The US’ bid to take on China with the new Imec transit corridor leaves regional powers jockeying for influence. But will it actually be used?

Israel‘s former transport minister was full of hope and optimism when he unveiled his ambitious plan to link the eastern Mediterranean country with the wider Middle East.

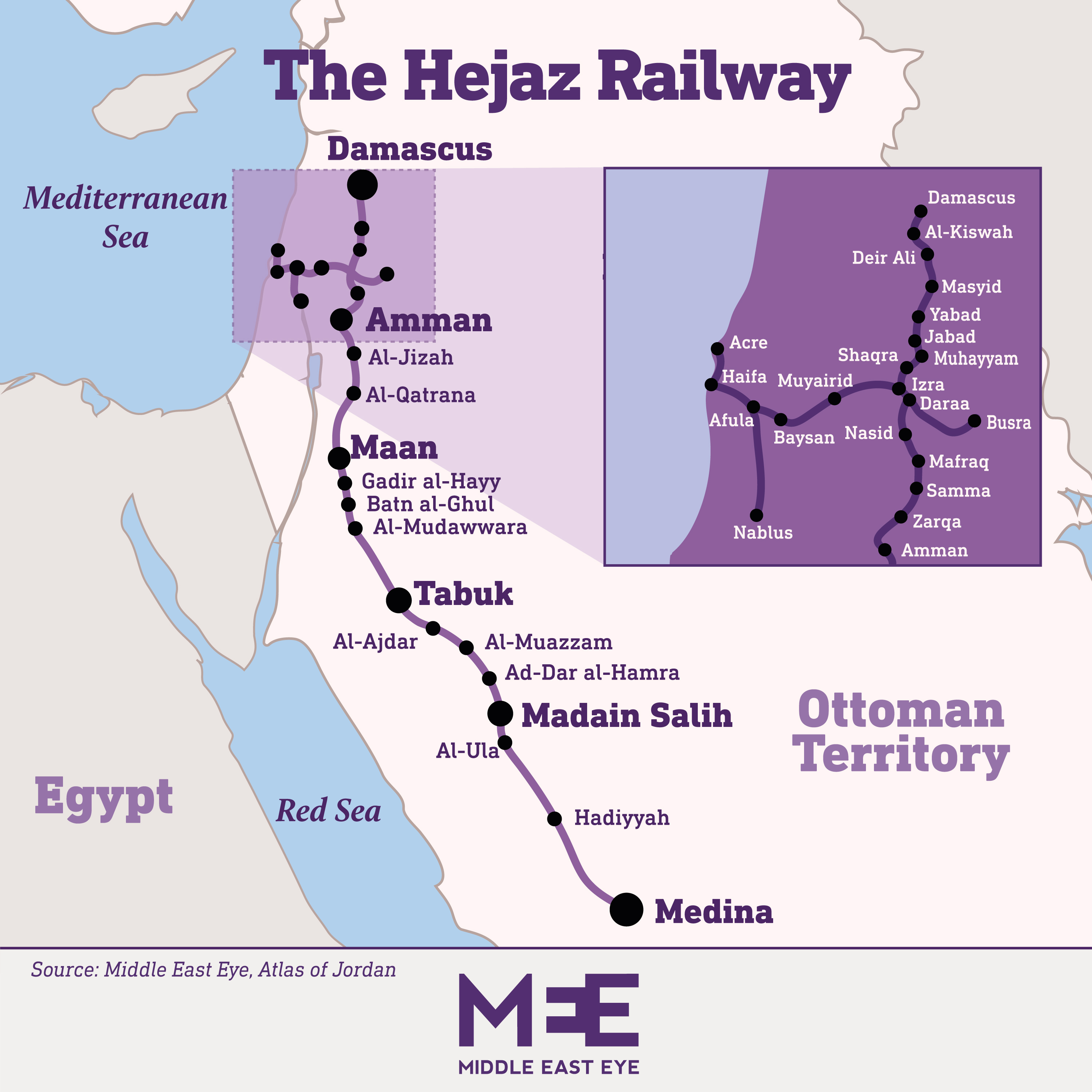

“I want to revive the Hejaz railway,” Israel Katz told reporters back in 2017, invoking the century-old rail line built by the Ottoman Empire that connected the Palestinian port city of Haifa with Damascus, Amman and Madinah.

