A partial solution to Europe’s energy crisis can be found off the coast of Israel, roughly a mile beneath the surface of the Mediterranean Sea. Now they just need a cheaper way to transport it.

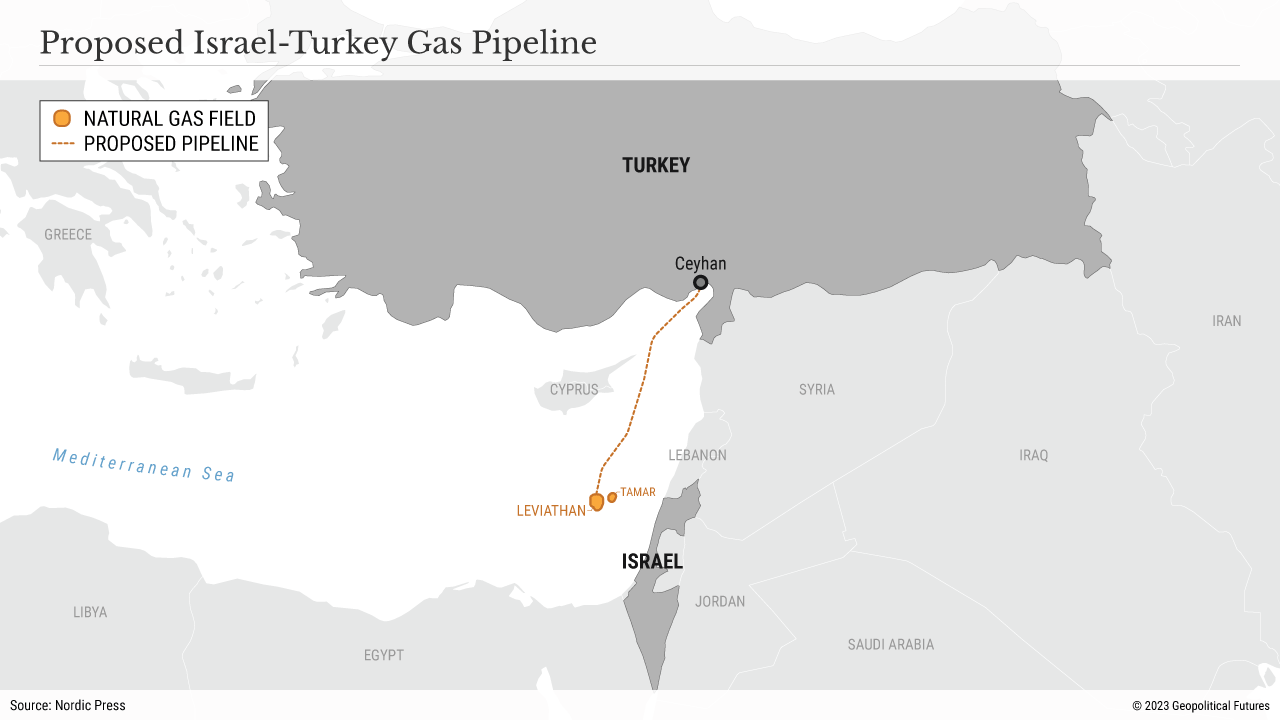

For more than a year, Turkish and Israeli officials have shuffled between each other’s capitals, hinting at a potential energy corridor linking the Leviathan offshore gas field to Europe. Plans for a pipeline have been around for years but were re-energized in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as the European Union sought to replace the 40 percent of its gas supplies that came from Russia. But while it would be much cheaper than rival projects (such as the EastMed pipeline), regional politics, unpredictable market demand and emerging alternatives mean the Turkish-backed pipeline is unlikely to be built.

Investors, industrialists and government officials have been working up proposals to move natural gas from Israel’s Leviathan field to consumers in Europe since the field’s discovery more than a decade ago. A previous plan, the EastMed pipeline, broke down over its hefty $6 billion price tag, sharp criticism from Turkey over its exclusion, and finally the Biden administration’s January 2022 decision to withdraw U.S. support. A short time later, Ankara pitched its much cheaper alternative: a $1.5 billion, 500-kilometer (310-mile) route from Leviathan to Turkey, which dreams of becoming a regional gas hub.The first challenge was that Israel and Turkey were hardly on speaking terms. The regional rivals have deep-seated differences over energy exploration in the Mediterranean, the Cyprus conflict and the Israeli-Palestinian issue. In February 2022, a high-level Turkish delegation visited Israel to break the ice, framing energy cooperation as key to further political, economic and security collaboration after years of strained relations. The following month, Israel’s president trekked to Ankara – the first state visit to Turkey by a high-ranking Israeli official in a decade – where the pipeline was discussed. Turkey’s foreign minister traveled to Jerusalem in May to continue the conversation, and by August the two sides had agreed to restore diplomatic relations.

Both sides gave ground to reach this point. When Israeli security forces clashed with Palestinian protesters at the Al-Aqsa Mosque last spring, the Turkish government refrained from criticism – something that would have been unthinkable not long ago. Similarly, Israel went quiet on the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, the regional bloc that pushed the EastMed pipeline, indicating greater interest in alternative energy projects. Amid intensifying great-power competition, it is in both countries’ interest to patch things up with old foes for the benefit of foreign policy flexibility.

However, a subsea pipeline through multiple countries’ exclusive economic zones is still a major undertaking. Facing uncertain demand dynamics, intricate regional politics and new challengers, the Israeli-Turkish pipeline is likely dead in the water.

