May 18th, 2023

Courtesy of Geopolitical Futures, analysis of China’s new approach in Africa:

China is moving away from its landmark Belt and Road Initiative in favor of smaller direct investments in strategic projects like renewable power and communications. In 2013, Beijing unveiled the Belt and Road, consisting of huge loans for gargantuan infrastructure projects in the Global South. Africa was a major recipient of these loans. However, many BRI projects have not been completed or have been hamstrung by ballooning budgets, failure to repay debts or poor workmanship overseen by Chinese engineers. These disappointments are leading Beijing to reassess its strategy toward Africa.

Resource Security and Political Capital

China’s endgame in Africa is to create favorable trade relationships and a reliable pipeline of natural resources. The strategy behind BRI was to exchange investment for political capital. China would help its partners develop transit routes to promote trade, both within the continent and with the outside world. For Beijing, warm relations with BRI recipients would ensure supply chain security and cheap mineral extraction with reduced royalty payments. At the time, China was also concerned about the security of its oil supply. Improved relations would also support Africa’s imports of Chinese goods; in 2009, China surpassed the U.S. as the top trading partner for Africa, and today it trails only the EU.

Generally, Chinese capital has flowed to Africa in two forms: foreign direct investment or loans from the government, commercial banks or state-owned banks. Over the past few years, however, Beijing has poured less capital into things like transportation infrastructure, hydrocarbon pipelines and massive power projects. Instead, it is focused on buying equity in mining projects, funding smaller power-generation projects (especially renewable power), building internet and communications networks, and modernizing African government facilities. Renewable power projects are often profitable in the short term and generate goodwill with ruling parties, as do investments in government buildings.

One thing China has found is that it can access the continent’s critical minerals, oil and gas without the huge investments that it once thought were key. Of the $169 billion that Chinese development banks and the government have lent to Africa, for example, a quarter went to Angola to be invested in its state-run oil company in a bid to ensure China’s own oil supply. Today, 25 percent of China’s oil and gas comes from Africa, behind only the Middle East. Through long-term supply contracts and favorable political conditions, China has avoided its immediate supply security fears. The same has been true of critical minerals like lithium, copper and cobalt. In the past, Beijing overinvested in resource-rich countries and used the minerals as collateral. In fact, African politicians were grateful for the Chinese investment and the often-favorable partnership terms with Chinese mining companies.

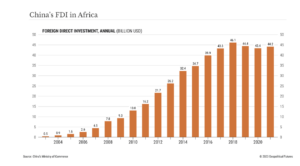

Chinese lending ramped up through the 2010s and peaked in 2016. From 2012 to 2018, when China stopped funding many of these projects, its Africa loans totaled $107.9 billion – a huge burden on China’s coffers. The massive scale of BRI lending globally brought China’s current account balance down to just $24 billion in 2018 from $293 billion in 2015, before rebounding after large external loans were drastically reduced. In 2020, China issued only $1.8 billion in loans – a massive drop. This slide looks set to continue.

Financial and Political Problems

China’s initial investment model ran into multiple problems. Financially, China has had trouble recouping much of the bilateral debt, and contrary to debt-trap fears, it has generally been accommodating when it comes to debt relief and deferred payments for emerging economies. Leniency is in China’s interest, as its African counterparts are major trading partners sitting on minerals that China processes into high-value goods.

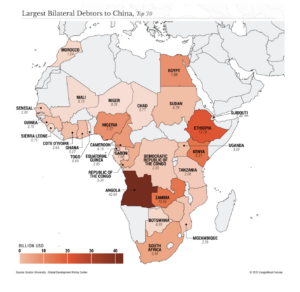

Largest Bilateral Debtors to China

Of its major loan recipients in Africa, Zambia has defaulted on repayments; Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya and Egypt are at high risk of default; and additional requests for debt relief are highly likely. Each of these countries has more than 30 percent of government revenue going toward interest payments on debt through 2023.