“This is not a dream,” he exclaimed.

Fast-forward six years and these plans have been brought up once again, albeit on a more grandiose scale.

At the G20 summit in New Delhi, the United States and the European Union said they backed a plan to build an economic corridor linking India with the Middle East and Europe.

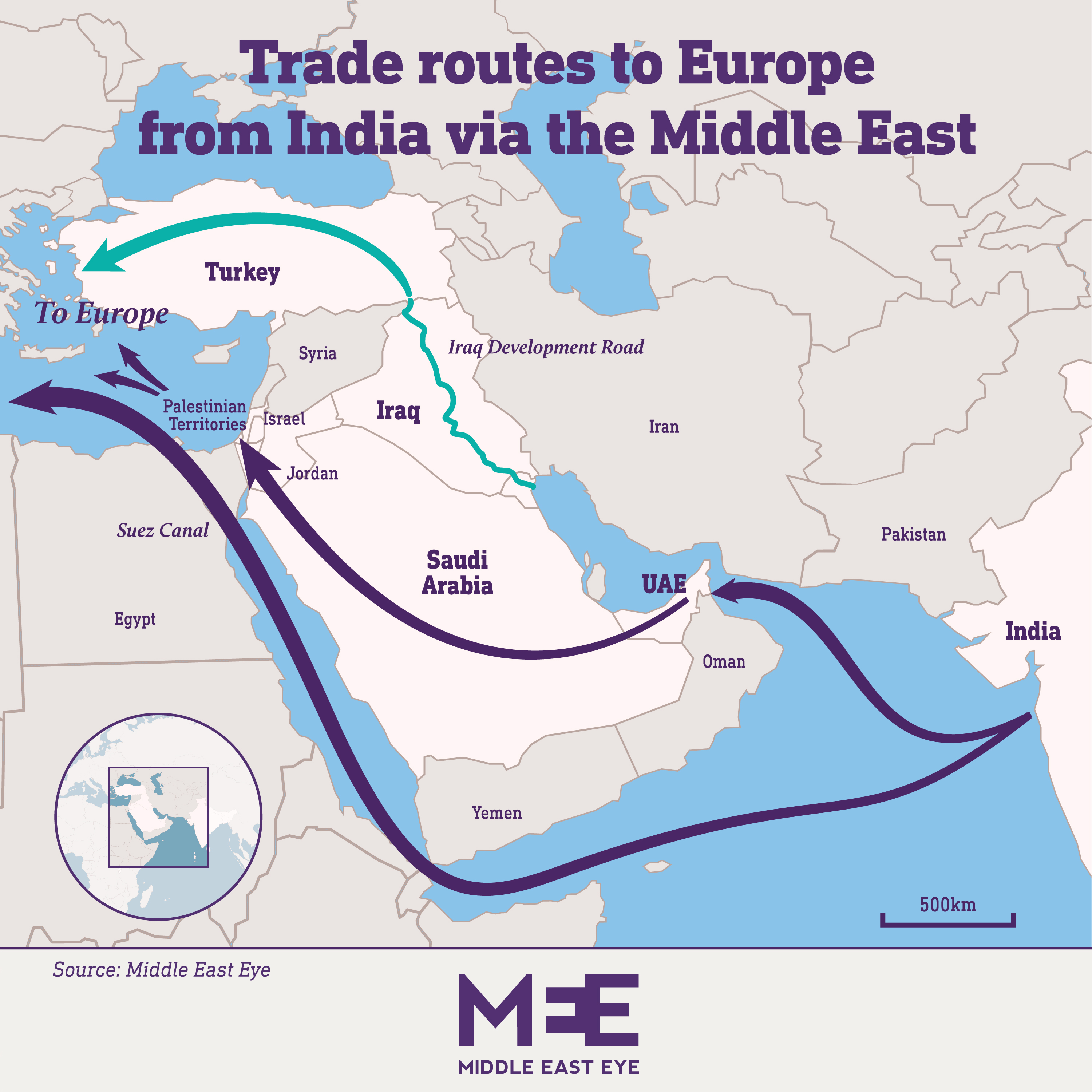

The transport link, dubbed the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, or IMEC, aims to establish new shipping lanes between India and the United Arab Emirates and a freight rail system cutting across the Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel, from where goods can be shipped to Europe.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called the project “nothing less than historic”, adding it would cut transit time between India and Europe by 40 percent.

