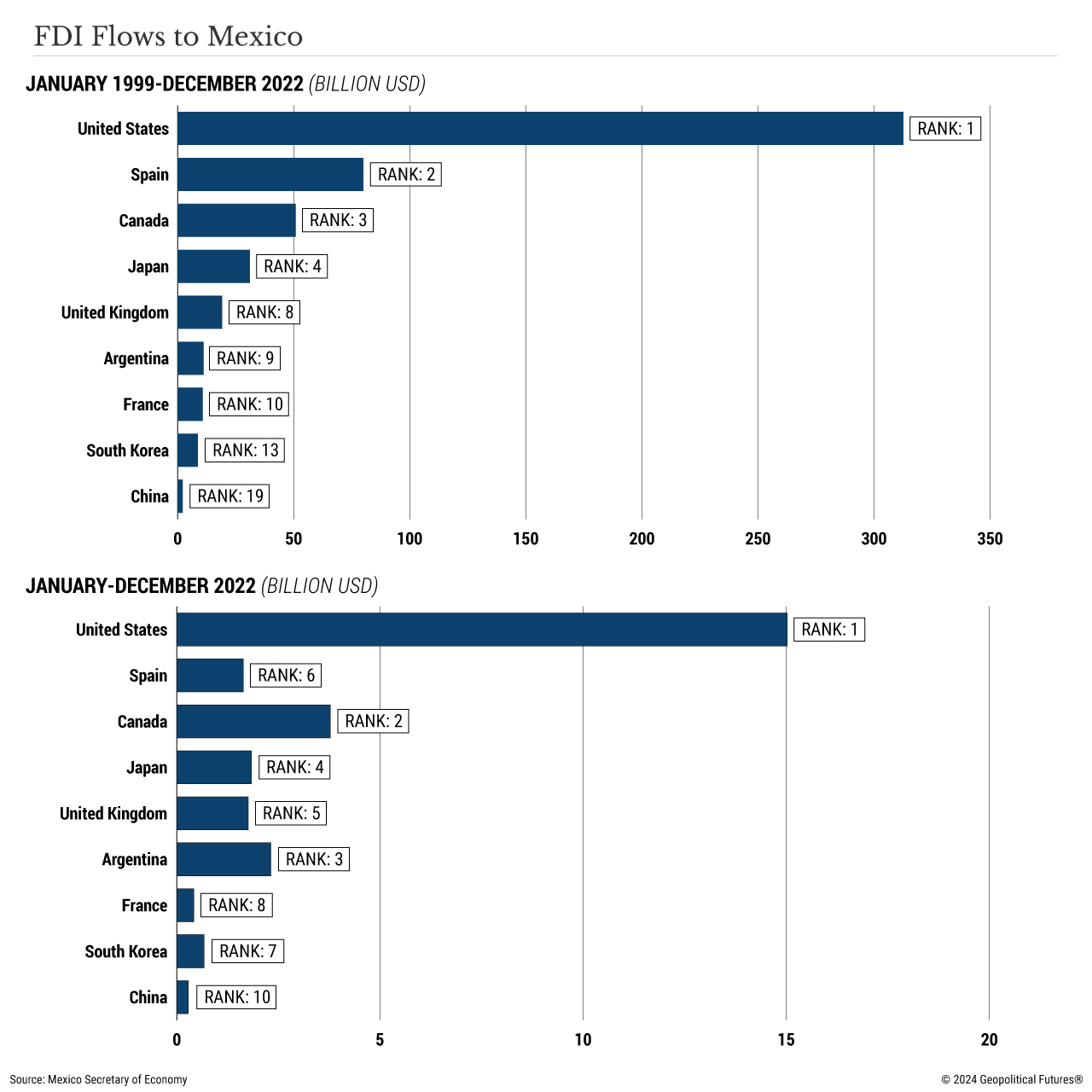

But it’s important not to overstate China’s trade potential. The U.S. is by far Mexico’s largest trade partner, accounting for 61 percent of total trade. China ranks a far second, accounting for a mere 11 percent of Mexico’s total foreign trade, the majority of which consists of importing Chinese goods. The U.S. is also Mexico’s top source of foreign direct investment, accounting for nearly half of all FDI from 1999 to 2022. In fact, in terms of FDI in Mexico, China lags behind South Korea, Germany, Canada, Japan and Brazil. Though Beijing has recently made strategic purchases of mines and ports, and has opened several automobile companies throughout the country, Mexico hosts only about 1,300 Chinese businesses with investments there. (It’s worth noting that Mexico City recently revoked ownership of lithium mines on the grounds that they are a strategic national asset.)

But there is more to Asia than just China, and Mexico is increasingly preoccupied with the continent writ large. It was the first country, for example, to ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2018, even if it already had strong trade agreements in place with many of the other signatories. The CPTPP helped to improve Mexico’s regional standing and bolstered its ties with Japan. Ultimately, Mexico wanted to make sure it had access to new markets that promised strong growth.

Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is a shadow of its former self. While still massive, its ability to invest overseas, fund projects and contribute to robust economic growth in other countries is now in question. Japan and India rank as the world’s 4th and 5th largest economies, while South Korea isn’t far behind (13th). The Japanese and South Korean economies are especially enticing to potential Mexican exporters because they are highly developed, high tech, wealthy and stable, and they are expected to achieve economic growth in the coming years (by developed economic standards, that is). India is seen as just as promising, set as it is to grow an impressive 6.3 percent this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. Not coincidentally, all three countries are security allies of the U.S., so Washington will be less concerned with Mexican outreach there than in China.

Mexico has a long way to go to properly de-risk and diversify its export markets and relationships. Changes in trade flow take time to set in, especially when relations are as asymmetric as they are between the U.S. and Mexico. But that hasn’t stopped Mexico from trying in Latin America and Europe, so there’s no reason to believe it won’t try with Asia either.

The Big Picture of Mexican Exports

February 13th, 2024

February 13th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at Mexico’s exports and recent data that suggest its pivot to Asia may pay off:

This entry was posted on Tuesday, February 13th, 2024 at 11:56 pm and is filed under Mexico. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.