Politically, Beijing is faced with a choice between further debt reduction, which would keep the pressure on its own financial situation, or refusing the requests and jeopardizing the goodwill it has accrued. In addition, other creditors such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank would condemn Beijing’s intransigence. China is choosing the former. In March, Ghana’s finance minister visited Beijing to negotiate debt restructuring. Zambia has been negotiating with China and other creditors for three years on debt restructuring, a write-down on outstanding balances and reduced interest rates. The G-7 and U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen have accused China of dragging its feet on relief for highly indebted countries.

Moreover, some countries are questioning the value of Chinese loans and development finance that was earmarked for large infrastructure projects. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo recently announced that it will reassess its mining concessions with Beijing. It believes the terms may be too skewed in China’s favor. Similarly, Nigeria has concerns about the sustainability of previously incurred debt to Beijing. By mid-2022, Nigeria’s debt owed to China accounted for 84 percent of its total $4.9 billion in bilateral debt. A large proportion of Nigeria’s government revenue is going toward debt servicing, and it has been attempting to negotiate lower interest rates, believing China’s rates are exploitative.

Finally, from China’s perspective, BRI loans are unnecessary for securing access to African natural resources. China has already established itself within the African market. One example is Zimbabwe, where China has secured significant lithium mining rights without huge infrastructure projects. Even as Zimbabwe has nationalized processing and refining, China has defended its position; the only companies with lithium refineries in Zimbabwe are Chinese-owned.

New Strategy

With this in mind, China has moved away from financing massive infrastructure projects in favor of smaller ventures. Earlier this year, Uganda canceled a contract worth $2.2 billion with China Harbour Engineering Co. to build a 273-kilometer section of a standard gauge railway, citing delays in China’s financing. Kenya is also seeking funding to build its own line of the railway, but it received just $12.7 million from China this year for the project. Likewise, Nigeria has been seeking $22.8 billion for a new Kaduna-Kano railway. In 2016, China’s Exim Bank signed an agreement to fund the project. The Nigerian parliament approved the deal in 2020, but the bank pulled out in 2022. Last month, the Nigerian government announced that the China Development Bank would provide a significantly lower sum, $973 million, to finance the railway.

Beijing is now looking for less risky projects in which to direct its investments. For example, reports indicate that China could finance the East African Crude Oil Pipeline from Uganda to a port in Tanzania, after Standard Chartered Bank withdrew due to environmental concerns. The project, administered by French energy giant TotalEnergies, is considered relatively low risk. China will be a major destination for the oil once the pipeline is operational, and Chinese companies have taken over from European firms to construct multiple segments of the pipeline.

China’s FDI in Africa

Meanwhile, despite the declining appetite for large loans, China’s foreign direct investment in Africa is steadily rising. Chinese FDI in Africa increased to $44.2 billion in 2021 from $491 million in 2003 and has remained steady over the past five years, even during the COVID-19 pandemic. Its investments are focused on a small group of industries. In 2021, mining accounted for 22.6 percent ($9.9 billion) of Chinese FDI across Africa, while the construction sector accounted for 37 percent ($16.3 billion) and manufacturing for 13.4 percent. Chinese construction companies are still operating in Africa but are no longer working on government contracts paid for by BRI loans. China remains the continent’s single largest trade partner, accounting for 22 percent of Africa’s trade in 2021.

Smaller infrastructure projects are seen as long-term investments and are not funded through development loans. Many are small-scale green energy projects, including hydropower and solar and wind farms. For example, a Namibian-Chinese joint venture signed a deal worth $100 million to develop a 50-megawatt wind power plant. Such initiatives are seen as more sustainable and ultimately more profitable than the massive hydro and coal-fired power stations that previously attracted Chinese funding.

China-Built African Parliament Buildings

Chinese investments in Africa have also been directed at the seats of power on the continent. Beijing has been involved in constructing or refurbishing parliament buildings in 10 countries and other official facilities in five countries across Africa, including the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa. These projects serve as subtle reminders to the political establishment of China’s continued engagement here. Though Beijing is shifting its focus on the continent, it’s clearly not leaving it.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.