“It will be the most direct connection to date between India, the Arabian Gulf and Europe,” she said.

Saudi Arabia’s Investment Minister Khalid Al Falih went further, describing IMEC, which will reportedly include electricity cables and clean hydrogen pipelines, as “the equivalent of the Silk Route and Spice Road”.

While the Middle East is no stranger to announcing massive infrastructure projects, many usually fizzle out when they collide with economic and geopolitical realities.

So the comments by Katz, who is now back as transportation minister in Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, underline how some of these plans kick around the region for years without being realised.

A project mooted for decades to lay 2,117km of rail track connecting the Gulf Cooperation Council member states has never fully materialised. But some say IMEC will be different.

Whereas a transit corridor may have been something of a pipe dream just a decade ago, the culmination of the Abraham Accords – together with shifting political and economic reconfigurations in the Middle East, in which new players like China and India have rapidly gained new levels of influence – has created high stakes for such a project to succeed.

“For the US, IMEC aims to check China’s deepening ties to the region,” Jesse Marks, a non-resident fellow on China-Middle East relations at the Stimson Center think tank and a former adviser in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, told Middle East Eye.

“The White House is waking up to the reality that China is all in on the Middle East. This is the Biden administration’s response,” he added.

As Washington looks to reassure its traditional Arab partners about its staying power as they warm up to Beijing, other actors of this vast ensemble bring their own ambitions and anxieties, breathing air into the project.

Energy-rich Gulf states are reconfiguring their fossil fuel-dependent economies. Meanwhile, China’s growing influence comes at a moment in which India, one of Israel’s closest allies, looks to exert itself on the world stage, as both an economic power and a hub for the global south.

Belt and Road Initiative 2.0

Some analysts have described the IMEC as a US-backed alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

A total of 17 countries in the Middle East and 52 in Africa have signed onto BRI, a massive infrastructure project that seeks to connect China with the rest of the world through a series of land, maritime and digital networks.

Since it was first unveiled in 2013, the BRI has helped bankroll a boom in African infrastructure, allowing credit-starved countries to build hydropower projects, airports, roads and railways. But the initiative has also been criticised for its heavy reliance on Chinese labour and ensnaring developing countries with sky-high debt levels. Some say this has allowed Beijing to capture poor states’ strategic assets.

Last month, US President Joe Biden slammed Beijing’s flagship infrastructure project as a “noose and debt” trap.

BRI also faces serious challenges. China’s overseas investments plummeted during the coronavirus pandemic, and the country’s domestic economic woes have continued to hold it back. In terms of spending, BRI activity peaked around 2017 and has been shrinking ever since.

Several European countries have also distanced themselves from the BRI, with Italy reportedly looking for an exit. Meanwhile, in the Middle East, the expectation that BRI could revive the economic prospects of Levantine countries such as Lebanon, Syria and Jordan have failed to materialise.

But the drop in construction and investment is uneven.

BRI is picking up steam in sub-Saharan Africa, according to Fudan University’s Institute of Belt and Road & Global Governance, particularly as China looks to grab strategic minerals. Beijing has also doubled down on investment and construction in energy-rich Middle Eastern states.

“This is BRI 2.0,” Marks said.

“The debt trap diplomacy model everyone likes to talk about isn’t relevant to the Gulf region. China has centralised its deals to countries where it can actually get a return on its money, like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iraq.”

Saudi Arabia and the UAE ranked first and third for the highest construction volume of BRI projects in the first half of 2023, chalking up $3.8bn and $1.2bn respectively. Tanzania was nudged in between at $2.8 bn.

