April 30th, 2023

Via Amwaj Media, commentary on the potential for Iran to generate transit revenues:

While all signs and indicators point to rapid economic deterioration in Iran, officials continue to speak of a positive outlook for the economy. Defending his government’s budget for the next Iranian year (beginning March. 21, 2023), President Ebrahim Raisi has presented an economic picture that seems detached from reality.

Addressing lawmakers on Jan. 22, Raisi spoke of 4% GDP growth, a 5% expansion in manufacturing, and the realization of his government’s plans in the field of employment. He is not alone in his apparent belief in these questionable projections. Deputy Foreign Minister for Economic Affairs Mehdi Safari believes that Iran is about to become a superpower.

The underlying bet

The sentiments expressed by figures such as Raisi and Safari raise the question of whether there is a tangible development that is generating the apparent optimism about the trajectory of the economy. An in-depth analysis of recent statements by various political figures points to the vision of future economic impetus fully relying on the consolidation of trade and economic ties with eastern powers, especially China and Russia.

Indeed, ever since Iran in Sept. 2022 became a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), officials have put a lot of emphasis on the associated economic dimensions. The argument is that de-dollarization of trade and the implementation of direct banking and payment channels between SCO member states will help compensate for the negative impact of western sanctions.

Politicians such as MP Ali Haddadi, the spokesman of the parliamentary internal affairs commission, believe that the economic impetus of SCO membership and potential inclusion in BRICS—the group of emerging economies Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, which Iran hopes to join—will be very significant. But international experts are not as convinced that these developments will boost Iran’s economic outlook.

Increased focus on transit

Putting aside the speculations on the dividends of joining various blocs, there is one sector that will clearly make a difference for Iran in terms of job creation and economic impact: the transit sector. Tehran has paid attention to the sector’s growth potential—a process that has been supported by geopolitical developments in neighboring regions.

The bigger picture features two parallel initiatives that should be taken into account.

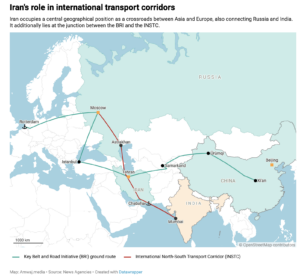

First, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been receiving major coverage in Iran as a development that will have positive impacts. Second, there is the emergence of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)—a multinational project to connect India with Europe and Central Asian markets via Iran and Russia.

Counterbalancing the BRI, Iran and India are among the INSTC’s founding member states. Yet, since signing the initial agreement on the project back in 2002—incidentally the same year that the Iranian nuclear crisis first erupted—western sanctions have hampered the realization of the Iranian segment of the transit network. This has been particularly evident in the slow progress of India’s efforts to develop the southeastern Iranian port of Chabahar, 70 km (43.5 miles) west of the Chinese-led expansion of the Pakistani port of Gwadar.

However, these dynamics seemingly are about to change. The simultaneous western sanctioning of Iran and Russia—the latter over the Russian Feb. 2022 invasion of Ukraine—has created an incentive to accelerate the needed investments by key stakeholders. In this vein, Tehran and Moscow have explicitly stressed their desire to fast-track the INSTC project through Russian investment in the Iranian transport sector.

The most important current driver of the INSTC is how post-sanctions Russia will route its trade with Asian countries, especially India. Against this backdrop, more and more reports and analyses are laying out the significance of Iran as a transit country. The authorities in Tehran realize their centrality on the India-Russia trade route, and considering that India’s imports from Russia quadrupled last year one can deduct the potential upside for Iran.

The Iranian government has stated that it is implementing projects in the fields of improving port capacity, rail and road infrastructure, smart transportation terminals and most importantly, modernizing the transportation fleet. Moreover, the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture (ICCIMA) has inaugurated a new TIR (Transports Internationaux Routiers or International Road Transport) center in the southern port city of Bandar Abbas to accelerate the processing of transit cargoes.

However, there is a clear need for further investment in transportation infrastructure.

Challenges ahead

The Raisi administration’s goal is to annually generate 20B USD in revenue from regional transit. First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber last year opined that “transit could generate more revenues than petroleum exports.” This is while in Dec. 2022, MP Mohammadreza Pour Ebrahimi—the head of the parliament’s economy commission—cited “preliminary expert estimates” as saying that the “implementation of those projects will increase the country’s income by 10B USD annually.”

But the reality is that revenues generated by the sector have so far been below 1B USD per year. To additionally grasp the scale of the challenge ahead, experts estimate that Iran’s future potential for the transit of goods could be 200M tons while the present volume is below 10M tons, with a declining trend in the past few years.

Despite the expansion of investment in logistical infrastructure in Iran, there is still a major shortage of transit wagons and road transit capacity. At present, 90% of transit through the country is conducted on the road, which is less efficient than rail transportation. Experts have no doubt that capacity growth will have to come from heavy investments in rail infrastructure, especially the acquisition of new cargo wagons.

In addition to investment, security and time are two other main obstacles to the development of the sector. Issues related to the time and cost of transit could be resolved through new investments, but in terms of security, Iran will depend on political-security developments in the region as well as its own domestic dynamics.

It is evident that the potential of Iran’s transit sector is huge due to geography and current geopolitical developments. In addition to Asia-Russia trade, Iran also offers a good alternative to Russia’s growing trade with Persian Gulf economies. But whether Tehran can translate this potential into a significant hard currency earning sector will depend on the needed investments and structural adjustments. For instance, transport companies already complain about red tape and lack of bureaucratic capacity in addition to actions and regulations of border security institutions which slow down the transit traffic.

One facilitator of further development of transit capacities is the fact that all necessary equipment and technologies can be provided by Iranian companies alongside Russian, Chinese and Indian enterprises. Not depending on western technologies will make the growth of the sector feasible if projects are managed and implemented efficiently.

An expansion of transit revenues will also confirm to Iran that its strategy to promote relations with immediate neighbors and eastern powers in response to western pressure is working. Indeed, the realization of the country’s transit potential carries a broader message: that geography and geopolitics can trump sanctions—a means that western governments have increasingly deployed without an understanding of its limits.

Focusing primarily on The New Seven Sisters - the largely state owned petroleum companies from the emerging world that have become key players in the oil & gas industry as identified by Carola Hoyos, Chief Energy Correspondent for The Financial Times - but spanning other nascent opportunities around the globe that may hold potential in the years ahead, Wildcats & Black Sheep is a place for the adventurous to contemplate & evaluate the emerging markets of tomorrow.