September 16th, 2015

Via The Economist, an interesting article on how China’s latest wave of globalizers will enrich their country—and the world:

AN ENORMOUS MAP of the historic Silk Road hangs on a wall at Wensli, a leading Chinese silk producer. Nearby exhibits put China’s silkmaking tradition into context. The Chinese first encountered silkworms about 6,000 years ago. Two millennia later they built the first silk machine. When France emerged as Europe’s silk centre in the 16th century, it learned techniques from China, then the world’s most advanced economy.

The Chinese love invoking their country’s rich and glorious past, so they lapped up President Xi Jinping’s “One Belt, One Road” plan, announced in late 2013, which aims to restore the country’s old maritime and overland trade routes. Mr Xi hopes to lift the value of trade with more than 40 countries to $2.5 trillion within a decade, spending nearly $1 trillion of government money. SOEs and state financial institutions are being pushed to invest overseas in such areas as infrastructure and construction. According to the EIU, planners see this as an outlet for the vast overcapacity in industries such as steel and heavy equipment. It seems likely to lead to a massive spending binge, but companies should remain wary. Government support will not necessarily ensure success.

Li Jianhua, Wensli’s chief executive, is quick to praise the president’s initiative. He tweets a silk-themed message on WeChat every day in support of One Belt, One Road. Wensli, a private conglomerate with revenues approaching $1 billion, has long been close to the Communist Party. Shen Aiqin, Wensli’s founder (and Mr Li’s mother-in-law), served as a deputy to the National People’s Congress. But Mr Li is not a party member and insists that “nothing in our operations has to do with the government.” A good relationship with officials helps, he explains, if only so he can refuse when they press him to invest in “strategic” industries: “This happens a lot…but I say no, we are a silk firm.”

Wensli is reviving the Sino-French silk connection, but on its own initiative. Two years ago the company acquired Marc Rozier, an old-established French silk firm. Mr Li says he bought it to find out how the French make the world’s best luxury goods. Wensli’s supply-chain expertise and cash are helping Marc Rozier expand. In turn, the French firm is helping its Chinese owner improve quality and develop a global brand.

Robots and teapots

Many more Chinese firms like Wensli are venturing abroad. Ninebot, a transport-robotics startup backed by Xiaomi and Sequoia Capital, bought Segway of the United States (and its IP) in April. Segway’s products are too pricey and heavy for the mass market; Ninebot has the supply-chain and engineering expertise to change that. Sequoia’s Neil Shen says that “today it’s not just copycats…China will expand, through its own innovations and through acquisitions.”

Chinese firms are also trying to revive old traditions of craftsmanship, which may help them develop authentic brands. Jiang Qiong Er says she founded Shang Xia, with help from Hermès, a French luxury-goods maker, out of a burning desire to prove that it is possible to create a “Chinese brand of excellence”. The firm’s flagship store is on Huai Hai Road, Shanghai’s most elegant shopping promenade. Her luxury boutiques design, make and sell hand-crafted tea sets, jewellery, clothes and furniture from local materials such as bamboo and silk. She has opened a shop in Paris and hopes in time to become a global brand.

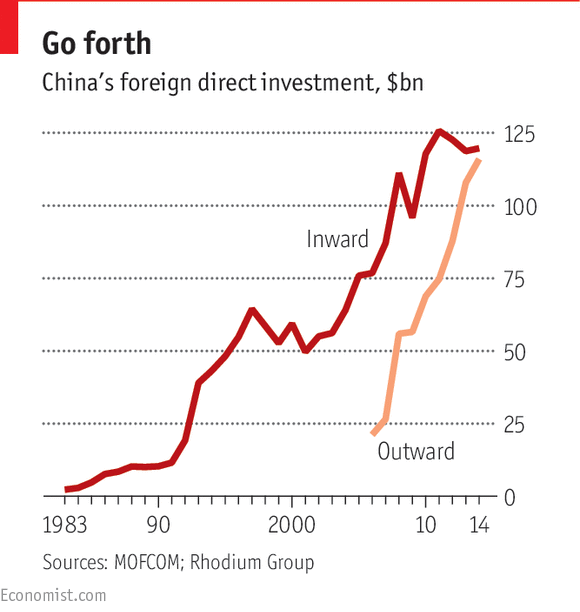

Last year Chinese investment overseas almost caught up with foreign direct investment in China (see chart). According to the China Global Investment Tracker, a research service, Chinese investment abroad in the first half of this year amounted to $56 billion, a rise of 14% on a year earlier. Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute, two other research firms, reckon that the total stock of Chinese direct investment abroad could rise to $2 trillion by 2020, from less than $800 billion at the end of 2014.