‘Strategic response’

Over the past decade, China emerged as the top customer for Gulf states’ oil. The flourishing energy trade has morphed into a more mature economic relationship.

Saudi Arabia, the region’s largest economy, has been at the forefront of this shift.

In June, China’s Baoshan Iron & Steel signed a $4bn agreement to build a steel factory in Saudi Arabia, a small slice of the $50bn worth of deals the two countries committed to during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Riyadh in December.

MEE previously reported that Chinese businesspeople were flocking to the oil-rich kingdom, shrugging off human rights concerns and western scepticism about the feasibility of mega-projects like Neom.

In some areas of proposed collaboration, projects are already in motion which appear to anticipate the IMEC blueprint.

This week, a landing station in the UAE was announced for a proposed fibre-optic cable eventually intended to link India to Europe that will run across Saudi Arabia and Israel.

The project’s backers include a major Israeli investment fund, and organisations involved include telecoms companies in Saudi Arabia and the UAE and the Gulf Cooperation Council Interconnection Authority (GCCIA), a private company jointly owned by the six states of the GCC.

As economic ties grow, China is making inroads into more sensitive domains, raising alarm bells in Washington.

Autocratic rulers across the Gulf have also binged on Chinese technology, such as Huawei’s 5G. Beijing says it wants to buy Gulf oil and gas in yuan, a move that could dent the dollar’s dominance in world trade.

Meanwhile, Riyadh is reportedly considering a Chinese bid to build it a nuclear power plant. The US believes China is constructing a military facility next door to Saudi Arabia, at a port near Abu Dhabi in the UAE.

China’s biggest diplomatic achievement came in March, when it brokered a deal for Saudi Arabia and Iran to normalise relations. CIA director Bill Burns reportedly told Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman that the US was “blindsided” by the rapprochement.

So whereas IMEC is regularly touted as a response to BRI, David Satterfield, a former State Department official working on the Middle East, argues that the corridor seeks to offer more than an economic alternative to China.

“China has a strategic objective to upend the US-based world order. The Biden administration is trying to come up with a strategic response to counter that,” Satterfield, a director of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, told MEE.

Enter India, Satterfield says.

‘Ties with India beyond oil’

Whereas Washington has looked to reassure its traditional Arab partners about its staying power as they warm up to Beijing, other entities – featuring Saudi Arabia, Israel, the UAE and India – have brought their own objectives to IMEC.

Leaders in Gulf capitals have been charting a path independent from the US on foreign and economic policy.

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE were invited to join Brics, the club of emerging nations that counts US foes Russia and China as members, but also India.

While Gulf states are cosying up to Beijing, they are also building ties with its Asian rival. India is a close runner-up to China as a top buyer of their oil, and it just became the world’s largest country by population.

The UAE in particular was a big advocate for India’s inclusion in IMEC, experts tell MEE.

‘One policy priority in the Middle East is to broaden ties between Washington’s traditional Gulf Arab partners and India beyond oil’

– David Satterfield, former State Department official

“I do want to say thank you, thank you, thank you,” Biden said during IMEC’s rollout, addressing Emirati President Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

“I don’t think we’d be here without you.”

