Following the conclusion of the 2023 BRICS meeting held in Johannesburg, South Africa, the official summit declaration announced that in January 2024 the BRICS group of emerging market economies would undertake in the words of the Chinese President an ‘historic’ expansion and admit five new member countries: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Argentina was also invited to join, but it’s new President Javier Milei declined the offer). While the term BRIC first came to fruition via the work of Jim O’Neill in 2001 the official creation and formalization of the BRIC bloc by its four founding members: Brazil, Russia, India and China, did not take place until 2009, followed by the admission of South Africa in 2010. As a group of high growth emerging economies, even before its recent expansion, the group accounted for 26% of global GDP and 40.8% of the global population. However, as important as the BRICS countries are economically, by their own admission the BRICS grouping is more than an economic forum, in that they commit themselves to the creation of a “more representative, fairer international order, a reinvigorated and reformed multilateral system.” Exactly what representative, fairer, and reformed translates as for the BRICS grouping is unclear, but it is often interpreted to mean that the BRICS will act as a counterweight or indeed a means to ultimately supersede Western dominance economically and politically. It is important, therefore, to reflect upon the recent expansion of the BRICS group and the implications and likely challenges for future global governance, economics, and geopolitics given the BRICS grouping is likely to expand its membership further in the years ahead.

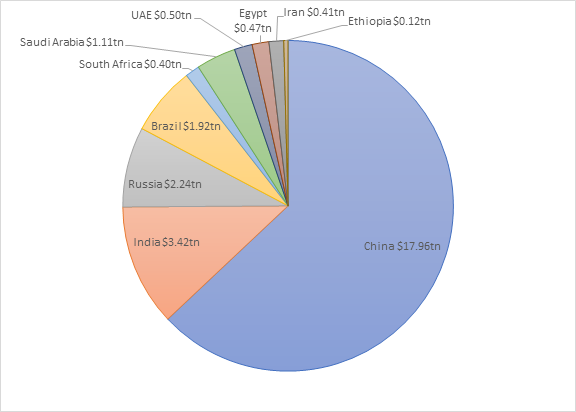

From an economic perspective the new membership will generate an additional $2.6 trillion in GDP terms representing an overall BRICS economy of $28.5 trillion and 28.1% of global output. Yet, while a significant economic grouping, by comparison G7 countries continue to dominate global output, accounting for 43.2% of global GDP.

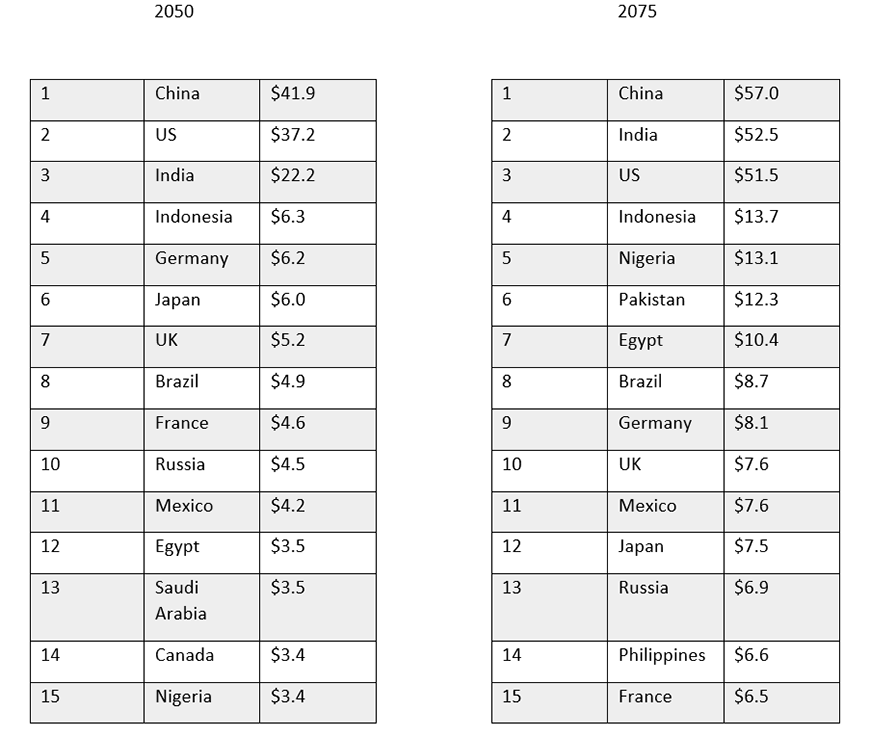

However, if forecasts are correct the size and therefore importance of the G7 economies will reduce over the coming decades, while many of the BRICS economies are projected to grow significantly. This is particularly the case in relation to new members such as Egypt and Ethiopia who are projected to grow by 635% and 1,170% respectively in GDP terms by 2050.

