December 16th, 2024

Via Middle East – Told Slant substack, interesting analysis of Somaliland in light of the recent Turkish-brokered agreement between Somalia and Ethiopia:

Somaliland Seen Critical to Containing Iranian, Chinese Expansion in the Red Sea

Starting in 2000, with an infrastructure investment effort launched by the United Arab Emirates and its ports management company Dubai Ports World (DPW), Djibouti revived an older export route from the Ethiopian capital of Addis Abeba to to profit from Ethiopia’s diverted traffic.

But after illegally nationalizing Dubai’s shares in the ultra-modern Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) in 2018, then swapping DPW’s management for the Chinese, Djibouti has become base for a host of other regional and international powers, and from Addis’ perspective, has become insufficiently responsive to Ethiopia’s needs.

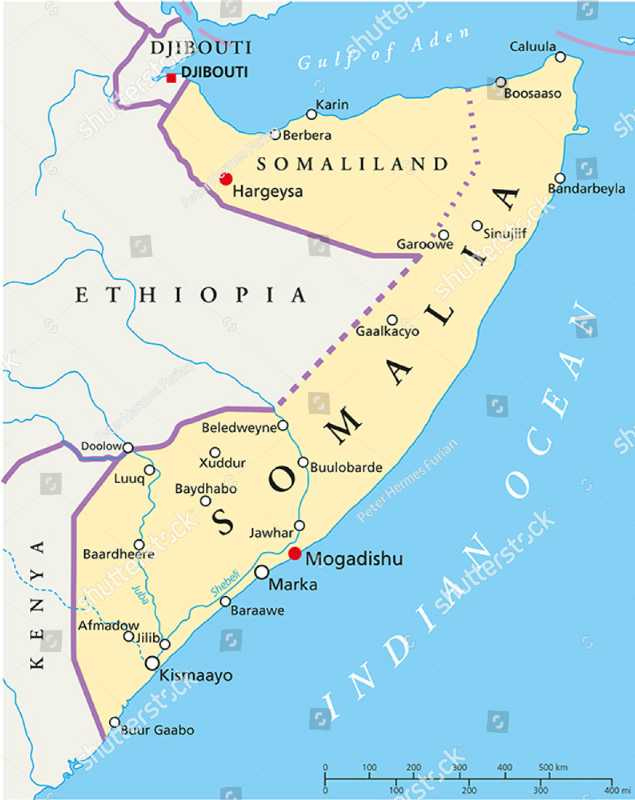

For Ethiopia, the next best options lie on the Northern Somali coast, either at or in the vicinity of the ports of Berbera (Somaliland) and Bosaso (Puntland), both of which have received Emirati investment, as the UAE tries to crowd out its former protege, Djibouti.

Ethiopia’s President Abiy Ahmed — who won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize for ending the conflict with Eritrea, but then started the so-called “Tigray” war in his own country— sees it as Ethiopia’s sovereign right to carry on its economic affairs and project its regional power in the Red Sea through a permanent navy and home port — despite not having a coastline.

These are not only military and economic needs but are unifying themes for a government and country that has been wracked by ethnic and political divisions that killed more than 600,000 people between 2020-2022 (the “Tigray War”).

Last week’s Turkish deal is about as vague as the deal it was meant to amend. It seems to suggest that Ethiopia will drop its recognition of Somaliland and work out Ethiopian access to the Red Sea with Mogadishu, rather than Hargeisa. This diplomatic flutter comes in the midst of a period of intense regional upheaval.

Putting A Good Face on Things?

Turkey had been making progress in creating pockets of influence in the Red Sea, before the Sudanese civil war started in 2023: Since 2011, Turkey had been supporting the Somali military in Mogadishu with extensive training and equipment, against the Al Qaeda-linked Al Shabab — while it sold Turkish-made drones to Ethiopia.

Turkish President Erdogan had also managed to convince former Sudanese dictator Omar al Bashir to grant Turkey a 99-year lease to develop a tourist hub in the long-neglected port city of Suakin, while Turkey’s ally Qatar negotiated a $4 billion deal to develop and manage the port itself.

This move alarmed,the UAE, Saudi Arabia — and Egypt — all of which are deeply suspicious of Erdogan’s self proclaimed “Neo-Ottoman” expansionism in the Red Sea.

Turkish-Egyptian relations had been poor since Egyptian President Abdelfattah Sisi came to power in 2014, due primarily to Erdogan’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood and Sisi’s predecessor Mohammed Morsi, but have improved in recent years.

Al Bashir’s overthrow in 2019 led to the cancellation of both the Turkish and Qatari concessions, but in any case, due to current hostilities no one is going to be getting much use out of Suakin anytime soon. There’s a real danger the country-wide fighting between Al-Bashir’s former auxiliary Rapid Supply Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Army will overflow Sudan’s borders.

Egypt’s Primal Fear: Interruption of the Nile

Egypt’s primary international concern is not Turkish expansion in Sudan, but what it considers the existential threat to Egypt’s water supply and economy posed by the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia begun construction of the dam while Egypt was distracted with the 2011 Revolution. In that context, last summer Egypt made a show of sending troops to augment Somalia’s forces — whose optics were linked to Mogadishu’s face-off with Ethiopia over the future of Somaliland.

Egypt no doubt welcomes support from any power capable of undermining its nemesis, Ethiopia. But playing this card too deeply may be a losing proposition for Turkey, given its commercial interests also require stability in Somalia, which in turn requires at least tepid relations with Ethiopia.

The Turks have seen Somalia as an anchor for strategic influence in the Red Sea region, and a means to secure access to oil and gas reserves off the Somali coast. But the probability of Turkey being able to expand its influence significantly by relying on a de facto failed state, in an already highly contested region, seems low.

Even More Convincing: A Trump Push for Hargeisa

Since its declaration of autonomy in 1991, Somaliland has stood out as a beacon of order – a small, self-governing state that has kept extremists at bay, held elections, even as it was part of a failed state — Somalia, and adjacent to another self-declared state, Puntland, the epicenter of a wave of Red Sea piracy that peaked from 2008-2012, and caused sustained distruption to Red Sea traffic.

Incoming administration officials advocate for a change in the Biden-era “United Somalia” policy in favor of independence for Somaliland and a relationship that enables the US to monitor activity in the lower Red Sea, push back against Chinese expansionism and hostile action by Iran and its Houthi clients in Yemen, and the Al-Qaeda affiliated Al Shabab in Somalia — all of which is far more than the current government in Mogadishu can can offer. In the end, United States’ recognition of Somaliland will likely to far more for Hargeisa than any promise from Ethiopia.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.