We live in an age of interregional connections. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, after a decade and hundreds of billions of dollars in spending, has faced significant setbacks but remains the most prominent example. Attempts to develop the Trans-Caspian International Trade Route, also known as the Middle Corridor, have gained momentum since Russia invaded Ukraine, spurring other countries to seek ways to bypass Russian territory for east-west commerce and to reduce dependency on Russian hydrocarbons. The latest connectivity corridor emerged last weekend at the G20 summit, during which the United States, India, Saudi Arabia and others signed a memorandum of understanding to establish a network of maritime and rail routes connecting the Indian subcontinent with Europe via the Middle East.

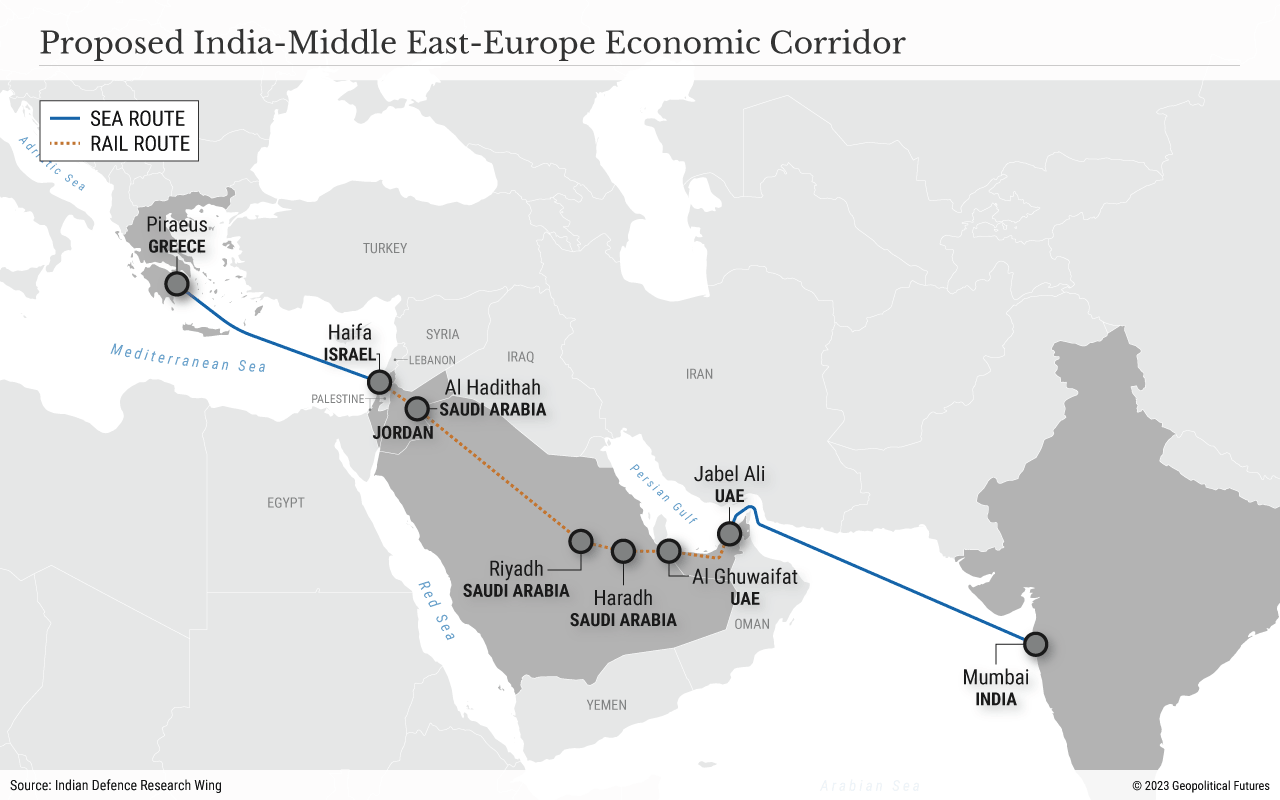

Details are scarce, but the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor will consist of rail lines and seaports linking India and Europe across the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel. In addition to reducing transit times for goods, the IMEC project is expected to include infrastructure for the production and transport of green hydrogen and an undersea cable to enhance telecommunications and data transfers. The most interesting aspect of the corridor came from the U.S. deputy national security adviser, who said it was not just an infrastructure project but was informed by a U.S. strategy of “turning the temperature down” in the Middle East, which historically has been a “net exporter of turbulence and insecurity.”