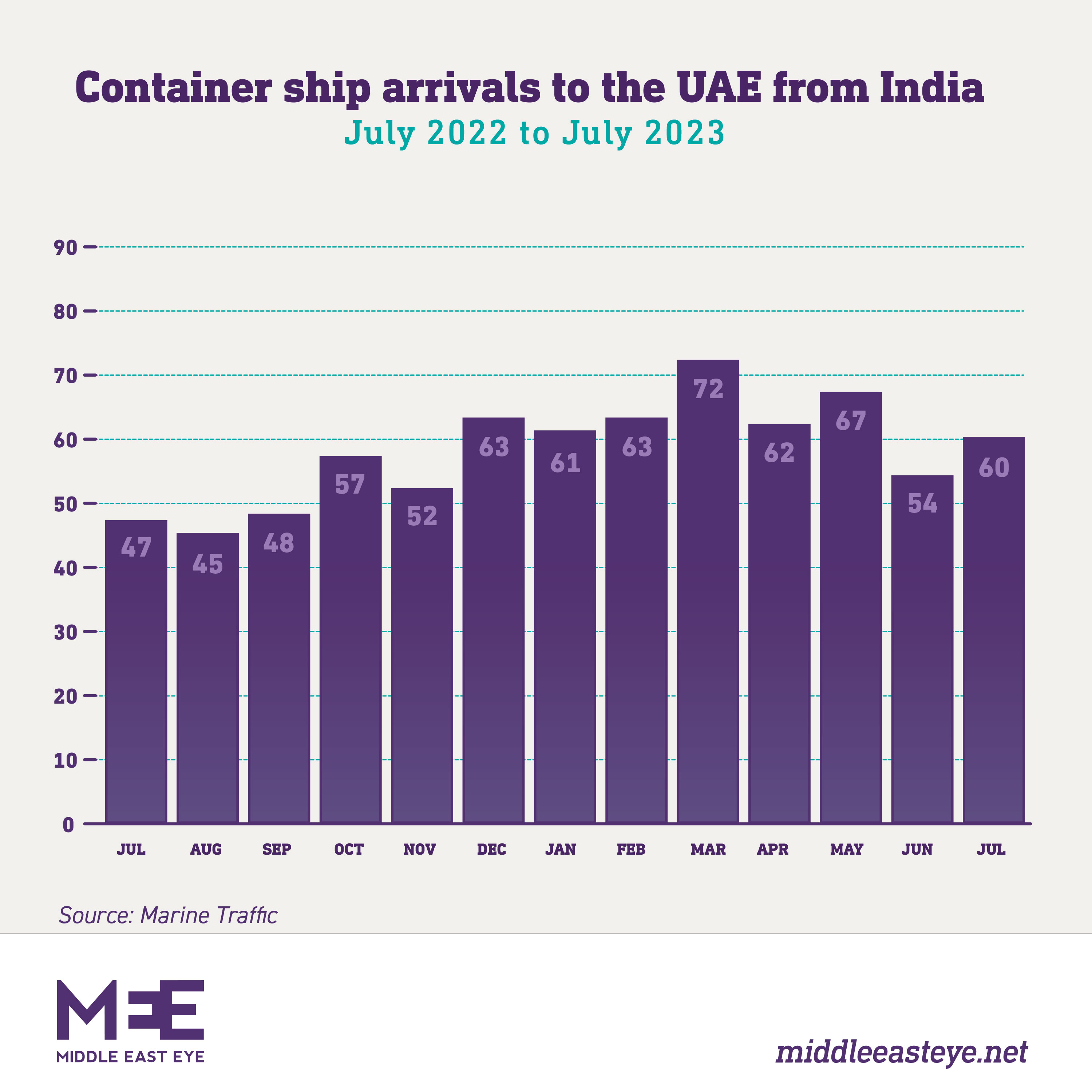

Last year, the UAE and India signed a free trade deal and have agreed to settle bilateral trade in rupees, which hit a record $84bn in March.

Sachin Chaturvedi, director general of the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), said the corridor would help facilitate new avenues for trade and investment, especially in places like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel, with whom Indian trade interests are increasing.

“At this point, trade with the UAE stands at $84bn and investment at $15bn. With Saudi Arabia, India’s imports are at $42bn and exports at $11bn; with Jordan, Indian trade stands at $3bn,” Chaturvedi said.

The $850bn Abu Dhabi Investment Authority has slated India’s Gujarat as the spot for its second overseas office. Now, Saudi Arabia’s investment ministry says it wants an India office too.

Satterfield says IMEC is a result of converging interests between the US and Gulf states over India.

“New Delhi is receiving an extraordinary level of attention in Washington because of the tensions with China,” he told MEE.

“One policy priority in the Middle East is to broaden ties between Washington’s traditional Gulf Arab partners and India beyond oil.”

Further integrating India

The UAE and India are already part of I2U2, an initiative to cooperate on clean energy and food security, which is backed by the US and includes Israel.