The projected top economies in the world for GDP (USD trillions) in 2050 and 2075:

Source: Goldman Sachs

From a trading perspective the expanded group accounts for more than 43% of global oil production, doubling its capacity, and enhancing its geostrategic reach into the Middle East via the admission of Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE. Further still, the expanded group now accounts for 25% of global exports, while the original four BRIC members account for and control 72.5% of global reserves of rare earth minerals, with China alone producing 85% of all globally refined earths in 2020. Critical for the production of a huge range of products from high-tech weaponry, but also every day consumables including electric cars, circuit boards, semiconductors, and mobile phones, rare earths face huge demand, as part of the global supply chain for products that are consumed by the rapidly expanding global middle class – of which China, India, Brazil, and Egypt alone will account for 59% of all new middle classes in 2024. Ultimately the newly enlarged BRICS grouping, which now accounts for 45% of the world’s population, will continue to grow in economic and geostrategic importance shifting the economic center of gravity towards the Global South.

However, the BRICS do not limit their ambitions to an economic agenda, but rather seek to leverage their collective economic weight to pursue a wider political ambition. Believing that the progress of emerging and developing countries are hindered by a Western centric economic and political order, the BRICS have engaged in a number of actions to rebalance and counteract the existing global order alongside its institutions.

Notably in order to reduce dependence on the World Bank and International Monetary Fund -institutions that are historically led by Europeans and Americans and are often criticized for their lack of transparency and draconian structural adjustment programs – the BRICS established the New Development Bank in 2015 to mobilize resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects. With initial authorized capital of $100 billion, by 2022 the bank has assigned $32.8 billion to 96 approved projects, helping to build and upgrade 15,700 km of roads, 850 bridges, and 260 km of rail transit networks. Facilitating growth and development on more favorable terms, while simultaneously reducing dependence on Western-led institutions articulates a clear message about the shifting sands of global power.

From a diplomatic perspective the hosting of the annual BRICS summit allows the group to meet and discuss issues they believe are specifically important to emerging market economies. Symbolically, this sends a signal to the West, and particularly the G7 countries, that they no longer exclusively control the global agenda via membership of their exclusive economic and financial forums, which have historically favored their market-based economies and financial systems.

Indeed, although a number of the BRICS membership are keen to reform the international monetary system, and challenge the dominance of the US dollar, it is less clear how this will be achieved. While the creation of a common BRICS currency would in theory reduce vulnerability to dollar exchange fluctuations; the implementation of a BRICS currency is, at best, many years away given the lack of macroeconomic convergence widely considered to be critical to a successful common currency. Further rebuffing any prospect of dethroning the dollar, according to the Bank for International Settlements, the US Dollar remains the single-most traded currency, accounting for almost 90% of all foreign exchange transactions. Second, as the world’s reserve currency since 1944, the dollar accounts for 60% of global foreign exchange reserves whereas by comparison the Chinese renminbi accounts for 3%. Third, the dollar is easily convertible (liquid), widely accepted as a medium of exchange, and largely free from capital controls, of which the same cannot be said of the Chinese, Russian, Indian and South African currencies. In short, while the BRICS will likely increase their use of local currencies for bilateral trade, in part reducing their exposure to foreign exchange volatility, the demise of the US dollar and the introduction of a BRICS common currency is overstated.

Therefore, while enlargement has expanded the BRICS economic power and geostrategic reach, the BRICS face a number of domestic and geopolitical challenges, which will limit both deeper integration, and ultimately the group’s ability to shift the balance of global power in their favor.