Not everyone will be pleased by that prospect, remembering an earlier wave of Chinese globalisation led by SOEs. They made clumsy forays, and enemies, in such places as Africa and Latin America on a quest for oil, agricultural land and other resources. Many deals were politicised and some were corrupt. The resulting backlash was understandable but overdone. In particular, the decision in 2012 by a committee of America’s Congress to blacklist Huawei and ZTE, another big Chinese telecoms firm, on national-security grounds was shameless techno-nationalism. It has given Chinese officials cover for their own misguided attempts to favour firms like Lenovo and Huawei at the expense of IBM, Cisco and other American technology firms.

Fortunately, future Chinese would-be investors abroad are more likely to be market-minded entrepreneurs than national champions. Chinese firms are getting fed up with paying licensing fees and royalties to foreigners. So instead of renting or stealing intellectual property, says Harvard’s William Kirby, they are looking abroad to acquire top talent and technologies. And despite Huawei’s troubles, their favourite target is America.

Earlier Chinese attempts to capture foreign markets and technologies did not go well. In 2004 Shanghai Automotive acquired 49% of SsangYong, a South Korean carmaker, for $500m, hoping that the acquisition would help it enter the American market, but cultural clashes, union troubles and rising oil prices got in the way. In 2009 SsangYong went bust and Shanghai Automotive had to write it off. TCL, a big electronics firm in Guangdong province, bought majority control of the television arm of France’s Thomson in 2004, giving it the Thomson and RCA brands. But TCL’s inexperience and the technological disruption caused by flat-screen technology scuppered the effort, and the venture was shut down.

These examples highlight some of the problems Chinese firms face when going overseas, and explain why many have failed. Chinese firms have few managers with international experience. Their brands and management processes tend to be poorly developed. They are also reluctant to pay outside experts for advice even when they desperately need it.

But Chinese firms are getting better. A study by Claudio Cozza and colleagues published last year by the Bank of Finland looked at Chinese investments in the EU, which went from almost nothing in 2004 to €14 billion ($18 billion) in 2014. They chose Europe because Chinese firms tend to look for new markets and to acquire brands, technologies and knowledge there. Such outbound Chinese investments in the EU, they found, had “a positive effect on [Chinese] firms’ efficiency and performance” and pushed up their overall sales.

Some Chinese firms are already veterans of globalisation. Huawei’s intrepid staff have long been selling telecoms equipment in remote parts of Africa and Latin America. One executive recalls that in the period following America’s invasion of Iraq the only foreigners granted safe passage by all sides were Huawei’s Chinese engineers, who were repairing vital communications infrastructure. Another example is Lenovo, which unusually for a Chinese firm has many nationalities on its senior management. In 2005 it bought IBM’s personal-computer business, and last year it took over Motorola’s handset business (from Google) and IBM’s low-end server division. Haier has acquired part of Sanyo Electric’s home appliances division and Fisher & Paykal of New Zealand in recent years and is now the world’s biggest white-goods maker.

That is only the beginning. In “China’s Disruptors”, Edward Tse argues that “China’s entrepreneurial companies will become far more active internationally, entering new markets, acquiring companies and hiring executives.” He believes they will pose an enormous threat to established businesses in many industries. And yet global Chinese entrepreneurs could also be good for the world, as Wanxiang’s example shows.

“A country that cannot support entrepreneurship has no hope,” says Lu Guanqiu, the septuagenarian boss of Wanxiang, once a humble township-and-village enterprise in Zhejiang province but now one of the world’s biggest independent car-parts firms. Township-and-village enterprises were left out of state plans and denied access to raw materials and to the official distribution system. In the early hardscrabble days, Mr Lu collected spent artillery shells and made them into ploughs to sell to farmers. These days Wanxiang’s sales top $20 billion a year, of which over $3 billion are made in America, where the firm sells components to the big three carmakers in Detroit. It has also bought two dozen companies in America.

Take a deep breath

A sexy electric roadster is parked outside A123 Systems, a battery firm in Michigan. It is made by Fisker Automotive, a failed American firm acquired by Wanxiang, and it is meant to inspire. Jason Forcier, A123’s boss, says his firm would not be there except for Mr Lu’s dream about solving China’s pollution problem. Wanxiang bought the company at a bankruptcy auction in 2012 for about $250m and imposed strategic focus and cost discipline on the free-spending startup. Mr Forcier expects a profit this year.

Wanxiang has come to America to learn how to make China, and maybe the world, a cleaner place to live in. It has built a solar plant outside Chicago and invested in coal-to-natural-gas technology in Massachusetts. Back in China, it is accumulating the in-house expertise and alliances needed to make affordable electric vehicles for the mass market.

Mr Lu’s quest is not as Quixotic as it seems. China is the world’s best place to scale up clean technologies, wherever they are invented. His effort is just a tiny fraction of the $2.5 trillion that the UN expects to be invested in clean energy in China by 2030. In future, says the green billionaire, Chinese firms “will contribute more merit and value to the world”.

China’s best firms are standing ready to go global. As Thomas Hout and David Michael write in a recent issue of the Harvard Business Review: “If there’s a business equivalent to the Cambrian period of explosion and extinction of species, China from 1991 to the present is it.” Many have failed, but the survivors are straining at the leash.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.