As of 2017, India and Israel have become “strategic partners”, collaborating on technology, military and agricultural programmes.

Earlier this year, the Indian conglomerate Adani Group acquired 70 percent of the Haifa Port in a deal that was set up to draw India into the Middle East and Europe, and help Israel integrate deeper into the Middle East and the far east.

If IMEC is realised it could boost Haifa’s role as a trading hub in the eastern Mediterranean, a strategic region where New Delhi has been making overtures.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Greece just before the G20 summit. After the trip, India was invited to join Greece, Cyprus and Israel in a partnership aimed at forging closer energy links.

All of this is music to Washington’s ears as it looks to increase India’s links to the West amid tensions with China.

Satterfield says IMEC is part of a wider vision in Washington to “de-risk” manufacturing and trade away from Beijing.

“IMEC is designed for India to be a critical supply point for the West, as opposed to China,” he told MEE.

“India has all the ingredients to make it happen: the world’s largest population, cheap labour costs and technology.”

Chaturvedi described the project as important to India, as it provided cost-effective access to all partner countries involved in IMEC.

“The details of the financial part of it are yet to come in [to the] public domain, but I think the skill, engineering and knowledge-specific inputs would certainly be there,” Chaturvedi told MEE, noting that India has also increased its capital expenditure by more than double between 2020-1 and 2023-24.

Could Egypt be a loser?

Outside the DC beltway, others are more cautious about the prospects of the IMEC.

“The IMEC corridor looks like a combination of promises, idealism and the search for a narrative,” Peter Frankopan, an expert on global trade routes at Oxford University, told MEE.

“The Middle East does, always has, and always will connect to Europe; [but] the idea of India ‘linking’ to the Mediterranean in ways that it does not already sounds more like diplomacy by PowerPoint than anything new and substantive,” said Frankopan, author of The Silk Roads: A New History of the World.

The fastest sea route today for goods transiting between Asia and Europe is the Suez Canal. About 12 percent of global trade, or about one-third of all global container traffic, passes through the 118-mile waterway.

While the canal was blocked in 2021 when a container ship ran aground, logistics experts tell MEE the 150-year-old manmade waterway has held up pretty well over the years.

‘If IMEC materialises and becomes an alternative route, Egypt could stand to lose out from the shift in trade corridors’

– Jesse Marks, Stimson Center

Some say that if IMEC gets off the ground, it could sap cargo traffic through the Suez Canal, depriving Egypt’s cash-strapped government of a major source of foreign revenue.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has bet big on infrastructure projects. The 2015 expansion of the Suez Canal was a centrepiece of his economic programme.

The canal has seen an increase in vessels and tonnage. In 2019 it registered 18,483 vessels; by the end of the 2023 fiscal year that number had jumped to 25,887.

As it grapples with sky-high inflation and a shortfall in foreign currency, Cairo has hiked transit fees through the canal. Revenue was up by about 35 percent this year, compared with last, hitting $9.4bn, a rare bright spot for Egypt’s otherwise beleaguered economy.

“If IMEC materialises and becomes an alternative route, Egypt could stand to lose out from the shift in trade corridors,” Marks, from the Stimson Center, told MEE.

About half of the tonnage that passes through the Suez Canal is from container traffic. Tankers transporting crude and fuel, along with LNG ships, account for roughly 30 percent.

IMEC ‘just another option’

As it has been proposed, IMEC isn’t designed to transport crude and fuel, Europe’s main imports from the Gulf, experts tell MEE.

“Egypt would keep getting that traffic,” Howard Shatz, a senior economist at the think tank Rand, told MEE. “My gut tells me China will not want to use this US-backed rail corridor.”

Shatz says that while Egypt’s revenue could take a hit if IMEC does materialise, it’s unlikely to spell a death knell to the Suez Canal, which would remain a cheap, reliable option for heavy bulk cargo, even if IMEC is faster.

“From a logistics point of view, IMEC’s value lies in creating more redundancy for global supply chains. New routes are definitely a good thing,” he said.