First, while the collective might of the BRICS economies is beyond question, the groups leverage on the international stage is highly reliant on the $17.9 trillion Chinese economy, which accounts for 62.9% of the groups economic output. This dependency is problematic for a number of reasons, not least because it makes China disproportionately powerful within the group itself, but interrelated to this point is bilateral power dynamic between China and India. For example, although India has the second largest BRICS economy, China’s economy is five times larger in GDP terms; and while the BRICS may talk about ‘sovereign equality’ and ‘mutual respect,’ ultimately ‘money talks’ giving China greater leverage and scope to implement its world view and interpretation of any recalibrated global governance system.

Expanded BRICS GDP in trillions of USD; Source: World Bank

Yet, while China and India agree on a need to rebalance the distribution of global power better reflecting their elevated status, as competing economic superpowers and geostrategic rivals, bilateral relations are often strained. Rarely in agreement, heightened tensions around ongoing border disputes in the Himalayan region and India’s antipathy to China’s transcontinental Belt and Road Initiative are unlikely to result in consensus, yet if China and India cannot agree a common path, it is difficult to envisage how the wider BRICS grouping can ever achieve their full potential.

Second, with China forecast to have the largest global economy in both 2050 and 2075, recency bias clouds significant headwinds facing the Chinese economy. For instance, how Beijing’s political leadership chooses to address the harsh domestic realities of a slowing economy, soaring youth unemployment, an ageing and declining population, alongside the increasing potential for contagion in the overheated Chinese property market – a sector which accounts for 25% of China’s GDP – may all yet impact the global standing of the BRICS group.

Furthermore, economic uncertainty coupled with increased geopolitical tensions, particularly between China and the United States are leading companies to reduce their exposure to China, as demonstrated by a drastic fall in FDI from $189 billion year on year to $15 billion in 2023. Moreover, China’s direct investment liabilities appear to show that investors are rapidly repatriating profits and exiting the Chinese market. Whether this remains a long-term trend remains to be seen. However, with China facing considerable domestic challenges, investors are nervous, and this is before considering the consequences that may arise from any military conflict with Taiwan, an issue on which China is becoming increasingly assertive.

Indeed, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has laid bare the consequences of a major military conflict. While Russia has tarnished the BRICS reputation for promoting peace and security, one of its founding members and major economies is now ranked amongst the world’s riskiest countries in which to conduct international business. Not a good look, and one that was reinforced by a recent presidential decree allowing for the seizure of foreign owned companies and assets in Russia.

If Russia’s extraterritorial activities in Ukraine are causing an image problem, the BRICS brand, as a movement for the promotion of peace, security and stability is hardly enhanced via its recently expanded membership, of whom many have deep-seated and historical geopolitical rivalries. Iran, a regional power, is the group’s problem child. Economically unimportant but of geostrategic importance, Iran’s membership is highly controversial, in that Iran is considered by many to be the world’s largest state sponsor of terrorism regularly calling for the destruction of the United States and the eradication of Israel. Complicating matters further, Iran is currently engaged in a number of regional conflicts via its proxies and a decade long war against fellow BRICS member and regional rival Saudi Arabia in Yemen. As the only new member with a trillion dollar economy, Saudi Arabia, has also attracted criticism for its poor human rights record and extrajudicial killings, while on the African continent Egypt and Ethiopia are engaged in a stand-off over The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. If utilized in an unfriendly manner, the dam represents an existential threat to Egypt given 85% of Nile River water emanates upstream of the dam on Ethiopia’s Blue Nile.

In summary, the expanded BRICS are economically strong(er), yet geopolitically weak(er), and while they may rebalance the global order, any thoughts of replacing it are misguided. The eclectic mix of different political, economic, and cultural systems, including democracies, autocratic monarchies, authoritarian regimes, and an Islamic theocracy lay bare the difficulties associated with reaching a common ground on any new system of global governance. By contrast the Western dominated system they seek to counteract, while not perfect, is far more homogenous, founded on a well-established rule-based order, and without the scale of geopolitical tensions that engulf the newly expanded BRICS.

Will BRICS Expansion Finally End Western Economic and Geopolitical Dominance?

January 28th, 2024

January 28th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Monitor, an article on BRICS expansion and its potential impact on the West’s economic and geopolitical dominance:

This entry was posted on Sunday, January 28th, 2024 at 1:32 am and is filed under BRICS. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

ABOUT

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.