It appears the United States’ growing alignment with India is enabling Washington to stitch together four key landmasses – Europe, the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia – from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This resembles the British strategy during that empire’s heyday, when England saw the Middle East as a critical junction between it and its colonial possession of India. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Arab world remained a strategic challenge for the United Kingdom. It is all the more so for the United States in the 21st century. As the most unstable element of the planned corridor, the Middle East will be the focal point.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that the envisioned corridor bypasses the major hot spots of the region, such as Yemen, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, which together comprise Iran’s sphere of influence. Additionally, the Levant, though a key piece of geopolitical real estate between the Arabian Peninsula and the European continent, is in disarray, especially after the Syrian civil war. This would also explain why Turkey, which is the landbridge between the Middle East and Europe, is not part of the corridor. Egypt is the other major exclusion, likely due to its economic problems, which are worsening despite several billions of dollars of financial assistance from the energy-rich Gulf Arab states just in the past 10 years of President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi’s rule.

The core component of the IMEC is Saudi Arabia, which under Mohammed bin Salman is experiencing a social and economic revolution. The crown prince’s ambitious Vision 2030 roadmap seeks to transform the country from a religiously ultraconservative kingdom heavily reliant on crude oil exports into a modern country with a diversified economy that is deeply integrated with the rest of the world. Saudi Arabia (together with the UAE) has increasingly close geoeconomic ties with India. Therefore, this project is very much in keeping with Riyadh’s imperatives.

However, the newly announced corridor has a major chokepoint: Jordan. Bordering Iraq, Syria and the Palestinian territory of the West Bank, the small Hashemite kingdom occupies a highly unstable strategic environment. Jordan’s infrastructure will also need serious upgrading, especially considering the country’s weak economy, which has been burdened by hosting more than a million Syrian refugees. But perhaps the most significant factor is the country’s proximity to the West Bank, where the meltdown of the Palestinian Authority and the growing number of Jewish settlements has created a precarious situation.

The corridor project also comes as the Biden administration has been pushing Saudi Arabia and Israel to establish formal ties. Washington and Riyadh have already agreed on the broad parameters of such a deal. It is in the Saudis’ interest to normalize relations with the Israelis, but they cannot do so at the cost of disregarding the Palestinian issue. In the past two weeks alone the Palestinian Authority has signaled that it is willing to settle for modest territorial concessions from Israel vis-a-vis the West Bank. Meanwhile, the Saudis are engaging the Palestinians over financial assistance.

Integrating the West Bank into the project would be a way for the Saudis to forge relations with Israel while also developing the corridor. The Palestinian territory sits between the Jordanian capital of Amman and the Israeli port city of Haifa, whence the second maritime segment of the corridor begins the journey through the Mediterranean to Eastern Europe. Of course, this would be a massive undertaking and would depend on an unlikely level of relative peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians in the West Bank. Even if the route bypasses the West Bank, growing political instability and polarization within Israel is its own risk.

As if all these Middle Eastern factors were not enough of an impediment, the European stretch of the corridor through the Western Balkans entails its own insecurity. The closest European destination from Israel is Greece, and to get to the wider continent the route goes through the Balkans.

Considering all the issues that would need to be addressed, the IMEC project will struggle to become a significant economic connectivity channel. For now, the corridor will likely be limited to the maritime route connecting India to the Gulf Arab states – a route that is still in many ways commercially vibrant.

The Viability of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor

September 13th, 2023

September 13th, 2023

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at the the India-Middle East-Europe economic corridor, an ambitious new connectivity project will likely run aground in the Arabian Peninsula:

This entry was posted on Wednesday, September 13th, 2023 at 5:24 am and is filed under India, Saudi Arabia, UAE. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.