Trade between the EU and India is also growing – the bloc was the second-largest destination for Indian exports in 2021. But India’s key products are diesel and fuel, apparel items and smartphones.

For now, Shatz is sceptical that the transit corridor would make India a more attractive reshoring hub for sensitive technologies away from China.

“Chips and semiconductors are high-value, low-weight products. They tend to move by air, not railroad,” Shatz told MEE. “I don’t see the corridor alone convincing businesses to move their production to India.”

Peter Sand, chief analyst at shipping data provider Xeneta, said that if the US-backed corridor comes to fruition it would be “one extra option to pick up on; for the few, not the masses”.

It’s a big deal, says MBS

A week after IMEC was announced, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman heaped praise on the project, in his first interview with an American TV channel since 2019.

“This project will cut the time of goods from India to Europe by three to six days,” he told Fox News. “[It will] cut time, save money and it’s more safer and more efficient.

“And it’s not only about moving goods and building railways and ports. It’s about linking grids, energy grids, data cables and other stuff that will benefit Europe, the Middle East and India… It’s a big deal for us, Europe and India.”

Ties between the US and Saudi Arabia had come under strain when Biden vowed to make the prince a pariah over human rights. The two also clashed over energy policy, with Riyadh rejecting Washington’s call for it to pump more oil to tame rising prices.

But at IMEC’s G20 rollout, Biden opted for a handshake with the crown prince instead of the infamous fist-bump he gave on his visit to the kingdom last year.

‘It’s not only about moving goods and building railways and ports. It’s about linking energy grids, data cables and other stuff’

– Mohammed bin Salman

Senior White House officials are now shuttling between Riyadh and Washington to coax Saudi Arabia into normalising ties with Israel.

“This corridor gets to Europe by going through Israel,” Yoel Guzansky, a Gulf expert at the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies, and former member of Israel’s National Security Council, told MEE.

“IMEC goes hand in hand with normalisation, but even if it doesn’t happen, Israel and Saudi Arabia are still linked by rail,” he said. “And there isn’t a lot of Israeli investment required. For Israel, IMEC is all upside.”

One thing is for certain, though: Gulf funding will be crucial to the corridor’s success.

Frankopan, the author of Silk Roads, said he would be “amazed” if US tax dollars funded the project.

“As we’ve seen in recent years, ‘America first’ means bringing jobs back to the US, not helping create them in other parts of the world,” he said.

No binding financial commitments were made by the parties to the Memorandum of Understanding, but they have agreed to meet within 60 days to come up with a timetable for the project.

But the White House has said Saudi Arabia committed $20bn to support the new infrastructure plan.

Gulf states are already throwing their oil riches into infrastructure projects in a bid to reduce their economies’ reliance on fossil fuels. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi see a future as global logistics hubs complementing their newfound independence in a multipolar world.

“The world is changing,” the Emirati minister of economy, Abdulla bin Touq Al Marri, said on Friday. “We are in the business of re-engineering and redesigning supply chains.”

MBS’ slice of cake

Just last year, officials in Saudi Arabia pledged to lay 4,971 miles of new railway. Washington may be betting they won’t mind adding some extra track, analysts say.

“Being at the centre of a rail link to India and Europe kills a lot of birds with one stone for MBS and MBZ,” Robert Mogielnicki, a senior resident scholar with the Arab Gulf States Institute, told MEE, referring to the leaders of Saudi Arabia and the UAE by their initials.

Many of the components for the US-backed plan are already in place. The Emirati port of Jebel Ali has been a distribution hub for the region for decades. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are connected by some rail track. Saudi Arabia’s North-South Line runs up to the Jordanian border.

“The railroad won’t be developed from scratch,” Prem Kumar, a former adviser to President Obama and now lead for the Middle East practice of global advisory firm Albright Stonebridge Group, told MEE.

But expanding the network in Saudi Arabia could be challenging, because it has to pass through inhospitable desert terrain prone to sandstorms and scorching heat.

Saudi Arabia’s crown prince has shown he is willing to gamble the kingdom’s oil riches on mega-projects whose economic returns are far from guaranteed. He’s also constructing a $500bn futuristic mega-city along the Red Sea coast and a new downtown in the capital, Riyadh.