First, the pipeline would cross Cyprus’ EEZ, touching on a sore spot for Mediterranean stakeholders. Since 1974, the island of Cyprus has been split between a Greek Cypriot south and a Turkish-occupied north. The Turkish government does not recognize the Greek Cypriot government, whose approval would be required before starting construction within its EEZ. Additionally, the main backer of the Greek Cypriot government, Greece, has its own ambitions to become a bigger transit state for gas to Europe and would not want to see its rivals in Turkey strengthened. Greece, Cyprus and Israel are all members of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, and they frequently conduct military exercises together, so it is unlikely that Israel would proceed with the pipeline project without their support.

Similar issues could arise with Syria, whose EEZ the pipeline would also likely traverse. After Iran, Israel considers Syria to be one of its greatest regional foes. In addition to decades of bad blood and territorial disputes, the Assad government has recently unnerved the Israelis by staging Iran-aligned militias and Hezbollah fighters along their shared border. Turkey flirted with normalizing relations with the Assad regime, particularly after the February 2023 earthquake that devastated northern Syria and southern Turkey, but it held back because of disagreements over the status of northwest Syria and the repatriation of Syrian refugees, among other things. Trying to gain Syria’s consent for a pipeline through its EEZ would be fraught for Turkey, but for Israel it’s a nonstarter.

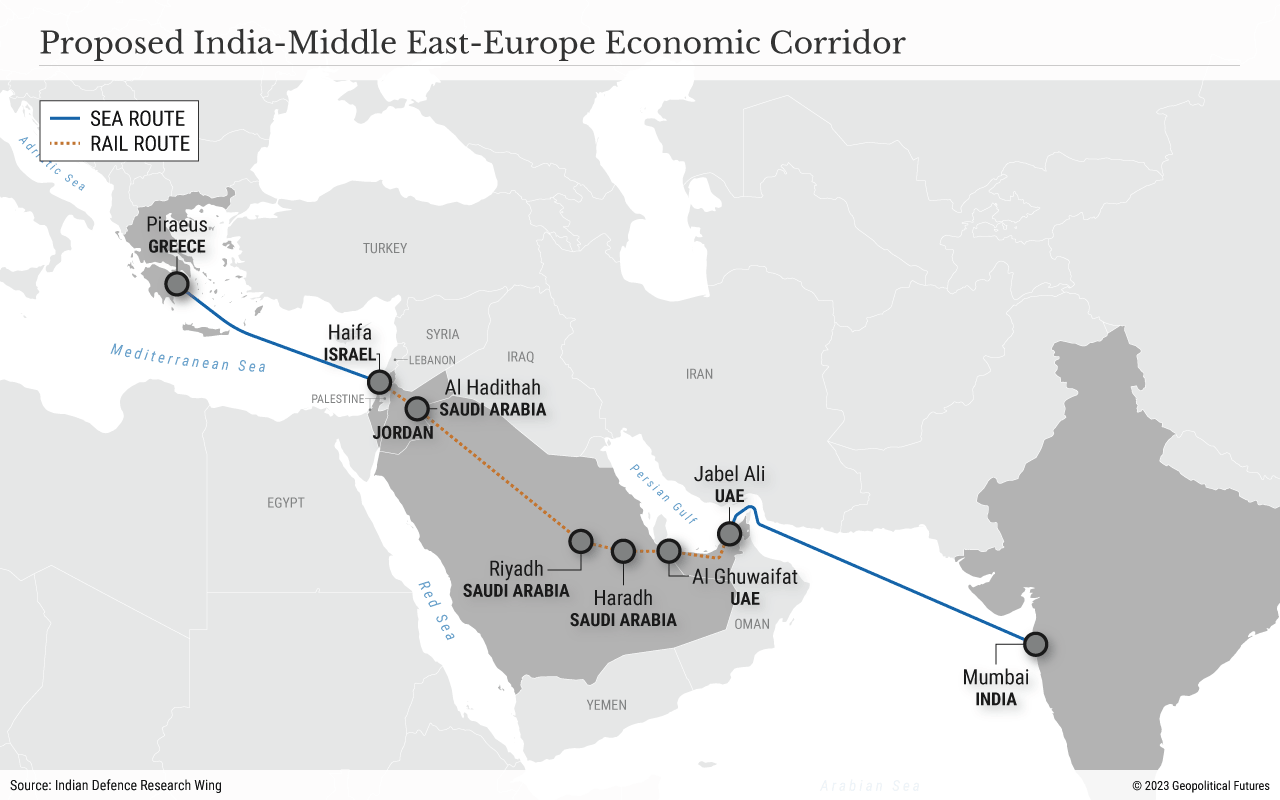

Finally, an alternative project may be taking shape in the form of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, which includes Israel but not Turkey. Consisting of railways, ports, electricity and data links, and even infrastructure to make and ship green hydrogen, the IMEC is a formidable rival. It also enjoys the support of India, the U.S., the EU and the Arab Gulf states. Although Israel did not sign the memorandum of understanding outlining plans for the IMEC, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu voiced support for the deal, indicating potential interest not only in participating in the corridor but also in using it to build on normalization efforts with the Arab Gulf states. Such a gargantuan undertaking will be hard to get off the ground, but if it includes Israel, it would make plans for a pipeline with Turkey redundant.

An Israeli-Turkish energy corridor to Europe makes sense on paper. It would satisfy Europe’s need for alternative gas suppliers, Turkey’s quest to become an energy hub and Israeli efforts to improve and diversify relations in the Middle East. However, given the issues with Cyprus and Syria, not to mention the IMEC proposal, Turkey will probably soon be its lone proponent.

The Turkish-Israeli Gas Pipeline Is Dead in the Water

September 15th, 2023

September 15th, 2023

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at how regional disputes and rival plans could deal another blow to Turkey’s dream of becoming an energy hub:

This entry was posted on Friday, September 15th, 2023 at 6:20 am and is filed under Turkey. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.