Mohammed bin Salman has boosted that 27 percent of world trade passes around Saudi Arabia.

“Right now, Saudi Arabia doesn’t benefit from that,” Kumar said. “This is the Saudis’ chance to grab a piece of that cake.”

The kingdom has been trying for more than a decade to expand its rail network. Analysts say more track is going to be crucial if it is serious about developing a domestic mining industry.

The government says that $1.3 trillion in metals are buried within its soil.

“Minerals will become the third pillar of the economy after oil and petrochemicals, and there is no way the mineral industry can exist without the railway,” Rumaih Al Rumaih, the kingdom’s deputy transport minister, said in 2014 when he was head of Saudi Arabia Railways.

Jordan and Israel

Haifa port is already owned by India’s Adani Group and Israeli officials estimate they only need 200 extra kilometres of track to bring a train leaving Saudi Arabia to its last terminal in Israel via Jordan.

Neither Israel nor Jordan are signatories to the IMEC memorandum of understanding.

Jordan normalised ties with Israel decades ago, but agreements with Tel Aviv often spark backlash on the street. In 2016, protests erupted in Jordan after Amman signed a deal to import Israeli gas. The deal, however, eventually went through.

Jordanian exporters, many of whom privately tell MEE they would use a railroad to Haifa, send their products on a longer route to the southern port city of Aqaba for export abroad.

But according to Kumar, who served as director for Israeli, Palestinian and Egyptian affairs at the White House National Security council, King Abdullah II, who exercises near absolute power in Jordan, would be able to push the rail-link through and ride out any backlash on the street.

“There would be enough incentives from Saudi Arabia to make this project in Jordan’s interest,” he added.

Jordan’s cash-strapped government has been trying to mend fences with Riyadh after it exposed an alleged plot to overthrow King Abdullah II that some say was backed by the Saudi crown prince.

The deal would boost Amman’s standing in the US, which is Jordan’s main foreign aid donor.

But between the skepticism of economists and the zealous policy wonks, less has been spoken of how these developments will severely impact the Palestinian quest for self-determination.

While the Abraham Accords created the political environment to forward Israeli normalisation with much of the Arab world, the I2U2 bloc and IMEC corridor have not addressed the issue of an independent Palestinian state.

Scholars like Sharri Plonski, from Queen Mary University, have likened the purchase of Haifa Port as to “offshoring of Israel” in which Palestinians are erased under the pretext of trade, securitisation and shifting supply chains.

Erdogan’s alternative

Whereas the project has yet to break ground, it has already begun riling other regional powers who see themselves as natural bridges between East and West.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said: “There can be no corridor without Turkey.”

In May, Erdogan and his Iraqi counterpart, Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ Al Sudani, unveiled their own plans for a land and railroad corridor stretching from the Iraqi province of Basra to the Turkish border, which would bring goods to Europe.

Bilgay Duman, a coordinator for Iraqi studies at the Ankara-based think tank Orsam, told MEE that Turkey is supporting Iraq’s Development Road project in a bid to improve commercial relations with the Gulf.

The Syrian civil war disrupted Turkey’s main artery to the Gulf. Because of the fighting, Turkish exports began transiting south via Israel’s Haifa port and Jordan.

“Iraq is Turkey’s gateway to the Middle East,” Duman said. “Iraq also sees that the easiest way to reach Europe is Turkey.”

Turkey says the UAE and Qatar back the proposal, but it’s unclear whether investors would support a $17bn high-speed train in Iraq given its political instability and security concerns. Baghdad’s cash-strapped government would be unlikely to finance the project, analysts say.

Leaders from Washington to Riyadh and Ankara can all pitch their versions of the 21st-century Hejaz railway. The real test for these speculative trade routes will come from the market, Frankopan says.

“Trade that is pushed top down tends not to work very well – governments of all kinds tend to be poor at making long-term commercial decisions,” he said.

“Those who make, buy and sell goods tend to be far better at joining up dots.”